A great deal of international attention has been attracted by the repeated success of Finnish 15-year-old pupils and their level of ability as measured in the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) studies organised by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development).

Thumbs up for education: This Finnish language and literature textbook is named after famous author Aleksis Kivi (1834–1872).Photo: Lehtikuva

Free, equal education for all

One of the Finnish education system’s major strengths is its ability to guarantee the same educational opportunities for everyone, regardless of social or economic background. Instead of competition and comparison, comprehensive school focuses on support and guidance for the students as individuals.

Teachers are highly trained; teaching at all levels of education requires a master’s degree, including extensive studies in educational science and in school subjects. The teaching profession is held in high regard.

Finnish schools encourage pupils to be independent when thinking, studying and doing research.Photo: Ministry of Education and Culture/L.Takala

Young pupils have the same teacher for all or most of the subjects, which supports them emotionally and provides a sense of security. The same teacher also makes sure the class atmosphere remains free of discrimination and harassment. Graded evaluation of learning performance usually starts only once students reach the fifth year. Relations between the students and teachers are friendly and relaxed, and motivation is based on encouragement rather than punishment.

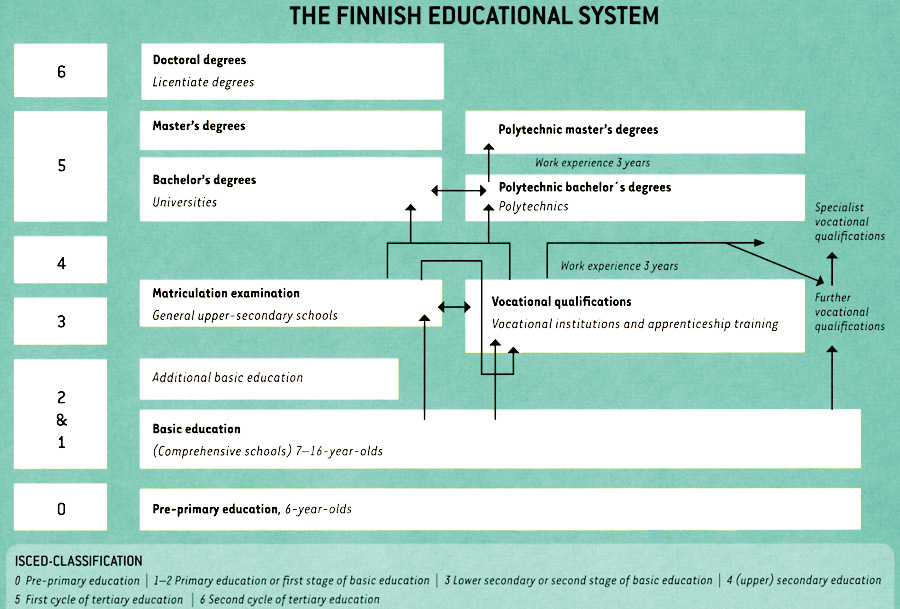

After comprehensive school, all students have the opportunity to focus their attention on general and professional education according to their inclinations. People can continue to study in various forms throughout their lives. Twenty-five percent of all Finns hold a degree from a university or polytechnic; the figure is 36 percent for the 25–34 age group.

Education is free from preschool through university. Using tax revenues to finance education ensures high quality and equal opportunities for all.

PISA: Finnish youth at the forefront

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Finland ranks at or near the top in all the PISA studies, organised every three years since the year 2000 by OECD. PISA measures the competence of 15-year-old pupils in mathematics, science and reading literacy. It is particularly noteworthy that among Finnish schoolchildren the difference between top-scorers and low-scorers is small, and that ability levels are strong in all types of schools.

“Education is security for a small nation”*

* J.V. Snellman (1806–1881), a philosopher, scholar, journalist and politician

who played a unique, important role in forming the Finnish national identity

Finnish children start school the autumn of the calendar year that they turn seven. This gives them a longer time to play, use their imaginations and develop secure attachment before attending school.Photo: Amanda Soila

In the modern world, a well-educated, skilful population forms the key to a country’s success.The rise of Finnish society to the ranks of the world’s richest countries in the second half of the 1900s stemmed largely from the population’s demand for public education and the country’s investment in it.

As early as the 1800s, major decisions sowed the seeds for the continuing success of the education system. Finland decided on education for the entire nation. In this way, the country avoided social inequality between an educated elite and an uneducated lower class. The population’s desire to learn has also contributed to a general faith in education. People are expected to stay informed about a wide range of issues and societal concerns.

Solving global problems through education

Finding solutions to the challenges facing society – climate change, global economic fluctuations, an ageing population, risks connected with modern technology, pandemics and mass migration – calls for lifestyle changes and new kinds of activism. In Finland and everywhere else in the world, a growing flood of information and the movement of people are now creating new challenges for traditional education. No matter how strong an education system is, it needs constant development and renewal to maintain its success. The better educated a nation is, the better it will be equipped to face the complex challenges of today’s world.

Education forms the cornerstone of democracy and modern society

“The high level of the Finnish school system is backed by a clear national ethos that says the people are the nation’s most important resource and they have a right to a quality education,” says the director of general education Jorma Kauppinen of the Finnish National Board of Education.

School days in Finland are shorter than in most OECD countries, but the time spent at school is used effectively.Photo: Ministry of Education and Culture/Liisa Takala

Between 11 and 12 percent of the Finnish state and municipal budget is spent on education. This pays for free preschool, basic education, upper-secondary school, vocational training, higher education and continuing and post-graduate studies, and partially funds liberal adult education. This, in turn, forms the backbone of lifelong learning, available to everyone who lives in Finland.

“The establishment of the primary school system was linked to the awakening of a strong national consciousness,” Kauppinen says. “The nation needed literate, educated citizens and a literary culture.”

The majority of Finnish municipalities had primary schools by the early 1900s. The Compulsory School Attendance Act came into force in 1921, requiring all children to complete at least six years of primary school.

A major turning point came about in the 1970s, when primary and secondary schools were replaced by mainly municipal nine-year comprehensive schools compulsory school attendance was lengthened to nine years. The comprehensive school reform aimed to guarantee equal and free basic education for all children, regardless of the family’s place of residence and socio-economic status.

Play and nurture prepare kids for school

School starts comparatively late in Finland, at the age of seven. According to Finnish educational practice, children need time and space to grow and develop. Learning utilises a sensitive period in children’s lives and encourages their thinking and creativity. During the early school years, families receive verbal feedback on the child’s schoolwork.

In early childhood years, children enjoy the care and nurture of their parents. Kids also participate in group activities at daycare: play, sports and outdoor activities. Parents of young children are ensured long periods of maternity and parental leave. Families can also choose between municipal and private daycare centres, or opt for small group daycare in a child carer’s home.

Six-year-old children have access to free preschool education, either at a school or at their daycare. Nearly all six-year-olds participate in preschool.

If necessary, a child may start school a year earlier or later after an evaluation assesses their school readiness.

Local schools and trust create high-quality schooling

Finland contains approximately 3,000 comprehensive schools with a total of 550,000 students. In practice, the municipalities are responsible for organising the teaching. In one of its most significant findings, the PISA study concluded that out of all the participants, Finland has the smallest differences between schools.

“This result stems from the local-schools principle, highly educated teachers and a culture of trust,” summarises Mr. Kauppinen.

The local-schools principle means that almost all children and young adults attend the school closest to their homes, pre-empting divisions according to family social status. Since schools maintain a reliably high standard, parents are generally satisfied with their local schools, and elite private schools have not emerged alongside local comprehensive schools. Subject to licensing, private schools exist to some extent, but they also receive state funding and follow the national curriculum, and are obliged to include pupils from the local district.

Municipalities fund school transport for children who live too far away to walk or to use public transport.

Teachers select their teaching methods

Teacher training includes both pedagogical skills and in-depth knowledge of curricular subjects. Although the curriculum and the learning objectives are decided at the national level, teachers can choose their methods freely in the classroom.

Students receive support and guidance in small groups as necessary.Photo: Amanda Soila

“Power is delegated to municipalities, schools and ultimately individual teachers, with all levels of educational administration interacting and sharing notes,” explains Kauppinen. “This culture of trust produces teachers who are independent experts.” On one hand, they are familiar with their own students’ needs and opportunities, and on the other hand, they respect national curricular objectives.

High-quality teaching materials hold great importance. Large investments support the production of school books and other learning materials in Finnish as well as Swedish, Finland’s other official language. Materials are increasingly available in electronic form and online.

Kauppinen believes that the future challenge for schools will be in developing cooperation between home and school, and in advancing dialogue between schools and the surrounding society.

Teacher education ensures quality teaching

All comprehensive school teachers with a permanent full-time post hold a university degree.

In primary school (grades 1–6), teachers usually teach all subjects. They hold a master’s degree in education with an emphasis on pedagogical skills. In both lower secondary school and upper-secondary school, subject-specific teaching is provided by teachers who have completed a master’s degree in their respective fields and have completed studies in educational science.

Daycare and preschool teachers are also university graduates.

Teacher education is a very popular field, and enjoys high esteem in spite of the relatively modest level of pay. There are five times as many applicants for teacher education as there are places.

Education for all stages of life

Young pupils spend recess playing outside, rain or shine.Photo: Amanda Soila

Finns are offered free education throughout their lives, from nursery school to the highest academic degrees.

Young Finns complete their compulsory education in comprehensive secondary school. Their compulsory education ends when they have either completed the entire 9-year basic education curriculum or, at the latest, by the age of 16 years old.

After comprehensive school, half of all pupils go on to upper-secondary school – approximately 60 percent of the girls and approximately 42 percent of the boys. Upper-secondary school studies last two to four years, culminating in the matriculation examination.

The other half of the same age group goes into vocational studies. Approximately 5 percent of those who complete comprehensive school do not continue studying. The goal, however, is that everyone completes at least upper-secondary education, i.e. the matriculation examination or a basic vocational qualification.

After upper-secondary school, students can decide whether they will go on to higher education at a university or polytechnic. The selection process takes into account the matriculation examination results and upper-secondary grades, and most departments also require an entrance examination. Students may also apply to university or polytechnic institutes if they have completed a three-year professional degree or the equivalent, so they may seek higher education even after vocational school. The system aims to prevent dead ends in all areas of education, including vocational education, so that it is always possible to progress to higher studies.

Those who have graduated and worked in a profession can access further vocational training or study an entirely new profession. In many fields, studies can be completed as on-the-job training under an apprenticeship scheme. People who have practised a profession may also prove their skills by taking a competence examination.

Central and local government broadly support basic education directed at creative hobbies and arts for children and youth, as well as liberal adult education that offers all-round education and classes based on hobbies and social interests.

Positive interaction supports human growth and development

School days start at 8:30 am and end no later than 3:30 pm.

Photo: Ministry of Education and Culture/Liisa Takala

An ordinary school day at Meilahti Comprehensive School in western Helsinki is about to begin. Pupils hurry to their lockers and classrooms. There are merry greetings as pupils pass by each other; some of the greetings are also directed towards the principal, Riitta Erkinjuntti, whose door onto the main hall is open.

“Teachers and pupils are always welcome to come and see me when the door is open, and it is nearly always open,” says Erkinjuntti.

The school atmosphere is relaxed and tolerant, as it is in most Finnish schools. The pupils relate to each other respectfully but casually. Students call teachers by their first names and classes are taught in a very conversational manner.

Principal Riitta Erkinjuntti of the Meilahti Comprehensive SchoolPhoto: Amanda Soila

“Teaching is based on support, participation and interaction. The pupils work hard, but are not forced to do so by demands, intimidation or pressure,” says Erkinjuntti.

Her school has about 350 pupils in secondary school, classes 7 to 9. The pupils are from 13 to 16 years old. In addition to regular secondary school classes, the school also has art and music programmes. A bilingual Chinese-Finnish study group also exists, as well as a language immersion class where Finnish-speaking pupils study part of the day in Swedish, effortlessly learning the country’s second official language. There are special preparatory classes for immigrants and training classes for pupils with mild mental disabilities. Children in the special classes may come from outside the local school area.

“For pupils, it is good that they encounter all kinds of learners in their school environment, representing different cultures and different sorts of young people,” says Erkinjuntti. Many other Finnish schools use the same approach.

School days start at 8:30 am and end no later than 3:30 pm. The secondary school curriculum includes a lot of mathematics, Finnish, at least two foreign languages, humanities, natural sciences and art, as well as two hours of physical education every week.

Special support for pupils with learning difficulties

According to international assessments, one of the special strengths of Finnish schools is the way the schools support students who are struggling with learning difficulties or need other support. You cannot get through Finnish school without developing basic skills in reading, maths and other areas. Every child and young person has the right to a quality education, regardless of his or her personal conditions or limitations.

Pupils are entitled to special assistance as soon as the need arises. Common forms of support include remedial teaching in small groups, individual counselling and teaching pupils in accordance with individual conditions, even when they are studying in the same class as others. Most schools have special teachers and nearly all have visiting teaching assistants to help with needy pupils. If a child is found to have a wide-ranging, permanent learning difficulty, a personal learning plan is formulated for the pupil. Pupils with mild to moderate learning difficulties study in the same schools and classrooms as everyone else, but the schools receive additional resources in these cases.

Pupils with mental disabilities and children with severe sensory or physical disabilities or special health or mental health problems study in special classes or schools, and for some of them compulsory education lasts 11 years.

Children of immigrants receive many kinds of support at school. Those who do not speak Finnish or Swedish well are offered preparatory education in small groups where they get to learn the Finnish language with an adapted syllabus. In major cities, children from immigrant backgrounds have access to language lessons in their own mother tongue.

Artistic subjects help develop personality

The enthusiasm of the students and teachers at Meilahti Comprehensive is enhanced by cooperation with various organisations, including art institutes, sports clubs and the local church. A variety of projects help the school keep up with developments in computer technology and other areas. Meilahti produces good learning results, and has been selected once as a PISA school.

“Our school system makes it possible for schools to avoid constantly competing against each other,” says Erkinjuntti. “We focus on supporting pupils based on their own unique situation.”

Arts and practical subjects are particularly important in this respect.

Student wellbeing and interaction between students are two areas that receive special attention.Photo: Ministry of Education and Culture/Liisa Takala

“Subjects where you can express yourself support a balanced, growing personality. Gifted students have the opportunity to go deeper into these subjects in special classes. This helps improve motivation and provides an additional challenge.”

Principal Erkinjuntti believes that the success of Finnish schools is largely due to the values and human image of the school community. A young person can acquire knowledge and skills more readily when she or he feels accepted, respected and trusted. Bullying and other issues harmful to wellbeing are addressed without delay.

In Erkinjuntti’s experience, some of the most significant challenges connected with childhood education are parents’ lack of time and young adults’ need for more attention from the grown-ups in their lives. In modern society children often have to grow up too fast. They have to become independent and resilient early on.

Another challenge is the flood of information. “We live in a world of unlimited information, and this also affects schools,” says Erkinjuntti. “How will the schools of the future determine what to focus on? Where do you draw the line?”

Ensuring student wellbeing

Each school has a student welfare unit and school health services. Student welfare has to do with the school’s responsibility for social, mental and physical wellbeing. The school may act if pupils shirk school, are chronically late, become marginalised from the class community, use drugs or alcohol, or suffer from an unstable family situation. In these cases, the adults in the school have a right and a duty to work towards a solution together with the parents, and, if necessary, to turn to municipal healthcare, child welfare or social services for advice.

Schoolchildren receive regular health and dental check-ups and, if necessary, are sent for further examination to the municipal health services. School health services are free of charge.

“The best thing is the active and supportive atmosphere”

Oona Niemelä (centre) checking graphic prints with her classmates.Photo: Amanda Soila

Ninth-grader Oona Niemelä’s day at school

Fifteen-year-old Oona Niemelä wakes up before seven and eats breakfast with her family. Then she takes a half-hour bus ride to school. She studies in the ninth grade at Meilahti Comprehensive School with an emphasis on visual arts.

Meilahti is not the closest school to Oona’s home, but she applied there specifically for the visual arts programme.

“For the entry test, I had to do a pencil drawing and a watercolour painting,” Oona says. “I was nervous, but luckily I passed.” In her opinion, the best thing about Meilahti Comprehensive is a positive environment that encourages students to stay active. You do not have to be worried about being bullied at school.

Oona’s favourite subjects are the visual arts and languages. She likes physics and religion less.

“Homework takes about an hour and half a day, but before tests I study longer. I don’t usually need my parents’ help to do my homework.”

Oona’s school days last five to seven hours. Each morning and afternoon includes a 15-minute recess, and halfway through the day there is a half-hour lunch break. During the breaks, she mingles with her friends; in good weather they are outside in the schoolyard.

After school, Oona keeps busy with her hobbies. She takes piano lessons at a music school and goes horseback riding once a week. Oona gets to her hobbies independently on public transport, just as most young people do in Helsinki.

Evenings include homework and piano practice. Oona also spends time chatting with friends online, talking on the phone and watching television. With so many activities during the week, she hangs out with her friends mostly on weekends.

The lights go out in Oona’s room at about 10:00 pm.

After comprehensive school, Oona is planning to go to upper-secondary school. She would like to attend Sibelius High School, where they offer a special music programme.

“I’m not really planning a career in the arts, but I think it would be nice to get more into music and art, just for my own sake,” Oona says.

More info

The Finnish educational system

Source: Ministry of Education and Culture

Standardised educational objectives

The government decides on the general objectives and the division of hours between comprehensive and upper-secondary school subjects. This is based on the national curriculum, which is decided on by the Finnish National Board of Education under the Ministry of Education and Culture. Education providers, most of which are the municipalities, then develop their own curricula and school-specific plans based on this foundation. In this way, all pupils across the country receive the same subjects at the same level and quality. At the same time, the system also allows for local emphasis and enhancement.

Students’ learning outcomes in comprehensive school are monitored by national assessments, involving a random sampling of about 5 percent. Additionally, those responsible for organising the teaching are required to perform evaluations on a regular basis.

Upper-secondary school studies culminate in the national matriculation examination, assessed by the National Matriculation Examinations Board.

Photo: Amanda Soila

Curriculum includes free lunch

by Minna Kantén

Every child in a Finnish daycare centre, elementary or secondary school or vocational college is provided with a hot, healthy lunch including salad, milk and bread.

The free lunch served at school forms a component of the official curriculum. The idea is that a meal break at school refreshes the children and helps them through the remainder of the day. At the same time it is a lesson in health, nutrition and customs.

In some pioneering schools, the students are offered climate-friendly meals such as vegetarian and organic lunches.

Schoolchildren’s favourite lunch menus

- Lasagne

- Minced-meat-and-macaroni casserole

- Spinach pancakes

- Meatballs

- Minced-meat sauce

- Fish fingers

- Minced meat and mashed potato casserole

- Barley porridge

Photo: A. Soila

By Salla Korpela

Published May 2012, updated July 2014