Åland is a group of islands located off the southwestern tip of Finland. Its special autonomy agreement is of interest not only to the local population, but also to many other nations. The archipelago has attracted and continues to attract international attention as an example of how to successfully secure the position of a minority.

The words “war” and “armed conflict” bring to mind classic warfare between countries, but in today’s world such clashes are becoming more of an exception than a rule. Accordingly, many of the armed conflicts currently under way around the globe are internal struggles in countries with some sort of minority issue. Such issues cannot be resolved by creating new, small, independent states ad infinitum. Looking for alternatives to nation building, countries turn their eyes towards Åland, whose autonomy is perceived as a compromise between independence and total integration.

A large number of politicians, reporters and researchers have studied Åland’s autonomy as a potential solution to conflicts. The list of regions and minorities that have led people to take an interest in Åland is long: Israel-Palestine; Nagorno-Karabakh in the South Caucasus region; Northern Ireland; Georgia; Kosovo; Sri Lanka; Aceh in Indonesia; Kashmir between India and Pakistan; Zanzibar; and East Timor. Some have examined Åland’s model in an attempt to avert a crisis, while others are trying to find a solution to a conflict that has already broken out.

Making the constitution work

The sun shines behind an Åland flag billowing at the back of a boat, with islands visible in the background.Photo: Vesa Moilanen/Lehtikuva

How, then, can Åland really serve as an example? Writing a functional constitution is hard, but it is not impossible. There are many experts on international and constitutional law who are capable of framing regulations that protect the rights of minorities, but the real problem is often to make them work in practice.

There is no doubt that Åland has a functioning system of autonomy based not only on a good constitution but also on workable reality. During numerous visits by representatives of various minorities, it has been significant to recall how a minority that initially refused to accept any form of self-rule subsequently built up a well-functioning society with the help of such autonomy. When Finland gained independence from Russia in 1917, Ålanders expressed interest in the islands being ceded back to Sweden. This became the source of some regional tension. In 1921 the Council of the League of Nations put into place guarantees for Åland’s autonomy, and a convention on Åland’s demilitarisation and neutralisation was created.

Åland is a society that enjoys amiable relations with both its motherlands, old and new. What’s more, Åland is a prime example of how autonomy can be extended over time. Every problem does not have to be solved at once; self-government can be expanded at an appropriate moment.

There is full awareness in Åland that no single solution can ever be universally applied to other problems, which is why Ålanders would prefer to speak of their home as an example rather than a model. They have no ambitions of imposing their solution on anybody, nor do they have the power to do so. In fact, the absence of any such power may be a blessing, just like the fact that nobody can suspect Åland of pursuing any self-interest in this matter.

Favourable preconditions help

Boathouses squint against the sun by a bay in Geta, an area of northern Åland.Photo: Udo Haafke/Visit Finland

The preconditions for autonomy in Åland have been and remain favourable. Åland has geographically well-defined boundaries and linguistic homogeneity. Finland is a democratic country based on the rule of law, and controversy over Åland’s affiliation has never included any violence. Such circumstances do not exist in many of today’s conflict areas.

That said, it was never self-evident that Åland would become a success story. After all, the odds are not the best when autonomy is imposed on people against their will, as was the case with Åland. However, Åland’s example shows that a solution with which all the parties were initially dissatisfied can be successful in the long term.

Features of autonomy

Åland is known for its autonomy, but also for the proximity of unspoiled nature in the archipelago.Photo: Tiina Tahvanainen/Visit Åland

Numerous studies on Åland’s political status have shown that the issues attracting interest are wide-ranging indeed. Here are some examples:

1. Autonomy secured by the Finnish Constitution: The Act on the Autonomy of Åland provides for a division of political power between Åland and the rest of Finland. Laws affecting Åland’s status are passed following the procedure prescribed for the enactment of constitutional legislation subject to adoption by the Parliament of Åland (Lagtinget), meaning that the island’s autonomy enjoys very strong legal protection. In practice, this means that Åland can veto any changes to the division of power between Åland and the central government of Finland.

2. Origin of self-government in Åland: The fact that the Åland issue was settled by an international resolution arouses a lot of interest. The decision of the League of Nations was a compromise that took into consideration not only the two countries involved but also the interests of the local population and, above all, the need to protect their language.

3. International guarantees: As a result of the involvement of the League of Nations in the establishment of self-rule, Åland secured international guarantees for its language and local customs. Consequently, the preservation of the Swedish language is both a national and international matter.

4. Language regulations: Åland is the only region in Finland with only one official language (Swedish), whereas the rest of the country is bilingual (Finnish and Swedish). The regulations concerning the language used in administration and education attract a lot of interest.

5. Division of power: The fact that legislative powers are divided between the central government and Åland, and not delegated, is of interest. Many people have studied the question of what legislative powers can be assigned to self-governing bodies and what areas are of such nature that they apply to the country as a whole.

6. Regional citizenship: Regional citizenship, which is a precondition for land ownership and transaction of business, is reserved exclusively for persons permanently residing in Åland. Additionally, regional citizenship is a prerequisite for eligibility to vote in local parliamentary elections.

7. Law and order: The fact that most members of the police force come from Åland has created a degree of interest in places where it is important that the police enjoy the confidence of the local population.

8. The Åland Delegation: The role of the Åland Delegation as an intermediary between the central government and Åland continues to attract interest.

9. Symbols: The flag of Åland is often of great interest to people, just like Åland’s passport, which has the words “Suomi,” “Finland” (the Finnish and Swedish words for “Finland”) and “Åland” printed on the cover, all in the same font size.

10. Influence over international agreements: Even though foreign policy is in the domain of the central government, Åland is not without influence in this area. Under the Act on the Autonomy of Åland, the consent of the Parliament of Åland is required for international agreements affecting the inherent powers of the province; for instance, this provision meant that the Parliament had to take a position on joining the EU along with Finland in 1995.

11. Participation in Nordic cooperation: Nordic cooperation is a noteworthy form of cross-border cooperation. It entitles the Nordic self-governing regions to participate more or less on the same terms as sovereign states.

12. Pragmatism: The people of Åland have always been down-to-earth with little interest in theoretical speculation. For one thing, they have never bothered to discuss whether they should be perceived as a minority, a matter that has generated lively debate and disagreement elsewhere. Instead, the people of Åland have focused on tangible regulations that secure their interests.

Åland as an international example

Calm water reflects a shoreline village in Kökar, southeastern Åland.Photo: Udo Haafke/Visit Finland

Åland has had and will continue to have the resources to respond to the interest that its political status generates worldwide. This helpful openness seems certain to remain part of the character of the province.

Ålanders have realised that it is of great importance for the credibility of the Åland example that representatives of both the majority and minority of the local population have declared that they are pleased with the solution. The central government is also interested in providing information about the Åland solution in situations where it may be of relevance. To this end, the Åland Government and the State of Finland have jointly appointed a contact group under the auspices of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

Even more about Åland

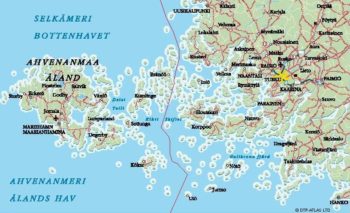

Åland’s location

Åland has a special status in Finland as a demilitarized, neutral and autonomous region. The basis for this rests in the Treaty of Paris that ended the Crimean War in 1856. Their demilitarized, neutral status was confirmed and extended in subsequent treaties, in particular the multilateral Åland Convention, concluded in 1921 on the initiative of the League of Nations.

The autonomous status of Åland is also based on a decision of the Council of the League of Nations in 1921 that resolved a dispute between Finland and Sweden over the islands and is intended to guarantee the preservation of the local language, which is Swedish, and the local culture. Åland has its own representative on the Nordic Council, as have the other Nordic self-governing areas, the Faroe Islands and Greenland.

Åland consists of more than 6,500 islands and skerries, of which 6,400 are larger than 3,000 square metres (32,000 square feet, less than half of a standard soccer field). The current population of 29,000 inhabits only 65 islands, and over 40 percent live in the only actual town, the capital, Mariehamn.

…and a closer view

Nature is perhaps Åland’s greatest attraction. The climate is milder than elsewhere in Finland, the bird population is exceptionally varied and the flora is very distinctive.

The special character of the islands has inspired painters, writers and musicians over the centuries, and today they attract many people interested in sailing, traditional boat-building, fishing, cycling, summer cultural events and historical ruins.

Source: Portraying Finland: Facts and Insights (Otava)

By Susanne Eriksson, senior legal adviser, Åland Parliament; updated June 2017