As Finland celebrated the 150th anniversary of Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s birth, we took a closer look at a great artist whose influence on Finnish society spans everything from pre-independence political paintings to modern-day tattoos.

One of the most renowned pieces of art to emerge from Finland is The Defence of the Sampo, by Akseli Gallen-Kallela (April 26, 1865–March 7, 1931). This vivid depiction of a pivotal scene from the Finnish national epic Kalevala is even more striking when you see it up close. Some people take this notion quite literally: One Finnish man has a replica of the painting tattooed across his back, a type of canvas that was considerably underutilised during Gallen-Kallela’s lifetime. “People now feel his art is so important that they want to put it on their skin forever,” says Tuija Wahlroos, director of the Gallen-Kallela Museum. “There is always a reason why they chose his work and what it means to them.”

Kalevala and beyond

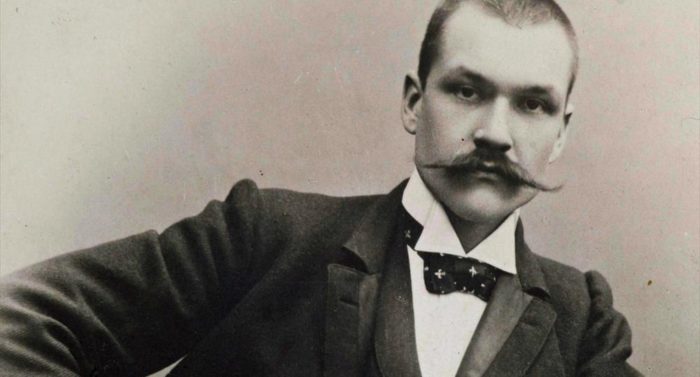

Not as stern as he looked: Gallen-Kallela shows off his hipster moustache in this 1890 studio portrait.Photo: Daniel Nyblin/Gallen-Kallela Museum

Such motives and motifs are revealed on July 4, 2015 at the museum, located in the artist’s former home just outside of Helsinki. In an event that seeks to expand people’s picture of the artist, photographs of people showing off tattoos inspired by Gallen-Kallela’s work will be accompanied by commentary. “His images are so well adapted to tattoos,” Wahlroos says. “They are very clear-lined and strong in many ways. This shows interestingly how Gallen-Kallela’s art transfers. I told this to a colleague who lives in the UK and he was so jealous that we have this kind of thing here.” Gallen-Kallela was greatly inspired by the Kalevala. He planned a richly illustrated version nicknamed the Great Kalevala, and completed illustrations for five of the 50 Kalevala “runes” before his death. The ceiling frescoes in the entry hall of the National Museum in Helsinki form another example of his passion for the national epic. Nonetheless, the Kalevala was just one of many interests for an artist whose legacy remains hugely influential in the Finnish art world. Gallen-Kallela was adept in artistic fields, including architecture, and championed graphic design in Finland. He also created the first example of modern Finnish design at the Paris World Fair in 1900 with Liekki (Flame), a rug artwork woven using the traditional ryijy technique.

Work ethic and family life

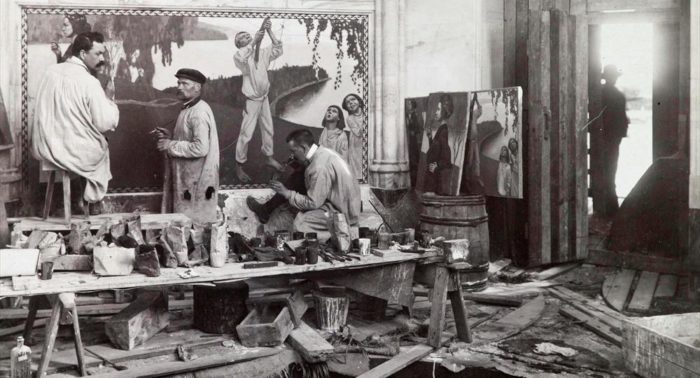

In this 1902 photo, Akseli Gallen-Kallela (left) and assistants are painting the fresco “Spring” in the Jusélius Mausoleum in the west-coast town of Pori.Photo: Gallen-Kallela Museum

Photographs suggest that the artist was a stern gentleman, surrounded by privilege – a misperception that Wahlroos is keen to dispel. “The picture of Gallen-Kallela has become too stuffy,” she explains. “In his time he was hardworking and lived a not-so-luxurious life that was rich in many other ways. He was normal father and had the same kinds of problems as everyone else.” History has also painted Gallen-Kallela as a frequent socialiser. Parties with the likes of famed composer Jean Sibelius (also born in 1865) have become folklore. While the artist certainly enjoyed socialising on occasion, such gatherings took place in the midst of great artistic productivity. “He had a very high work ethic,” Wahlroos says. “If you think about his vast life’s work, thousands of paintings and other artworks, it is obvious he couldn’t have done all this if he was frequenting bars or restaurants all the time. On the contrary, he enjoyed family life.”

Independent spirit

The artist built a studio and house, complete with a castle-like tower, by the sea at Tarvaspää, just outside Helsinki. It is now the Gallen-Kallela Museum.Photo: Helinä Kuusela/Lehtikuva

Testament to his diverse interests, many of these artworks and personal items are on display at the Gallen-Kallela museum. His 1906 painting The Royal Ship of Free Finland, on loan from the Reitz Foundation, depicts the most pressing cultural issue of the era: Finnish independence. Like many of his contemporaries, Gallen-Kallela commented on the brewing discontent with Russian rule through his work. His societal impact became even more prominent after independence was achieved in 1917; he was named as General C.G.E. Mannerheim’s adjutant in 1919. Over the course of a year he created numerous symbols of independence, including a proposed design (eventually rejected) for the Finnish flag. Perhaps his most notable work was designing the medals that make up the Order of the White Rose of Finland, a system still in use today for honouring military and civilian merit. The artist’s spirit lives on, both in Finland and abroad. “Gallen-Kallela had a wide international network,” Wahlroos says. “In our archive we have the letters he received, from more than 2,000 people all over the world.”

By James O’Sullivan, April 2015