What’s the significance of a biennial? It offers locals and visitors new perspectives and insights, like any arts event, but it does so in a concentrated, festival format. Altogether, 29 artists and artists’ collectives from all over the world are on show at the second Helsinki Biennial.

Entitled New Directions May Emerge, it features 16 locations on scenic Vallisaari, an island just off the coast of the Finnish capital (until September 17, 2023). Additional artworks are on view at Helsinki Art Museum (until October 22) and several other places around the city. Some art is online or has online components.

Cultural events spill over and benefit businesses and society as a whole, too. “An interesting and attractive city cannot exist without a vibrant and distinctive cultural life,” Helsinki mayor Juhana Vartiainen told the press when the biennial opened. Arts and culture are “essential for…recruiting new talent and bringing business activity to the city.”

Tunnel visions

Tuula Närhinen’s The Plastic Horizon contains pieces of plastic that washed up on the shore. (For a closer look, see the slideshow below.)Photo: Peter Marten

The name Vallisaari (Embankment Island) refers to former military fortifications there, many of which date back to the 1800s. A number of the biennial’s exhibitions are located in spacious, tunnel-like chambers within those ramparts.

One of them, Finnish artist Tuula Närhinen’s The Plastic Horizon, consists of a low, narrow shelf loaded with pieces of plastic that she collected on the shores of Harakan saari (Magpie Island), where she has her studio, close to Helsinki. Scraps, fragments, candy wrappers, bottle tops, Covid masks and toys are arranged by colour along the shelf. The rainbow-like array attracts the eye from a distance, but becomes disgusting as you approach and realise that it’s a collection of trash.

Närhinen makes the point that this surprisingly large amount of plastic rubbish, collected on one tiny island, represents a minuscule fraction of total human pollution. Just as the colours hold a certain appeal for the artist’s audience, they also attract birds and marine life, which often die after ingesting the plastic.

Atmospheric records

Närhinen’s cyanotype prints show the white silhouettes of objects she found at low tide along the River Thames in London.Photo: Kirsi Halkola/Helsinki Biennial/Helsinki Art Museum

On the mainland, Helsinki Art Museum contains another of Närhinen’s installations, Deep Time Deposits, where she has hung sheets of paper in groups on two long walls. Each sheet is completely blue except for a scattering of white shapes. Accompanying shelves hold the objects that made those forms: shards of glass and pottery, seashells, jigsaw puzzle pieces, remnants of metal tools and nails, and other flotsam — even a crab claw.

The creative process included scouring the tidal flats of London’s River Thames, an activity called “mudlarking.” She found “very different objects” there than back home, she told me. “These objects are actually heavier. They’re buried in the mud, which then erodes when the river eats its way into the soil.”

For 34 days, she went mudlarking and used the debris she found to create cyanotypes – paper prints made with a photographic process that recorded the objects as white silhouettes on a deep blue background. The exhibition also displays all the bottles, trays, gloves and other equipment she used to complete the project, so we see not only the result, but how she achieved it.

The blue colour readily symbolises the aquatic environment, and the white shapes show what the artist has removed. She exposed the prints outside in the sun and rain, making them “an atmospheric record of the river’s ‘anthropogenic burden,’” as she says in the exhibition catalogue.

Reindeer, ice and embers

In Matti Aikio’s video Oikos, a turning wind turbine and a walking herd of reindeer are superimposed upon each other.Photo: Kirsi Halkola/Helsinki Biennial/Helsinki Art Museum

Back in another of Vallisaari’s tunnels, a video plays on a square screen. Long-lasting shots, sometimes overlapping to occupy the screen two at a time, show mist lifting from a mountain range, a herd of reindeer walking and grazing, half a dozen wind turbines turning, a snowmobile moving through the landscape, sunshine refracting into halos of light.

The name of the work, Oikos, an ancient Greek word for “family” or “household,” is the same word that gave rise to the prefix “eco” in both “ecology” and “economics.”

Near the end of the video, there’s a shot of what looks like pockets of air under the ice on the shore of a lake. Glowing, flaming campfire embers gradually appear; they also seem to be under the ice. Then the picture slowly fades to darkness.

The artist, Matti Aikio, filmed the footage of reindeer in an area where his ancestors herded reindeer more than 100 years ago. “My mother is Finnish and my father is Sámi,” he said, standing in the sunlight outside the gallery. The Sámi are the indigenous people whose homeland is divided into four parts by the borders of Finland, Sweden, Norway and Russia. His father’s village is Vuotso (Vuohčču in the Northern Sámi language), near Urho Kekkonen National Park in the far north of Finland.

The mountains in the video are in Norway and Finland, and the windmills are in Fosen, a region near Trondheim, Norway. (At the time of writing, a dispute about windfarms in that area was continuing long after a court had ruled that they interfere with Sámi reindeer herders’ rights.)

Images linger

Near the end of Aikio’s video, embers and fire appear behind a shot of bubbles under an ice surface.Photo: Kirsi Halkola/Helsinki Biennial/Helsinki Art Museum

“I wanted to use very long, lingering images and slow shifts, because one important aspect of the topics that I’m working with is also the relationship to time,” Aikio said. “The relationship to time is very connected to the relationship with nature. How do we relate to time as linear or cyclical or something else?”

He ventured, “Everything has to happen cyclically on this planet. That’s the only way to live inside the borders of the ecosystem.” That stands in contrast to the way much of the world runs today: societies consume resources without sufficient consideration for the future.

The conflict over windmills is one example of the complexity and ramifications of the climate crisis, to which “there is no easy answer,” said Aikio. “But the simple answer is that we just all need to slow down. We need to spend more time sleeping and thinking, and less time doing destructive things. We’d have time to think about the real consequences of our actions.”

One good way to slow down is to spend more time looking at art – maybe even on an island near Helsinki.

More views of the second Helsinki Biennial

Augmented reality and real life are blending together. Green Gold, an AR piece by Ahmed Al-Nawas and Minna Henriksson, shows timber transportation on the nearby waterway. Photo: Sonja Hyytiäinen/Helsinki Biennial/Helsinki Art Museum

Visitors to Vallisaari can enjoy sea views from an observation walkway above former military fortifications. Photo: Peter Marten

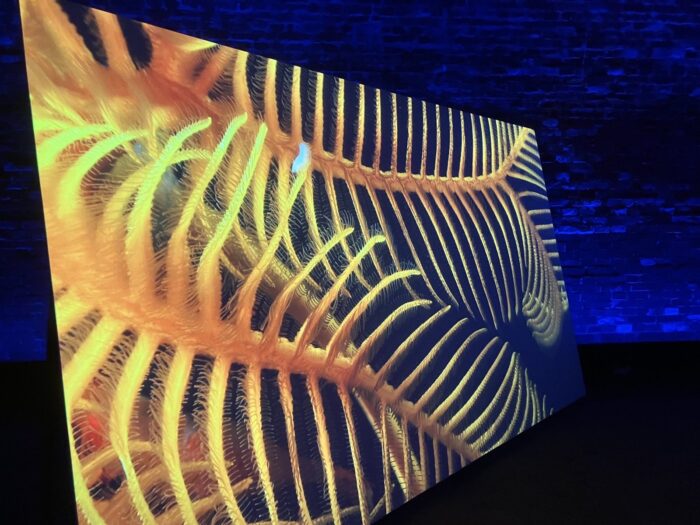

For her installation Hypoxia, Emilija Škarnulytė gathered footage from the depths of the sea. Photo: Peter Marten

¡Cuánto río allá arriba!, by Asunción Molinos Gordo, consists of pottery and implicitly asks if people should return to previous cooperation and solidarity around resources such as water. Photo: Peter Marten

Filmmaker Lotta Petronella, chef Sami Tallberg and musician Lau Nau created Materia Medica of Islands, which is part apothecary, part soundtrack and part tribute to Ilma Lindgren, who in 1914 stood up for the right to pick berries even on privately owned land. Photo: Peter Marten

Part of Materia Medica of Islands is a wall of moths stitched from red thread. Photo: Peter Marten

In Thou Shall Not Assume, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley presents characters online and as sculptures in a retelling of the stories of Black trans people. Photo: Peter Marten

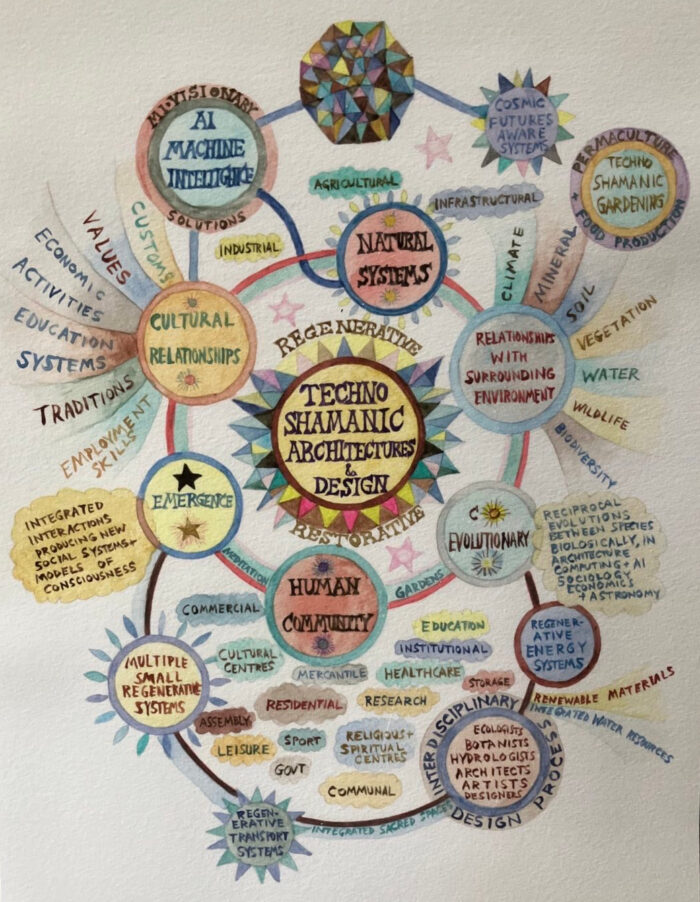

Suzanne Treister’s Technoshamanic Systems: New Cosmological Models for Survival consists of 185 exquisitely detailed watercolours, some with labels such as “Technoshamanic gardening,” “Regenerative transport systems” and “Cosmic futures aware systems.” Photo: Peter Marten

A toy boat is one of the pieces of plastic that landed on the shore of an island near Helsinki and became part of Tuula Närhinen’s The Plastic Horizon. Photo: Peter Marten

In Deep Time Deposits, Tuula Närhinen’s cyanotypes are accompanied by shelves that hold the objects she collected, and by the equipment she used to make the prints. Photo: Kirsi Halkola/Helsinki Biennial/Helsinki Art Museum

When you go to the island of Vallisaari for the Helsinki Biennial, you can also enjoy scenery, greenery and ocean views. Photo: Peter Marten

Sepideh Rahaa’s multichannel video installation Songs to Earth, Songs to Seeds visits rice farms in northern Iran and includes songs and stories from the labourers. Photo: Peter Marten

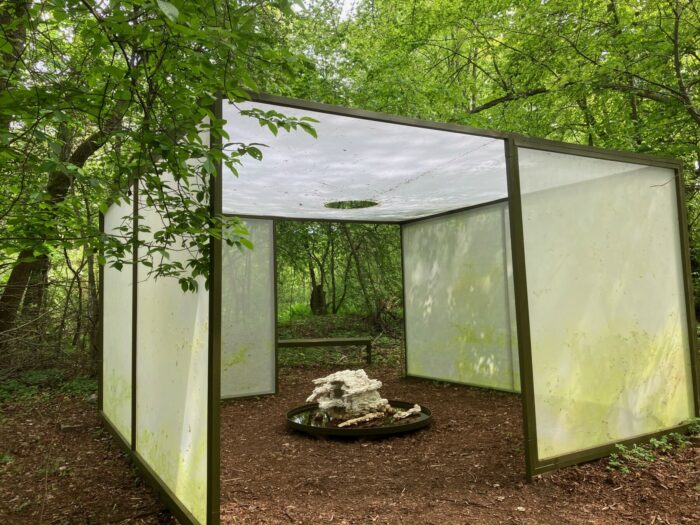

In Alma Heikkilä’s installation coadapted with, rainwater mixes with plant dyes and drips onto a sculpture, changing it over the course of the summer. Photo: Peter Marten

At Helsinki Art Museum, Bita Razavi’s Kratt: Diabolo No. 4 churns and rattles, looking like a cross between a spider and a printing press. Photo: Peter Marten

A cyclist rides past the Zheng Mahler collective’s Soilspace in downtown Helsinki. Photo: Peter Marten

By Peter Marten, August 2023