Started in 2019 by the Children and Youth Foundation, the annual Read Hour Literacy Campaign has spread from Finland to Sweden, Estonia, the UK and Iceland.

The idea is simple: get as many people as possible, especially young people, to read for an hour on UN International Literacy Day, September 8, whether it’s a book, a magazine or even a comic book. Even if people read separately, reading brings them together by introducing them to new thoughts and cultures, encouraging empathy and ultimately showing them that people everywhere have many things in common.

For Read Hour 2021, an exceptional, multilingual Moomin story reading took place in the Icelandic capital at the Reykjavík International Literary Festival.

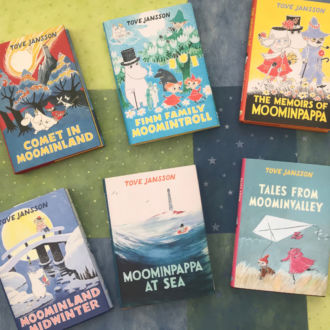

The Moomins, creatures created by Finnish author and artist Tove Jansson (1914–2001), are as popular in Iceland as they are in numerous other countries around the world. She wrote the books in Swedish starting in the 1940s (Finnish and Swedish are both official languages in Finland), and they have now been translated into at least 50 languages.

At Nordic House, a cultural centre in Reykjavík, Icelandic poet and author Gerður Kristný interviewed Sophia Jansson, Tove’s niece. Then Jansson and a panel of other guests read several pages each from the Moomin story “The Invisible Child” in their own languages: Swedish, Icelandic, English, Danish, Norwegian, Faroese and Finnish.

A good storm

At Nordic House in the Icelandic capital, Gerður Kristný (left) interviewed Sophia Jansson, Tove Jansson’s niece, before they and a panel of other guests read a Moomin story aloud in seven different languages.Photo: Alexander Schwarz

It is well known that Tove Jansson loved a good storm, and the Moomin adventures include catastrophic forces of nature such as floods, volcanoes and comets. “I think that for Icelandic people the Moomin books must be very real, in a way, because you live in the middle of enormous natural events,” Sophia Jansson told Kristný at Nordic House. Iceland has notoriously variable weather, and a volcano near Reykjavík decided to become active in early 2021, although it hasn’t threatened anyone’s life. (It has actually attracted quite a few curious tourists.)

“Tove used natural phenomena such as volcanic eruptions and floods as a counterweight to the safety of the Moomin House, Moominvalley and the Moomin family,” said Jansson. “Perhaps she felt that the magic is somewhere between those two extremes – danger and safety.”

These and other Moomin themes remain relevant in the modern world. “Many of the things in her books are things that you can still recognise today, if we consider all the refugees that were recently forced to leave Afghanistan, or other war-torn areas earlier,” said Jansson. “That’s a phenomenon that hasn’t disappeared – it was around after the Second World War when Tove was writing her books. The attitude that Tove wanted to convey was that if there are people who are fleeing and need safety and warmth, you have to receive them. You have to be open, tolerant and helpful.”

Individual and equal

If you’ve seen other buildings by Finnish architect and designer Alvar Aalto, you can immediately recognise his style in the shape, the white façade and the wood highlights of Nordic House, which opened in Reykjavík in 1968.Photo: Peter Marten

Sophia Jansson works in Helsinki as artistic director at Moomin Characters Ltd, the company that decides which product manufacturers may use the Moomin figures and artwork. “It’s unbelievable,” she said, “to have been given the gift of this role where I get to speak about an author who still means so much to so many people many years after her death, and who had values that you can support.”

Jansson remembers her aunt as someone who was “unique in many ways” and “amazingly gifted.” Not only did she write and illustrate books, but she was also a painter, a cartoonist, a theatre set designer and a songwriter. She also loved to dance and play the accordion.

“For me, her most beloved quality was the way she encountered other people,” said Jansson. “She possessed quite a rare ability to meet every single person as an individual and an equal. She never put herself above or below anyone else. She always showed that she was enormously interested in you, no matter who you were. That’s something I’ve tried to copy.”

And then what happened?

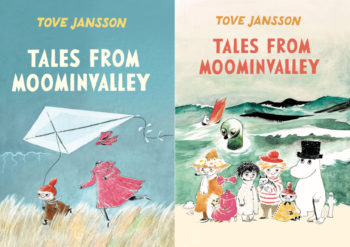

Different releases of the Moomin books have had various cover designs. These two recent editions of Tales from Moominvalley use vintage cover art; the one on the left shows Little My and Ninny, the invisible child, whose clothes can be seen.Photos: Sort of Books; cover art: Tove Jansson

After Jansson’s interview, she read several pages of “The Invisible Child,” a short story from the book Tales from Moominvalley, in the original Swedish. Kristný continued in Icelandic, then came segments in English, Danish, Norwegian, Faroese and Finnish, each read by a native speaker of that language.

The story is not as long or famous as the books Comet in Moominland or Moominsummer Madness, but it displays many of the values that Sophia Jansson appreciates in her aunt’s personality and work.

In “The Invisible Child,” a little girl called Ninny arrives at the Moomin family’s house. She had previously been in the care of a disagreeable woman who disparaged and belittled her until Ninny became invisible and stopped speaking.

The Moomins take her in, and gradually Ninny begins to reappear, and starts talking again, too. Her face remains invisible until the surprise ending, but you’ll have to read the story – or listen to Sophia Jansson read it in English – to find out what happens.

Epilogue

In March 2021, a volcano erupted at Fagradalsfjall, about 30 kilometres (20 miles) from Reykjavík as the crow flies. It has continued at irregular intervals, and has even become something of a tourist attraction.Photo: Jeremie Richard/AFP/Lehtikuva

When the reading was over and the audience had dispersed, a few of the participants were standing in the lobby talking with the organisers. After a short while, Sophia Jansson appeared. She had exchanged her skirt and blouse for outdoor clothes and hiking boots. Roleff Kråkström, the managing director of Moomin Characters Ltd, had put on a similar outfit. In a spirit that Tove Jansson surely would have understood, they were hurrying off to have a look at that active volcano, about an hour’s drive plus an hour’s hike away from Reykjavík.

By Peter Marten, October 2021