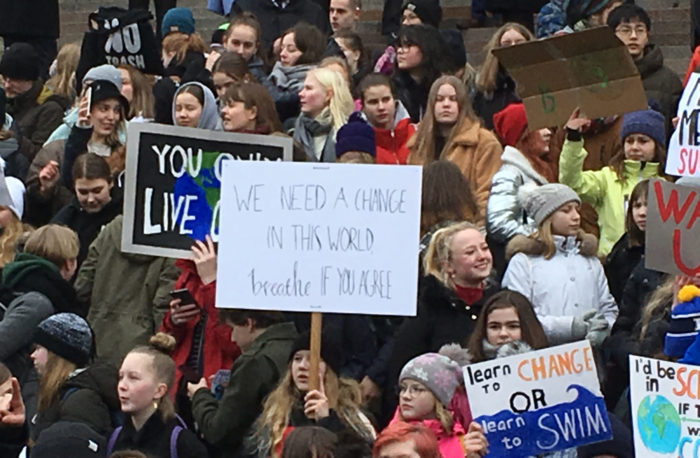

Schoolchildren across Finland went on strike several times in early 2019. Inspired by the Swedish teenage activist Greta Thunberg, they met in dozens of cities and towns to demand action on climate change.

“Our seventh-graders wanted to go, and even made posters,” says Lauri Aho, a geography teacher at Sakarinmäki School, east of Helsinki. “It’s good that they want to be there. They know a lot already, but I’m not sure they understand all the issues yet.”

What can be done

Workers installed solar panels at Sakarimäki School, east of Helsinki, several years ago.Photo: Helen Ltd

A portion of Aho’s job is to make sure the students understand the effects of climate change, how and why it is happening, and what can be done about it. Part of this education is traditional schoolwork using dedicated textbooks, but Finnish kids also get more hands-on training.

“Everyone recycles here,” Aho says, pointing to bins in his classroom. “Our ninth-graders took a field trip to a power station to understand how energy is created. We also had a conference, with different teams representing different nations. They researched the environmental policies of their countries and then debated to get an international treaty like the Paris Agreement.”

Climate change in every subject

“We need a change in this world – breathe if you agree,” reads one sign at a climate action demonstration in Helsinki. Another says, “Learn to change or learn to swim.”Photo: Peter Marten

Teaching about climate change is already important in the Finnish education system, and a new climate studies programme is being developed with the idea that climate change should be part of every subject. Some NGOs have developed climate change and circular economy material that can be used as teachers see fit.

This happens in every Finnish school, but the students at Sakarinmäki School have an advantage: their building has its own supply of renewable energy, which they can study.

“About 80 percent of our energy consumption is from renewables,” says vice-principal Antti Kervinen. “We have solar panels and geothermal heating. We also use bio-oil, but this is only necessary in the winters. Yesterday it was sunny, and 100 percent of our power came from solar energy.”

Seeing energy IRL

Renewable energy is a reality for students at Sakarimäki School – they can see the equipment right next to the school grounds.Photo: Helen Ltd

The students and staff can see their energy production in real time on screens in the hallways. It is shown in typical kilowatt fashion, but also as the equivalent number of warm showers so it is more understandable. This information is incorporated into the school’s curriculum.

“Students learn how to calculate percentages using our school’s energy statistics, such as what percent of our power came from different sources,” says math teacher Heikki Hölttä. “It is also used in physics and chemistry.”

Personal responsibility

Don’t tell them to grow up and out of it: “We’ve got the power – the planet needs action,” the banner says.Photo: Peter Marten

The students are interested in climate change and what they can do about it. A recent survey found that Finnish children and teens increasingly name climate change as a major worry.

“I would have gone to the protests if I had known about it, but I was here taking a maths test,” says Olivia, a ninth-grader. “Greta Thunberg is brave, and it is important to share this information.”

Olivia praises the environmental education she has received at Sakarinmäki and says that school is her main source of information on climate change.

“I’ve probably learned more online,” counters Laura, also a ninth-grader. “I watch a lot of documentaries about the environment.”

The teachers encourage such independent learning, and in fact some projects require it. Aho explains that they also take the time to teach about different sources and how to determine their reliability, because fake news abounds online.

“Some students are very active about climate change, but others are more passive,” says ninth-grader Iisa. “I do what I can, like recycle, always turn off lights when I don’t need them, and eat more vegetarian food at school and at home, but I’m only one person. We look at big countries and wonder why they aren’t doing more.”

By David J. Cord, August 2019