Finland, Sweden, Russia, Canada. Fisticuffs, war, excitement, near-death experiences, long journeys. No, we’re not talking about ice hockey. We’re reading the memoir of a Finnish Canadian.

Rauni Ollikainen’s self-published, cleverly titled book Finnish Beginnings opens with screaming. As she is born in a Helsinki hospital, bombs are falling outside, part of the Second World War. She spends her first hours alive in an underground shelter.

Told from a little girl’s perspective informed by the insight and hindsight of an adult, Ollikainen’s story forms an exciting and touching story that overlaps with major events in Finnish history. It also makes you want to know what happened next, after the book finishes – more about that below.

She draws readers in with details of everyday life in post-war Finland, and opens a first-person window on the gritty immigrant experience. Ollikainen, her parents and her two sisters left Finland for a new start in British Columbia, Canada when she was eight years old.

Why did they leave? Whom did they leave behind? How did they adjust to their new country? These questions remain captivating more than six decades later, and they also make for a great story.

Memories of memories

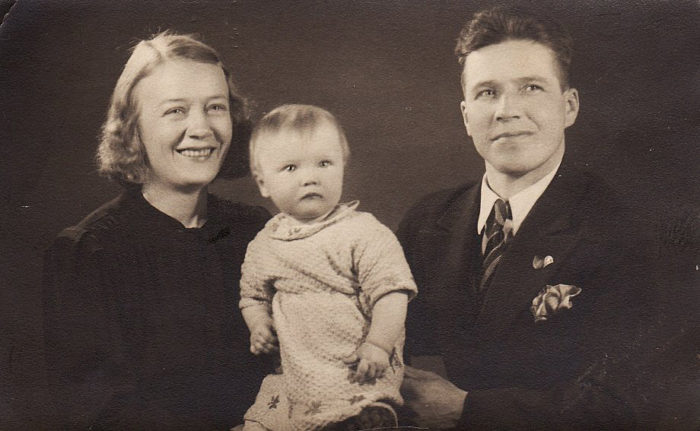

Rauni Ollikainen’s parents Taimi (left) and Sulo show off their first-born daughter Pirkko.Photo courtesy of Rauni Ollikainen

“Sometimes memories are just memories of memories,” Ollikainen says early in the book. Some of her first memories come from a voyage to Sweden at the age of 18 months. Nearly 70,000 Finnish kids lived with host families in Sweden to escape the dangers of war. Ollikainen returned two years later to a family and a language she barely recognised.

Her family lived in a two-room Helsinki apartment with her grandmother. When she was five they moved to a house in the country. Several years later they emigrated.

Before that, she and her younger sister each had a brush with death. (We won’t spoil the story, though.) Ollikainen also overheard the grown-ups discussing life and politics often enough to be able to fill in the reasons that led her family and many others to emigrate.

No more war

Winter camouflage: Finnish ski troops such as these fought on the eastern front during the Winter War.Photo: SA-kuva

During her childhood, war remained fresh in people’s minds – the Second World War (which Finnish historians divide into the Winter War of 1939–40, the Continuation War of 1941–44 and the Lapland War of 1944–45) and the short but brutal Finnish Civil War of 1918, just months after Finland’s declaration of independence from Russia.

She remembers her father’s Winter War stories. He didn’t hate Russians, but he hated Stalin and he hated having to kill people, Ollikainen writes. “Couldn’t you just make a deal with every Russian you came across and tell them that you wouldn’t kill them if they wouldn’t kill you?” she asked her dad as a little girl.

“It doesn’t work that way,” he answered. He added, “Maybe little girls should run the world.”

For a reader living in modern Finland, Ollikainen’s accounts of war and Finnish politics seem to draw upon various versions of Finnish history: the history-book version that tries for an impartial account; the version she observed and heard about as a small child; and other, possibly nostalgia-laden, versions from oral and written sources.

From Finland to Vancouver Island

Helsinkians clean up rubble after a bomb attack during the Second World War. Memories of war played a role in the Ollikainens’ decision to emigrate.Photo: SA-kuva

Post-war Finland was wary of new conflicts in Russian-Finnish relations. Ollikainen’s parents decided to move to Canada, where they would never have to experience war again.

In detailing the bittersweet period before they left, she shows how various friends and relatives encouraged or discouraged her parents’ heartrending decision. Her grandmother chose to stay in Finland.

The family ends up on the west coast of Canada. Triumphs and setbacks follow: Ollikainen helps her father find his first job in Canada when she overhears some Finns talking about needing another worker to participate in building a dam up north.

They eventually establish themselves in their new country and discover vibrant Finnish communities in Vancouver and on Vancouver Island.

What happens next?

Rauni’s mother Taimi holds her hand as she takes some of her first steps in a Helsinki park. Photo courtesy of Rauni Ollikainen

The book ends when Rauni Ollikainen is a teenager. After such an absorbing story, we immediately wanted to know what happens next. So we contacted her and asked.

“So many people ask me if I’m going to write a volume two,” Ollikainen says. “It’s a possibility.”

What happened to her parents? “My mother passed away 15 years after we moved to Canada,” she says, “and my father remarried, to a Finnish woman from Finland, and moved back.”

Did Ollikainen ever live in Finland again? Yes, about 25 years after leaving: “I lived and worked in Finland for almost a year.” Her son was 12 at the time. “His Finnish schoolmates were so proud that they had a real Canadian on their hockey team. As an adult, he is still interested in all things Finnish.”

Can she still speak Finnish? “[When I went back to Finland,] I stumbled a bit at first, but was surprised how quickly it came back. Of course, now that many Finns are joining my Finnish Beginnings Facebook page, I am having conversations in Finnish with Finns from Finland and all over the US and Canada. ”

“I’ve had many Finnish Canadians contact me, people who knew my parents and Finns who have heard about my memoir. As far as my grandkids and nieces and nephews – some are interested, some are not. But the book will be in the family, so when they are older, they might get interested in their roots and their Finnish heritage.”

By Peter Marten, March 2014