Emmi Itäranta’s novel Memory of Water is unusually successful in many ways. With elements of science fiction and mystery, the story takes place in the future but comments sharply on present environmental and political issues.

In a rare feat, the author herself translated the book. Actually, she wrote it simultaneously in English and Finnish, switching between versions. The US version appeared with a first print run of 50,000 – an impressive vote of confidence in a country known to have a narrow market for translated literature. Memory of Water has made the shortlist for prestigious sci-fi prizes named after influential writers on both sides of the Atlantic: the Arthur C. Clarke Award in the UK and the Philip K. Dick Award in the US.

A primitive future

It’s not entirely correct to call “Memory of Water” translated literature; Itäranta wrote it in both English and Finnish.Photo: Heini Lehväslaiho/Teos

The novel presents a world that is simultaneously futuristic and primitive. The author transports us to a very changed version of our earth that is still within the realm of reality, or even probability. Itäranta’s future world lets her comment on our current events, including environmental threats and trampled human rights.

In the book, the Finnish coastline has changed, leaving much of today’s Finland under water. Drinkable water is scarce and heavily rationed by a brutally repressive military dictatorship.

In a moving passage early on, Itäranta’s teenage main character Noria envisions the past – our present. She gazes over a former landfill site – a “plastic grave” – and tries to understand how people in our time thought and felt, just as Itäranta, in creating Noria’s story, tries to picture the conditions and feelings of the future:

“Their past-world bleeds into our present-world,” Noria narrates. “Did the present-world, the world that is, ever bleed into theirs, the world that was? I imagine one of them standing by the river that is now a dry scar in our landscape….Something that has not yet been is bleeding into her thoughts.”

Noria wonders if the people of the past cared at all about the effect of their actions on the world. Did they try to change their behaviour and make a difference, or were they indifferent?

Parallel visions

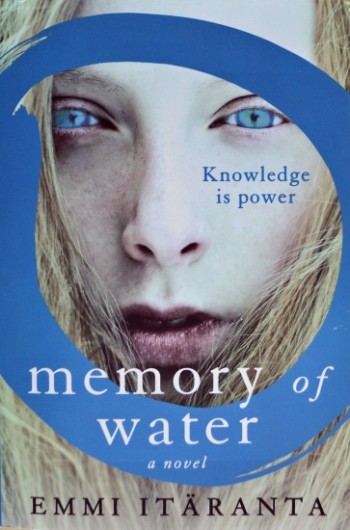

The coverline on one version of “Memory of Water” reads “Knowledge is power;” on another version it says “Some secrets demand betrayal.”Photo: eppujensen/flickr cc by-nc-sa; cover: HarperCollins

It’s not entirely correct to call Memory of Water translated literature. Itäranta, who was born and raised in Tampere, Finland and has lived in England since 2007, wrote the Finnish and English versions in parallel. “I started writing this book while doing a creative writing degree at the University of Kent, so obviously I had to do it in English,” she says.

“Once I had written one or two chapters, I realised that it would be really useful to get some feedback from my Finnish writing group. We meet once a month online. So I wrote those early chapters in Finnish, too. As I was doing that, I began to realise that working in both languages actually helped me polish the writing, because I had to look at it so closely.”

Soon she developed a routine. “Most of the time I ended up writing the first draft of each chapter in Finnish, then I would translate it into English and edit it, making some changes as I translated, then update the Finnish version of the chapter.”

Two things set her method apart from a conventional translation: It goes in both directions between the two languages, and the author herself writes both versions. “Each chapter actually took shape through those two languages,” Itäranta says.

Making your own choices

The cover of the Finnish hardcover edition looks very different. There is also a separate title in Finnish: “Teemestarin kirja” (The Tea Master’s Book).Cover design: Ville Tiihonen/Teos

The teenager Noria is a tea master’s daughter, and will soon take the test to become a tea master herself. The tea ceremony tradition, transplanted to Finnish territory generations before the story begins, forms a powerful symbol in a world where water is limited.

The title Memory of Water invites interpretation: the society in the book has only a collective memory – if that – of plentiful, clean water as Finland knows it today, but the water in the story can also be said to carry and reveal its own memories and reminders.

Water also offers a vehicle for commenting on dictatorial politics and environmental inaction. The novel’s description of military dictatorship seems to pass judgement on the conveyor belt of dictators that we see in the news today. “It was intentional,” says Itäranta. “I thought, What would the political consequences be if drinking water was such a valuable, scarce resource? Dictatorships control resources as a tool of power to control people.”

“I think that as a species we have a built-in capacity for self-destructive behaviour, but also a built-in capacity to improve things, to make a change,” she says.

All this is framed by the events of Noria’s life. “The story is really about coming of age and learning to make your own choices rather than taking for granted what your parents have told you or what society tells you,” the author says.

“Sometimes you have to make a choice that may not help you, but you know it’s the right thing to do.”

By Peter Marten, May 2015