As a 19-year-old, I visited my Finnish wife (then girlfriend) and her family for the first time in Helsinki. And during that trip ten years ago, my mother-in-law asked me, “What do you like most about Finland?”

I told her I loved its simplicity. But instead of nodding approvingly, my mother-in-law’s eyebrows rose. She looked terribly offended; I assured her that I wasn’t criticising the people.

This Nordic country, I explained, impressed me with its abundance of simple treasures. With saunas; summer cottages; “baby boxes” full of supplies for new parents; and Everyman’s Right, which gives everyone permission to roam the forests and countryside; Finland is a nation where people know how to live well by living simply.

Before moving from Boston to Finland in 2013, I had heard the glowing reports about Finnish schools and I predicted – since Finland was internationally recognised as an education superpower – that I’d discover expensive, flashy ingredients to explain the success of its students on international standardised tests like the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

But when I began a two-year stint as a primary-school teacher in Helsinki, what I found surprised me. I developed a six-letter acronym to describe the key features of Finnish education. It’s SIMPLE: Sensible, Independent, Modest, Playful, Low-stress and Equitable.

Sensible

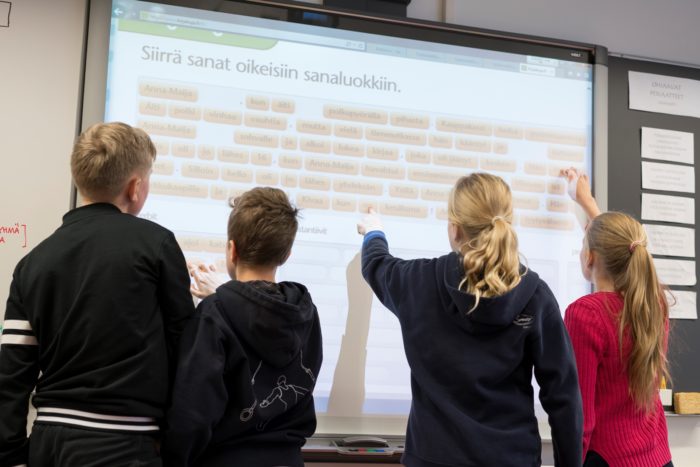

This class activity involves moving words across the screen into different categories according to parts of speech.Photo: Riku Isohella/Velhot

Finland does many sensible things that promote student wellbeing. For instance:

- Students typically receive a 15-minute unstructured break for every 45 minutes of instruction throughout the school day, and research suggests that these frequent breaks promote alertness in the classroom.

- Every school day, all students in Finland – regardless of socioeconomic background – are provided with free, nutritious meals.

- 90 percent of Finnish comprehensive schools are implementing an effective, research-informed program for countering bullying called KiVa, developed at Finland’s University of Turku.

- 70 percent of Finland’s comprehensive schools have adopted a nationwide initiative to boost the physical activity of children, called Finnish Schools on the Move.

Independent

Students in Finland enjoy a great deal of freedom and independence.Photo: Liisa Takala

When I moved to Helsinki, I was shocked to find young children navigating the city’s streets without chaperones. At my school, I witnessed something similar. Primary-school students often walked the hallways without the guidance of teachers, served themselves hot food in the lunchroom, and exited the school on their own – things I hadn’t observed in my home country.

Inside Finnish classrooms, I noticed that many teachers seemed comfortable providing students with ample freedom, such as assigning open-ended projects. Not only did this practice seem to encourage creativity, but it also nudged students to develop stronger critical thinking skills.

Furthermore, Finland’s well-prepared teachers are world-famous for being trusted as professionals who enjoy significant leeway in their classrooms. (Research suggests that teacher autonomy is linked with happiness at work and retaining educators in the teaching profession.)

Modest

Finland’s well-prepared teachers enjoy significant independence in running their classes.Photo: Riitta Supperi/Keksi/Team Finland

When I moved to Finland, I expected to find the latest pedagogical methods, a surplus of classroom technologies and sparkling school facilities. It’s what “the world’s best school system” would offer its teachers and students, I reasoned.

But when I visited different Finnish schools, I generally didn’t find those ingredients. And I’ve since concluded that novel pedagogies, tech gadgets and shiny facilities are nice, but they’re secondary. What’s most important, Finland suggests, is a well-balanced curriculum taught by proficient educators in a learning environment that promotes student wellbeing.

Playful

A learning environment that promotes student wellbeing is one of the most important factors in a good education.Photo: Liisa Takala

In Finland, there’s a widespread belief among parents and teachers that young children need lots of time to play on a regular basis. Research supports this philosophy, too: “In the short and long term, play benefits cognitive, social, emotional and physical development,” according to an American research summary entitled The Power of Play.

In fact, most children in Finland don’t begin first grade until they’re seven years old, and before then, they spend most of their school days learning through play.

But even when Finnish children enter first grade, the structure of the school day provides young students with plenty of opportunities to play. Specifically, most first- and second-graders in Finland, on average, only have about three hours of classroom instruction every day, interspersed with short recesses. And it’s common that, once their school day ends in the early afternoon, Finland’s first- and second-graders attend an after-school club where they typically engage in lots of self-directed play.

Low-stress

Quiet, relaxed learning environments help create a low-stress experience.Photo: Liisa Takala

On my visits to different Finnish schools, I started to notice a pattern: the learning environments were generally quiet and relaxed. Since stress has adverse effects on learning and teaching, a low-stress atmosphere at school is vital for everyone – educators and students.

Equitable

All schools in Finland are public, with the exception of a tiny handful of independent schools, which means that high standards for teaching and learning are widespread. In other words, no matter where in Finland children grow up, they have free access to good schools with skilled teachers, a balanced curriculum, healthy lunches and high-quality learning materials.

Finland’s educational arrangement is simply good for kids.

By Tim Walker, December 2016

Tim Walker is an American teacher and writer whose books are Lost in Finland (2016, S&S) and Teach Like Finland: 33 Simple Strategies for Joyful Classrooms (April 2017, W.W. Norton).