To slow the spread of the Covid-19 virus, the Finnish government decided that schools and universities should shut their doors in mid-March 2020. But the academic year didn’t end. And months later, when the following school year began, kids, parents, teachers and administrators were prepared for a situation that could change quickly.

In March 2020, Finnish teachers accomplished the incredible task of moving their classrooms online, many within just a few days. This situation continued until mid-May, and for some schools and certain age groups until the school year finished at the end of May. Whether in physical or digital classrooms, school remains an important part of life.

As we are updating this article, in mid-August 2020, the 2020–21 academic year is getting under way, and the Ministry of Education has stated that schooling will principally take place in physical classrooms, although schools of all levels will maintain flexibility to switch to solutions such as distance learning if the situation changes. Regional variations in the coronavirus situation may mean that different municipalities enact different measures to follow the guidelines of the ministry and of the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare.

In April 2020, we visited a family and talked with teachers to see how distance learning was taking place in Finland. (All ages and school years mentioned here are correct as of that time.)

Third-grader Isabel, 10, continues to follow her usual lesson plan. School begins at 9 am sharp and ends at 1 pm, just like it normally would. Her teacher keeps to the lesson plan, uploading daily instructions on an app called Qridi, which Isabel accesses on her phone. She reads the instructions and gets to work.

First up today is geography: “Read pages 118–121 about Denmark and complete the questions in your workbook. Take a picture of your answers and upload it to your diary.”

Online classroom

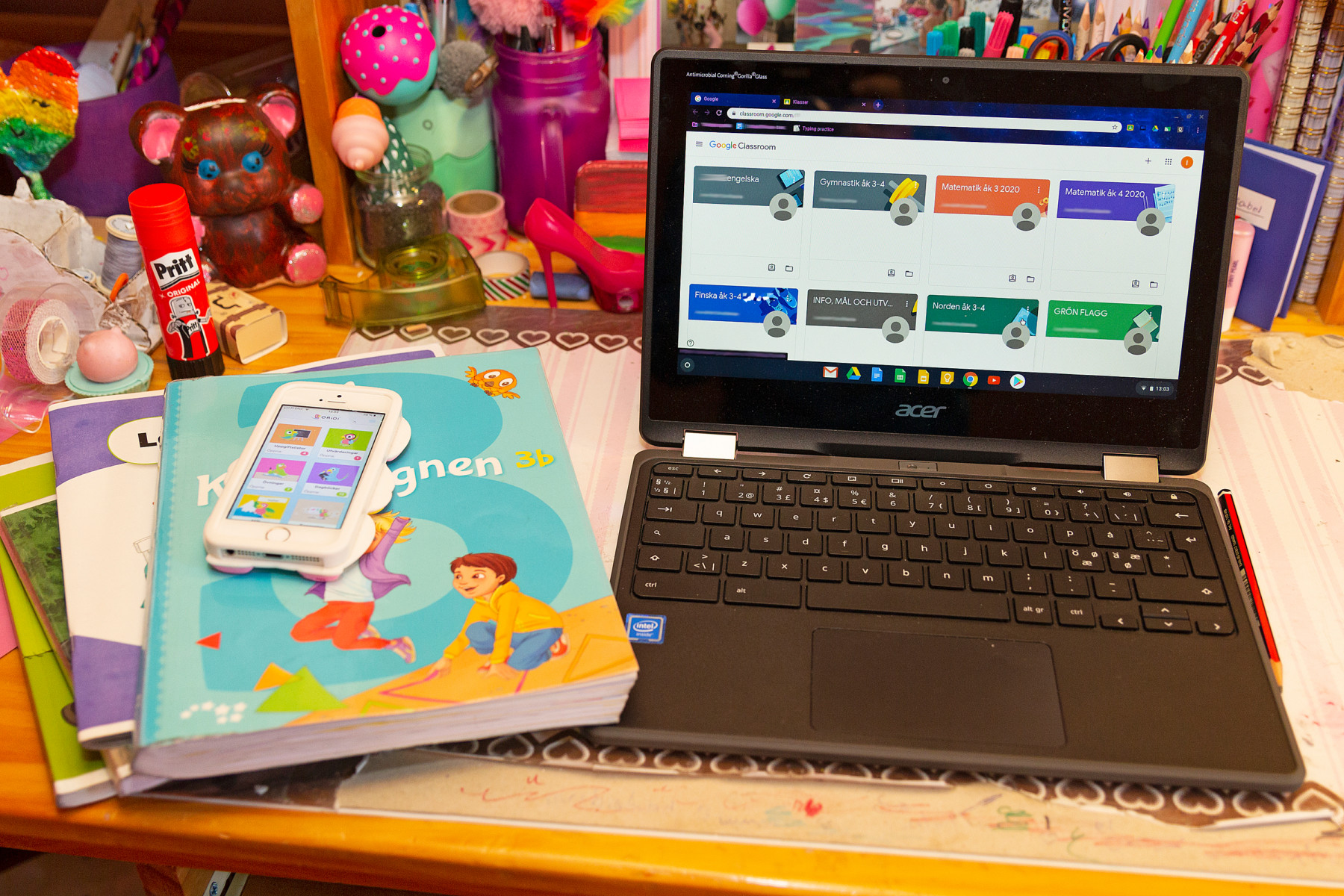

Between phone, laptop and actual, in-real-life schoolbooks, students are able to communicate with their teachers and keep up with their lessons. Photo: Catarina Stewen

At 9:30, it’s time for the day’s online meeting using Google Meet. Isabel logs on to Google Classroom on a tablet borrowed from her school. The screen lights up with the faces of all her friends.

The teacher asks them to mute their microphones and listen to her instructions. A “thumbs up” sign takes the place of a raised hand when a student wants to ask a question. They need to take turns, exactly as they would in a conventional class situation.

Teachers in Finland know that without breaks for exercise and movement, kids won’t be able to concentrate on their schoolwork. Usually this happens during 15-minute outdoor recesses at regular intervals throughout the day. Many experts believe that this plays a part in the Finnish education system’s success.

Today Isabel’s teacher includes a link to a dance-along video in the daily instructions, for the students to watch on their own. In addition to getting them moving and having fun, the song helps them practise English vocabulary and the maths concept of patterns.

Listening to lectures from a distance

We’re willing to bet that you won’t find a chair like this in any university lecture hall in any country.Photo: Catarina Stewen

Meanwhile, Isabel’s older brother Joakim logs on to his university’s online channel, tuning in for a lecture about software development. Åbo Akademi University, located in the southwestern Finnish city of Turku, has used web-based lectures regularly during the year, so the change is not that huge.

“Language classes have not been virtual until now,” he says. “The teacher uses Zoom to divide us into smaller groups for discussions, and visits each group to follow what we’re talking about, which works really well.”

Tech-savvy teachers

And now for a brief intermission: Get up and move around! Teachers in Finland know that kids need recess and exercise, even during distance learning. One teacher recommended this American-produced video as a study break; it also helps with English and maths.

Video: GoNoodle

Transferring classes to an online environment overnight is not a simple task. Teachers have been working tirelessly to familiarise themselves with digital tools, learn new features and set them up.

“Luckily technology is widely used in normal teaching, which means that many programs and platforms are familiar to both students and teachers,” says one upper secondary school teacher in the eastern Finnish city of Joensuu.

“There are also many fun scholastic exercises you can find online, free of charge,” says Anders Johansson, who teaches math and science at Källhagen School in Lohja, a town about 50 kilometres (30 miles) west of Helsinki.

Many schools have IT support, and teachers compare notes and share experiences. For younger students, schools have called upon parents to assist in getting things up and running. Teachers are using various apps and tools for online teaching, including Qridi; Classroom, Meet and Duo by Google; Teams by Microsoft; Zoom; and WhatsApp.

The question of internet access

With a phone balanced on the music stand, instrument lessons have also moved online.Photo: Catarina Stewen

According to Statistics Finland, most Finnish homes have access to the internet and nearly all school-age children have mobile phones.

Younger students without their own smartphones have been able to borrow one or receive instructions on their parents’ phones.

Students still need paper and pencil: Schoolbooks, distributed earlier in the year, are used for daily schoolwork, even though instructions arrive by phone or are available online.

However, there are families without internet access, or those who speak other languages at home than the official languages Finnish and Swedish. This can complicate the process of accessing online solutions. “In some cases we have invited the family to school for practical instruction,” says Johanna Järvinen, principal of Ilpoinen School in Turku.

Schools can lend tablets or laptops normally reserved for classroom work to students for distance learning. The Finnish National Agency for Education, in cooperation with the business community, is also gathering used laptops for students who lack access to a computer.

Extended hours

In an otherwise empty classroom in Helsinki, fourth-grade teacher Elina Heinonen teaches her students in distance learning sessions.Photo: Vesa Moilanen/Lehtikuva

Under the exceptional circumstances, normal working hours have not been sufficient for teachers.

“Planning, giving instructions and evaluating each student’s work takes much more time than in a normal class setting,” says Maria Kotilainen of Kyrkoby School in Vantaa, just north of Helsinki.

“Teachers have had to learn many new things in a very short period of time,” says Marica Strömberg, who works at Solbrinken School in Lohja. Another area of concern for teachers is the subset of students who, even under normal conditions, need extra learning support.

Keeping learning flowing

In Parliament on April 2, 2020, Minister of Education Li Andersson (second from right) answers a question about distance learning. Also shown are Katri Kulmuni (left, Minister of Finance at the time), Minister of Justice Anna-Maja Henriksson, and Minister of Employment Tuula Haatainen (right).Photo: Markku Ulander/Lehtikuva

Classes continue to follow the Finnish national curriculum, although the government has advised that teachers may lower the bar for achievement during this unusual time. Teachers, students and parents should not demand perfection of themselves, especially under these circumstances.

Minister of Education Li Andersson clarified in a press conference in early April that teachers are still responsible for verifying that kids are participating in their lessons, just as they would take attendance in a normal classroom. Andersson said that teachers should maintain channels of communication with the students and their homes.

The guarantee of high-quality education for all schoolchildren remains in effect. Whether online or brick-and-mortar, school attendance plays an important role in daily routines and in giving students a sense of security.

“Our target is to keep up with the schoolwork and continue to learn, just as usual,” says Ann-Britt Sandbacka, an elementary school teacher at Kyrkoby School.

By Catarina Stewen, April 2020, updated August 2020