So many international rankings and reports exist. What sets the Good Country Index apart from the Global Competitiveness Index, the Prosperity Index, the World Happiness Report, the Environmental Performance Index and all the others?

The Good Country Index takes stock of 35 measurements that show countries’ contributions in seven different categories: science and technology; culture; peace and security; world order; planet and climate; prosperity and equality; and health and wellbeing.

In addition, and perhaps most importantly, the Good Country Index is all about what nations do for the rest of the world, not about what happens within their own borders.

A toe in the water

Simon Anholt founded the Anholt Nation Brands Index in 2005 and the Good Country Index in 2014.Photo: Sara Gibbings/Troy TV

“Pretty much every single one of [the other indexes] looks at countries’ internal performance in one way or another,” says Anholt. “Consequently, [they] treat the world as if it were made of entirely separate independent islands of humanity that have nothing to do with each other.”

Since the 1990s, London-based Anholt has advised the leaders of more than 50 countries in what became known as nation branding. In 2005 he founded the Anholt Nation Brands Index. Gradually perceiving a need for a new kind of study, he inaugurated the Good Country Index in 2014. (Finland was second that year.)

“Because we live in a massively interconnected, interdependent age, an age of advanced globalisation, it also made a lot of sense to look at how countries affect each other and affect the whole system,” he says.

While the Good Country Index gathers an immense amount of data, he characterises it as “a toe in the water;” it has limitations. “Reducing a country’s impact on the world to 35 data sets is obviously just a hint.”

Conversation and cooperation beat competition

Teenage students gathered in January 2019 outside Parliament in Helsinki to demand action on climate change. Simon Anholt believes that people can use the Good Country Index to help hold politicians to account, for example by focusing on key topics during election season.Photo: Mesut Turan/Lehtikuva

The index also offers opportunities: “It is supposed to be the start of a new kind of conversation. The reason for it is to get people to start asking new questions about countries.”

This holds true no matter where your country ranks. In fact, the word “ranking” is misleading. The Good Country Index aims to encourage conversation, collaboration and cooperation, rather than competition to see who “wins” the rankings race.

“I’m not judging,” says Anholt. For this reason, the various categories of data aren’t weighted in the overall results. “I publish it in the form of a ranking because that’s the easiest way to crunch all of that data and present people with an overall picture.” A comparative listing gets people discussing the results.

After the release of the first edition of the index, Australian political activists told him they used the data matrix of the Good Country Index to focus questions for election candidates about how they would address certain categories in which the country was underperforming. “It’s a tool,” says Anholt. “If people do choose to use it to hold their governments to account, then that’s great. That means it’s working.” Finland is holding parliamentary elections in April 2019, and European Parliament elections happen in May 2019.

Sharing inspiration and experience

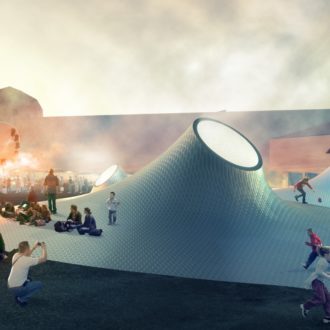

Finland, Sweden, Norway and Denmark possess a long history of regional cooperation and often find themselves at the top of the Good Country Index.Photo: ESA/eyevine/Lehtikuva

While the Good Country Index aims to encourage discussion and cooperation, it’s not against the idea of competition. If countries vie to be the “goodest,” that’s healthy.

“Competition is fine,” says Anholt. “It’s a very effective driver, but it only becomes a problem when it’s the only altar at which we worship, and that’s the case for most countries most of the time.” He believes that “the culture of governance worldwide” can shift from fundamentally competitive to fundamentally collaborative.

Work together a little more, compete against each other a little less; this is his straightforward suggestion. The Nordic countries, who possess a long history of regional cooperation, often find themselves at the top of the index (the newest results put Sweden, Denmark and Norway in third, fifth and seventh place).

What’s good for your neighbours and the rest of the world is frequently good for you, too. “You often end up doing better work domestically because you’re drawing inspiration and experience from other countries,” Anholt says. “You’re sharing good ideas.”

Finland’s strengths

A walk in the park: One of the subcategories in which Finland does well is compliance with environmental agreements.Photo: Pasi Markkanen

Out of the seven categories in the Good Country Index, Finland places highest in prosperity and equality, in which it is second. The 35 subcategories include birth rate; ecological footprint; renewable energy; giving to charity; accumulated Noble Prizes; creative goods exports; humanitarian aid donations; and number of UN volunteers sent abroad.

Finland’s strong suits are freedom of movement; press freedom; number of patents; number of international publications; foreign direct investment outflow; food aid funding; compliance with environmental agreements; and cybersecurity. One area for improvement is international students: Finland is famous for its education system, but figures indicate it should do more to attract foreign students.

“My message to Finland is the same message I would give to any country that comes top of the index,” says Anholt. “This is not a reward. Who am I to reward a country for its behaviour? This is a message about your obligations.”

Doing well in the Good Country Index indicates that a nation is good at collaborating and has “figured out a few things” that some of the others haven’t, says Anholt. It should “continue to demonstrate the benefit – domestic and international – of enhanced cooperation and collaboration.”

It’s about countries “making [themselves] willing and available to work with other countries,” says Anholt. “So it’s an opportunity for Finland to start working with other countries in a new way.”

The most obvious case

Light shines into Helsinki University’s main library: The Good Country Index suggests that Finland should do more to attract foreign students.Photo: Sakari Piippo

“Countries working together” has hardly been a common rallying cry among politicians in recent years. We constantly hear the word “polarisation” in the news.

“If this isn’t the most obvious case for more cooperation and more collaboration, then what is?” asks Anholt. He’s talking about cooperation between people who are concerned about the world as a whole and those who focus more on their own countries. Both have validity, he says. “It’s very important that the Good Country Index doesn’t become another piece of tribalism.”

The measurements in the index point to difficult questions about climate change, human migration, healthcare, poverty and more. How do you stay positive when your work involves delving into these stats?

You create a country. In Anholt’s newest project, he and American Madeline Hung have cofounded the Good Country, most easily described as a virtual country, “to prove that if countries learn to work together, then we will start to make real progress.” Anyone who wants to participate in solving global challenges can sign up online and become a citizen.

In real life, Finland will continue to consider how its actions can contribute to humanity. At the moment, that’s the “goodest” thing to do.

By Peter Marten, January 2019