There’s something foreboding about Finnish artist Jaakko Niemelä’s Quay 6.

The scaffolding installation greets Helsinki Biennial visitors as they arrive by ferry from the city centre and disembark on the island of Vallisaari. Seen from the sea, with water dripping down its sides, the wooden structure is impressive and disquieting in equal measure.

Quay 6 is one of the works in the first edition of the Helsinki Biennial art festival, subtitled “The Same Sea.” Niemelä has long been interested in the impact of climate change on the archipelago, and Quay 6 offers a striking visual representation of an all-too-possible future: the structure is six metres tall (19 feet 8 inches), roughly the amount by which global sea levels would rise if Greenland’s northern ice sheet were to melt.

An unnatural colour

If Greenland’s northern ice sheet melts, global sea levels are predicted to rise six metres (19 feet 8 inches), to the level marked by the top of Jaakko Niemelä’s installation Quay 6. Photo: Maija Toivanen/Helsinki Art Museum/Helsinki Biennial 2021

“When I heard that one of the biennial’s themes is the sea we share, I was delighted,” says Niemelä. “I’m the son of a sailor, so the sea is very important to me.” Quay 6 would collapse if just one part of the structure were removed – a nod to the festival’s theme of interdependence – but it is also, quite simply, a warning.

“That’s why I chose to paint the top red,” explains Niemelä. “Red is not a natural colour. It shouldn’t be here.”

After a one-year postponement because of the Covid-19 pandemic, the first Helsinki Biennial commenced in June 2021, lasting until September 26. (ThisisFINLAND has covered it from the start).

Outdoor commissions

A painting “can land anywhere,” says Katharina Grosse. In this case, her colours have found a disused schoolhouse slated for demolition after the biennial is over. Photo: Maija Toivanen/Helsinki Art Museum/Helsinki Biennial 2021

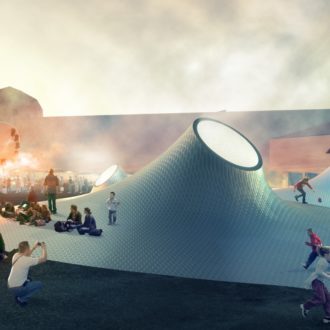

Vallisaari has a history as a military outpost going back to at least the 1700s; it has been open to the public since 2016. The biennial displays pieces by 41 artists from Finland and around the world. The artworks, 75 percent of which are new commissions, reflect on themes of interconnectedness and mutual dependence whilst also engaging with Vallisaari’s past.

Outdoor commissions incorporate the island’s natural environment. These include an immersive sound installation in the shade of ancient linden trees, by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller; Katharina Grosse’s colourful painting that sweeps across an old schoolhouse and its surrounding vegetation; and Tadashi Kawamata’s lighthouse structure, made from waste material found on Vallisaari and visible from Suomenlinna, a nearby island fortress that is one of the Finnish capital’s landmark tourist sites.

The voices of the foremothers

The festival also features a range of artworks inside Vallisaari’s historical buildings and gunpowder storage areas. One is an installation by Sámi artist Outi Pieski – the Sámi are the indigenous people whose homeland is divided into four parts by the borders of Finland, Sweden, Norway and Russia. Her piece Guhte gullá / Here to hear projects video footage onto the walls of a cave-like chamber. In it, Birit and Katja Haarla dance to electronic music and Sámi yoik vocals.

“Young people dance to escape the angst of world destruction, summoning the aid of the forgotten Sámi earth deities Uksáhkká, Juoksáhkká and Sáráhkká,” says the exhibition description. The installation attempts to raise awareness: “Women of different generations listen to the voices of their foremothers through dance and duodji, traditional Sámi handicrafts.”

Camouflage climates

In Carbon as a Political Molecule, Baran Caginli pieces together a map using camouflage patterns from around the world. Photo: Maija Toivanen/Helsinki Art Museum/Helsinki Biennial 2021

Inside Vallisaari’s former military headquarters is Helsinki-based Turkish artist Baran Caginli’s Carbon as a Political Molecule, a world map patched together from camouflage used by armies around the world. “Armies design camouflage patterns to match their local climates,” says Caginli, “so I covered each country in its own military pattern.”

Caginli’s work comments on environmental disasters caused by war, and on the arms industry as an instrument of capitalism. “This is a former military island,” Caginli says. “The top of the island is still closed to the public. In my work, I’m trying to make a point about the extent to which the military plays a role in environmental destruction.” On Vallisaari itself, a series of ammunition-depot explosions in 1937 killed 12 people; this is one reason that land use is still restricted in parts of the island.

Because of the pandemic, many of the biennial’s artworks are also viewable online, including Becoming, a video work by writer Laura Gustafsson and artist Terike Haapoja. Placing three screens side by side, they talk with activists, thinkers, artists, caregivers and children in Finland and the US about “new, healthier ways of interacting with other people and lifeforms.”

New views

Geese fly past Tadashi Kawamata’s temporary landmark, Vallisaari Lighthouse, made from material found on the island. Helsinki is visible in the distance, including the towers of Saint John’s Church, to the left of the lighthouse. Photo: Maija Toivanen/Helsinki Art Museum/Helsinki Biennial 2021

According to curator Pirkko Siitari, postponing the biennial from 2020 to 2021 only strengthened the relevance of its theme. “Now more than ever, we understand that we have a very problematic relationship with nature,” she says. “It’s clearer than ever before that everything is interconnected.”

The majority of the biennial’s art is on display only until the event closes in autumn 2021, although sculptures by Alicja Kwade and Laura Könönen will be relocated to the Helsinki neighbourhoods of Kalasatama and Jätkäsaari, respectively, for permanent display.

After more time than ever spent at home during Covid-19 lockdowns, the biennial offers visitors a welcome opportunity to get out and reflect on what togetherness really means, all while interacting with contemporary art in Helsinki’s stunning archipelago. If you can’t make it to Helsinki for reasons of geography or corona restrictions, the biennial’s artists and artworks may still inspire you online.

By Tabatha Leggett, July 2021