The third edition of the Generation triennial, Generation 2023 (until August 20, 2023), includes more than 50 young artists chosen from a pool of 1,004 proposals. Many of the artworks came about during the pandemic, when the world as we knew it had ended.

Upon entering, before you have the chance to focus on anything else, a video demands your attention.

On a vertically oriented, rectangular screen, a soundless procession of dozens of human faces rapidly replace each other. The slightly irregular pace yields an effect like a flipbook animation. Each face distorts – features stretch, skin texture changes or colours turn neon – before morphing into the next person.

Resurface your face

From Face: to put on a face, to remove a face (2022), by Juho LehiöPhoto: Stella Ojala/Amos Rex

This is Face: to put on a face, to remove a face, an installation by Juho Lehiö (born in 2000). It’s arranged as a makeup table, with a screen in place of the mirror. The makeup option still exists, but recent years have brought another possibility: in the online world, filters let you edit and remake your face.

For some people, that’s more real than their real-life visage. That was the case with one of Lehiö’s customers in his job as a makeup artist, which inspired this piece.

On the other side of the installation, you can sit in front of a similar screen fitted with a camera and try filters on your own face. Looking past Lehiö’s makeup station, another rectangular image beckons from the wall.

Layers that divulge

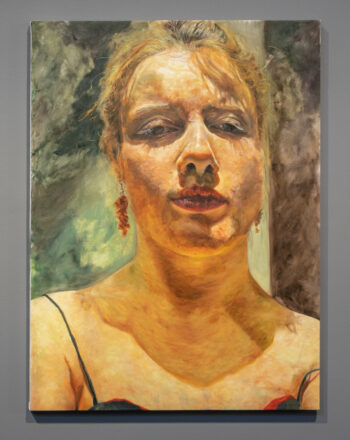

Self-portrait with makeup (2020), by Johanna SaikkonenPhoto: Stella Ojala/Amos Rex

Self-portrait with makeup, a large painting by Johanna Saikkonen (1998), is taller than it is wide. Her head and shoulders fill the frame; if this were a photo, you’d say it was close-cropped. We’re looking slightly upward at her – the angle is reminiscent of a video call.

From afar, the rich, multilayered texture led me to expect thickly applied paint, but when I came face-to-face with the image, that turned out not to be the case. What you do see is the texture of the underlying canvas, the surface of the subject’s skin and the makeup covering that skin.

You can see individual stray hairs and the shadows of those hairs on her forehead. The light is coming from somewhere above her, causing eyeshadow-like circles of shade around her eyes and a shadow from her chin to her collarbone.

Close up to the painting, it’s like being near enough to someone to see that they’re wearing makeup, so that it no longer makes their skin look smooth, but rather divulges that neither skin nor makeup is perfect. The layers of paint don’t correspond exactly to layers of makeup, but they convey the same effect. How’s that for a filter?

A multilayered take on makeup

From Filter (2022), by Juulia VanhataloPhoto: Stella Ojala/Amos Rex

In Filter, Juulia Vanhatalo (1999) films herself putting on makeup, but not the way you might think.

The three-minute video is projected onto the wall of a darkened side gallery. In the sequence, Vanhatalo is sitting in front of a wall, in the middle of a projection that shows the display of her own laptop.

She sits with her head and shoulders inside a white square that is a new, blank Photoshop picture. Using the program’s brushes, she superimposes “makeup” over her face, carefully applying colours for base, lipstick and eyeshadow.

In the video, the projection switches to show her phone screen as she opens Instagram and posts the new picture there. We see the makeup with no face behind it. Tapping the picture to enlarge it, she stands and moves into place, matching her features to the picture once again, like putting on a mask. Her eyes swivel before the video ends, gazing into the camera, looking at us.

The soundtrack during all this is the skittering, retro noise of a movie projector, as if to say, Nothing has changed. Or perhaps, Look how far we’ve come. Or maybe, We haven’t come very far. Or even, This is getting so old. We show the world a projection of a projection of a person in a painted mask, but the person and the mask exist separately.

Picking up the pieces

A fragment of Fragment collectors (2021–22), by Olivia ViitakangasPhoto: Stella Ojala/Amos Rex

Fragment collectors, by Olivia Viitakangas (1999), comprises seven framed photographs and a couple of display cases. It documents an imaginary profession: fragment collector (Viitakangas plays that role in the photos, while Liisa Hietanen appears as a trainee, a junior fragment collector).

The installation shows job interviews, contracts, authentic-looking ID badges, an office coffee room and the fruits of the labour: dozens of found glass shards, each in a tiny zip-lock bag and labelled with a number, a date, a colour, measurements, location coordinates and a description (“polygonal crumb, slated, scratched and bruised”).

It’s a tragicomic, deadpan send-up of working life, whether you take it literally or figuratively: worker ants gathering and cataloguing an endless supply of a specific subcategory of miniature garbage. Somebody made a mess, and someone else has to pick up the pieces of broken glass.

Fragment collector is such a great job title – you get the feeling it could really exist. It’s a nice touch that the display cases and photos are covered with panes of glass.

The end of something

The End (2022), by Amos BlomqvistPhoto: Stella Ojala/Amos Rex

The End, by Amos Blomqvist (2004), is a digital image, about 80 centimetres (31.5 inches) square, on a screen set into the wall. On a Helsinki metro platform, a display shows that a train will be arriving in one minute. The destination is given in Finnish and Swedish, which are both official languages in Finland: “Loppu / Ände” (End). The hands of an analogue clock say one minute before 12.

There’s just one thing: beyond the platform, where the track and tunnel should be, are clouds and blue sky, as if we’re looking out of an airplane. Viewers stop, waiting for something in the picture to move. People react differently to a glowing screen than they would to a print. We passively stare and expect something to change.

A man with a grey-flecked beard was looking at The End with his daughter, about ten years old, who was wearing a pink sweater. “It’s the end of the line,” he said. The girl asked, “Of what?”

“Exactly – what?” said the man.

“Is it the end of the world?”

“A world, yeah. Whose world? Or maybe just the train.”

“Is that real?” the girl asked.

“I don’t know,” the man said. “It looks real.”

By Peter Marten, June 2023