Finnish Estonian writer Sofi Oksanen talks with us about her bestselling novel Purge. The first book ever to win both the Runeberg Prize and the Finlandia Prize, it also took the Nordic Council Literature Prize. By the end of 2012, four years after publication in Finnish, Purge had been translated into 38 languages.

Sofi Oksanen’s Puhdistus (Purge) topped the Finnish bestseller list in 2008 and won the prestigious Finlandia Prize, as well as several others. In February 2009 it went on to receive Finland’s other big literary award, the Runeberg Prize, named after the country’s national poet J.L. Runeberg (1804–1877).

Purge has the honour of becoming the first book ever to win both the Runeberg and the Finlandia, and Oksanen swept the board by winning the 47,000-euro Nordic Council Literature Prize as well, in March 2010. The English translation appeared in mid-2010.

In April 2013, Oksanen was awarded the Swedish Academy’s 42,000-euro Nordic Literature Prize.

The real Soviet Estonia

Oksanen may be the only person in a position to write a book like Purge. Born in 1977, the Finnish Estonian author grew up in Jyväskylä, central Finland and spent her summers in Estonia – not in the capital Tallinn, where tourists were not unusual, but out in the country. Her grandmother lived on a kolkhoz, a Soviet collective farm, so going to see her meant visiting an area where no Westerners were actually allowed.

Thus Oksanen saw what Westerners weren’t supposed to see – “the real Soviet Estonia”, as she calls it. She is close enough to that world to have street credibility, but distant enough to perceive the bigger picture.

The novel flips back and forth between past and present, following Estonia from before the Stalinist deportations of 1949 until after independence in 1991. “It’s almost impossible for me to write chronologically,” says Oksanen. “I try to link things on a metaphorical or symbolic level, or just by intuition.”

The book also alternates between the main characters, two women from different generations: Aliide, a rural villager, and Zara, a victim of human trafficking. Both experience extreme violence and try to survive their lives in worlds that offer limited options, and where sanity often seems scarce.

Musicality, pace and pain

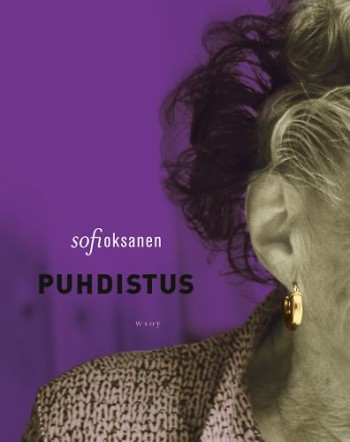

“For the cover I wanted a big ear and a golden earring,” says Oksanen. Photo: R. Eiro; art: S. Sorsa

Purge appeared as a play before Oksanen wrote the novel, and she garners recognition from reviewers for her ability to build a plot full of suspense and drama. She writes prose that flows naturally, showing events in vivid detail.

Somehow you know what she means when she describes a kitchen as “mute and screaming”, or when Aliide thinks of herself and another character as “safe and together” when in fact they are neither. “My intention is to write in a musical way,” says Oksanen.

She changes gears at will, increasing the pace over the course of a sentence to keep up with characters as their minds race. Her style is warm enough to let the reader into their thoughts at their darkest, most painful moments. We experience their despair as they weather betrayal, violence, rape, injustice and fear, yet Oksanen never makes the reader feel like putting the book down.

Going to Siberia

The Finnish word puhdistus can mean “purge”, but it comes from the word for “clean” and can also be translated as “cleansing”. It denotes the deportation to Siberia of tens of thousands of Estonians under Stalin.

“When I was a child,” says Oksanen, “no one talked about deportations. People ‘went to Siberia’. Certain things were so dangerous to mention that people used a lot of expressions to circumvent the actual issues.”

“When I started the play and was thinking about the title, I was thinking about the traumatic reaction people can have after they’ve experienced violence or been raped,” she says. “People always try to clean themselves. So that was the first meaning – cleansing.”

Audience watching

Is it easier to write a novel after creating the story as a play? “A novel requires more background information,” Oksanen says. “You have to know a lot of things that you don’t need when you’re staging a play.

“I wanted to make the atmosphere and the world realistic in the novel. You don’t have to put the names of magazines and things like that into a script, because on stage the audience can’t see them.”

Telling the story in two different forms even alters the characters: “Even though I knew that Aliide was the type of person who would keep quiet, who wouldn’t talk things out or say them to Zara, in a play you have an audience. So in the play Aliide speaks more about what has happened. That’s a big difference.”

Strange incidents

Oksanen has her sights set on her next two novels. Photo: Toni Härkönen

When a Finnish Estonian author writes a book that digs into recent Estonian history, you have to wonder about parallels with Finland. Of course Finland never formed part of the Soviet Union, but “there are a lot of strange incidents in Finnish history related to the Soviet Union,” notes Oksanen. Certain films were censored for political reasons in the 1970s, and part of Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago was published in Finnish in Sweden because no publisher in Finland dared to touch it.

Are any of the incidents worth writing a book about? “I think so,” she says. “How ‘Finlandisation’ affected the press is a big issue, and how it affected Finnish schoolbooks.” For now, however, Oksanen has her sights set on her next two novels. Both will deal with Estonia; she won’t reveal any more than that.

Just days before her Runeberg win was announced, she told us, “Winning both Runeberg and Finlandia would be quite unique. Finlandia is only for novels, while Runeberg includes all genres, which means a much greater variety of rivals.”

Topping it all off by winning the Nordic Council Literature Prize makes Purge even more unique, and the rivals came from six different countries this time. “It’s difficult for me to see the novel as exceptional,” Oksanen told Finland’s largest daily, Helsingin Sanomat, after Purge was selected over competitors from Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Norway, Iceland and the Faroe Islands.

“Lots of readers from outside of Finland have said that the novel remains in their dreams for weeks,” she continued. “The feeling stays with you.”

By Peter Marten, February 2009; updated April 2013