The northern reaches of the Bay of Bothnia, the part of the Baltic that stretches between Finland and Sweden, are especially prone to becoming blocked by ice, but it often occurs in more southerly transport corridors as well. The “fast ice” – the ice that occurs closest to the shore – can measure up to 70 or 80 centimetres (28 to 32 inches) thick in the north, while ice fragmented by gales can build up into formidable ridges that are 25 metres (82 feet) high.

Assistance might be needed at any Finnish port, from Kotka and Helsinki in the south to Raahe, Oulu and Kemi further north, for the cargo ships that provide crucial import and export links to keep the Finnish economy running through the winter.

The task of clearing the ice “fairways,” or sea routes, falls to the state-owned company Arctia and its eight icebreakers, including the newest, state-of-the-art addition, the Polaris. Freeing ships from the ice can involve subtle, skilful manoeuvres and know-how, not only sheer power.

In the slideshow below, we set sail on the icebreaker Otso and follow its ten-day shift, working day and night to keep the fairways open for the ports of Oulu, Kemi and Tornio.

The other six are called Voima, Urho, Sisu, Kontio, Nordica and Fennica. You can see the vessels parked on the quayside for maintenance in the summer beside Helsinki’s Katajanokka district.

On assignment with the icebreakers

The icebreaker Otso prepares for its duty voyage from the port of Oulu on the northern Baltic Sea. Photo: Tim Bird

The view from the bridge of the Otso as it embarks on its ten-day shift to keep the fairways open through the coastal ice. Photo: Tim Bird

Temperatures can drop below minus 30 degrees Celsius (minus 22 Fahrenheit) on the Bay of Bothnia, but it doesn’t need to be that cold for ice cover to form in the brackish Baltic. Photo: Tim Bird

Second officer Arvo Kovanen and captain Teemu Alstela plan their next “assist” from the bridge of the Otso. Photo: Tim Bird

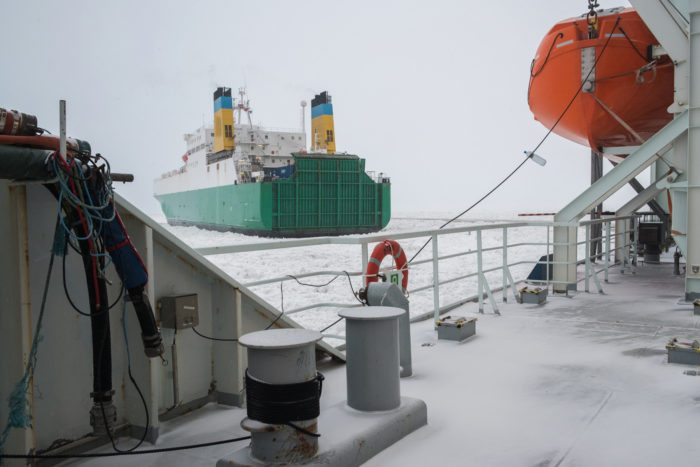

Cargo ships depart from Finnish ports loaded with paper and other forest products. Freighters of any size sometimes need freeing from ice traps. Photo: Tim Bird

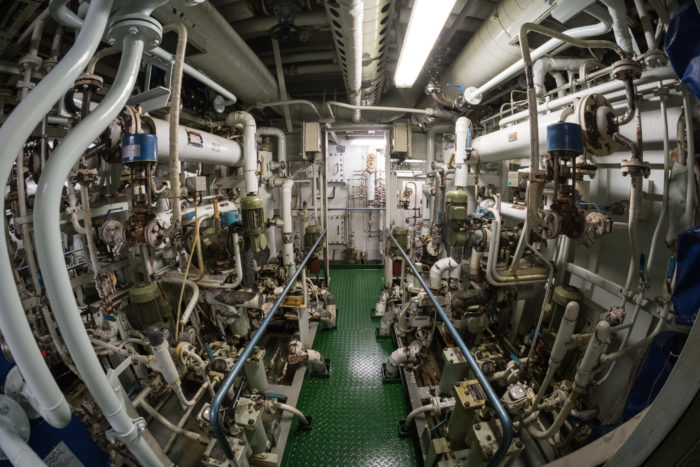

A section of the Otso’s engine room. The ship has four diesel engines made by the Finnish company Wärtsilä and includes an air bubbler system in its bow. Photo: Tim Bird

The icebreaker Polaris on its first assist voyage, leading a cargo ship into Tornio harbour. The Polaris features the world’s leading icebreaking technology. Photo: Tim Bird

A freighter heads out to open sea as an eerie mist accumulates over the frozen Baltic. Photo: Tim Bird

In the midst of a gale-force blizzard, the Otso approaches a freighter, preparing to tow it as it encounters immense pressure built up in the fragmented ice. Photo: Tim Bird

A Dutch freighter approaches the V-shaped bay at the stern of the Otso, ready to be towed through the fairway. Photo: Tim Bird

Having escorted a freighter out to open sea, the Otso turns back dramatically towards the ice that the wind has piled into deep ridges. Photo: Tim Bird

As ships approach port, pilots clamber on board from high-powered launches to guide the passage into and out of the harbour. Photo: Tim Bird

Icebreakers are immensely powerful, but the Otso slows to just four knots to approach this freighter. Freeing ships from the ice can involve subtle, skilful manoeuvres and know-how, not only sheer power. Photo: Tim Bird

By Tim Bird, February 2017