“Excuse me, where are the Donald Duck paintings?” The staffers in the galleries of Helsinki’s Ateneum Art Museum heard this question thousands of times over a space of several months. Another thing they often heard is, “I’ve never been to a museum before, but I came to see the ducks.”

Ateneum negotiated with the National Gallery of Duckburg – or so the story goes – to gain the privilege of exhibiting more than a dozen pieces that show remarkable similarities to classic Finnish artworks in Ateneum’s own collection. The National Gallery of Duckburg exhibition ended on February 25, 2018, but we couldn’t let its runaway success just fade away; our slideshow (below) contains a selection of paintings for anyone who couldn’t make it to Helsinki to see them.

Duckburg is, of course, the city chronicled in the Donald Duck comic books, which hold a special place in the hearts of the Finns, for reasons we’ll get into shortly.

The curators intentionally designed the exhibition so that the location of the Duckburg paintings wouldn’t be immediately obvious. They didn’t have their own room. Instead, they popped up throughout the museum near the Finnish classics that they resemble, mostly in Ateneum’s long-term show, Stories of Finnish Art.

National Gallery of Duckburg created an additional level within Stories, which already contains many layers of meaning. Stories covers a period from the early 1800s to the late 1900s and is arranged salon-style, each wall a constellation of paintings hung close together. Finnish classics and lesser-known works appear side-by-side with those of foreign artists, inviting viewers to notice how artists influenced each other and how Finland’s art world interacted with movements abroad.

The Donald Duck pieces added another dimension by echoing their Finnish counterparts. [Article continues after slideshow.]

Donald’s Finnish role as Aku

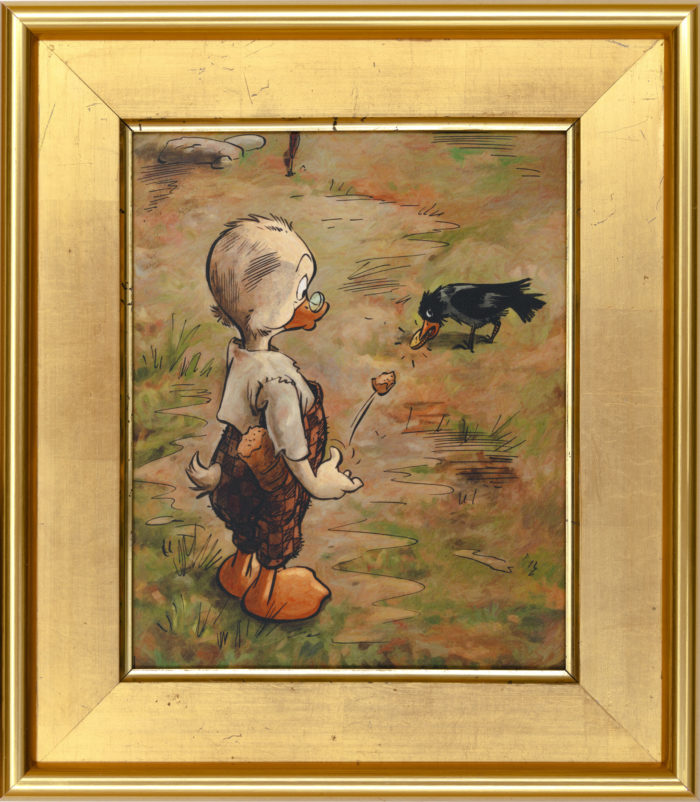

“Duckling with a Crow,” by Audubon Gander-Kallela, shows Scrooge McDuck earning his second-ever coin. He traded a crow a piece of bread for the money. Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/ Finnish National Gallery/National Gallery of Duckburg

“Boy with a Crow,” painted in 1884 by Akseli Gallen-Kallela, one of the major figures in Finland’s art world, may well lead viewers to ask which came first, “Boy with a Crow” or Audubon Gander-Kallela’s “Duckling with a Crow”? Photo: Yehia Eweis/Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery

“Duckburg Town Square” by Albert Eiderfelt bears a marked similarity to another composition, “The Luxembourg Gardens, Paris,” an 1887 oil painting attributed to an artist with a conspicuously analogous name: Albert Edelfelt. Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery/National Gallery of Duckburg

One of the great things about art is that everybody can devise their own interpretation and find an entry point. “That’s a park in Paris,” says a man to his daughter, who is perhaps six years old. “No,” she says, “that’s in Helsinki.” “The Luxembourg Gardens, Paris” (1887) by Albert Edelfelt; Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery

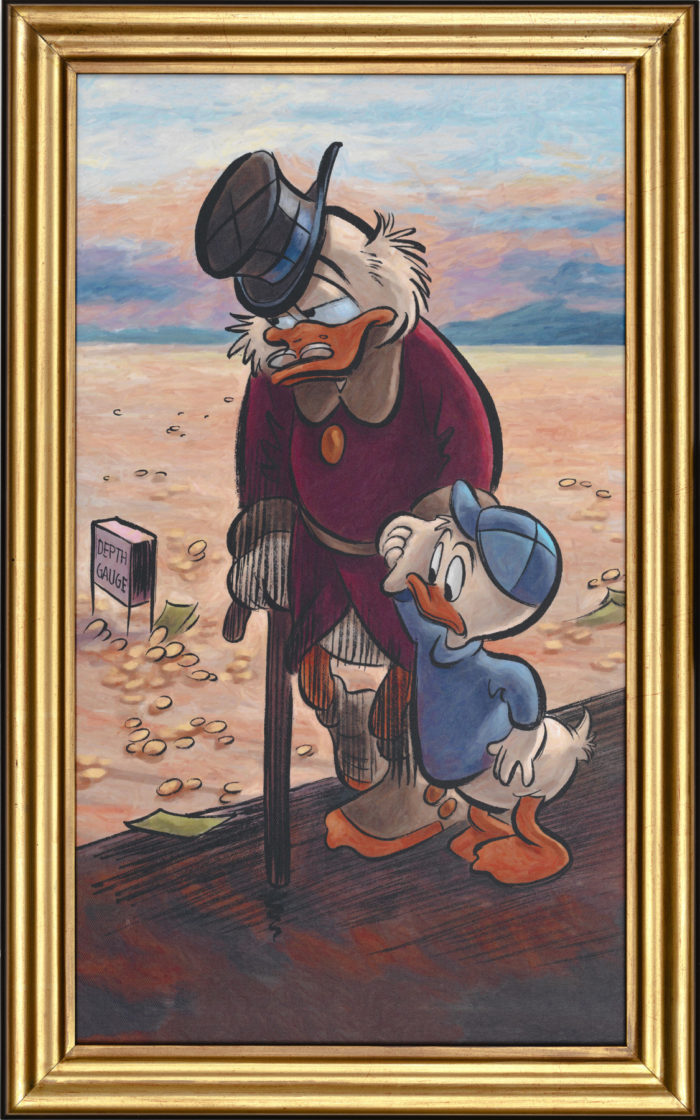

“Towards Evening and Poverty” is “a masterpiece of Hookbill Simberg’s mature period,” according to the curators. The sea of money shows that “owning three cubic acres of hard currency is a formidable burden.” Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery/National Gallery of Duckburg

Hugo Simberg painted his son walking with the artist’s father in “Old Man and Child” in 1913 with “an exceptionally subtle and sympathetic quality,” as the wall placard tells visitors. Photo: Yehia Eweis/Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery

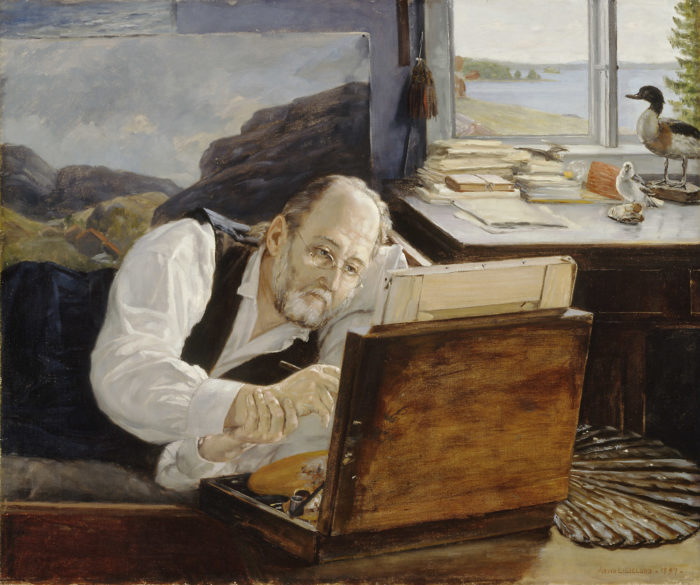

Arvid Liljelund painted “Ferdinand von Wright at Work” in 1897. Von Wright, who suffered from the effects of an illness during the last two decades of his life, painted in a reclining position. He and his brothers were famous for their portrayals of birds and landscapes. Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery

“Gus Goose at Work” by Arvid Le Loon bears certain similarities to Arvid Liljelund’s portrait of Ferdinand von Wright, although Goose doesn’t seem to share von Wright’s work ethic. Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery/National Gallery of Duckburg

Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s “Lemminkäinen’s Mother” (1897) shows a story from the Finnish national epic, “Kalevala,” in which “the warrior and womaniser Lemminkäinen dies because he has tried to kill the swan of Tuonela,” as the exhibition info says. Photo: Jouko Könönen/Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery

Audubon Gander-Kallela’s “Donald Duck’s Uncle” shows the artist’s “elemental avian romanticism and perceptive portraiture,” as the curators put it. The painting also shows subtle but readily detectable influences from Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s “Lemminkäinen’s Mother” – or is it the other way around? Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery/National Gallery of Duckburg

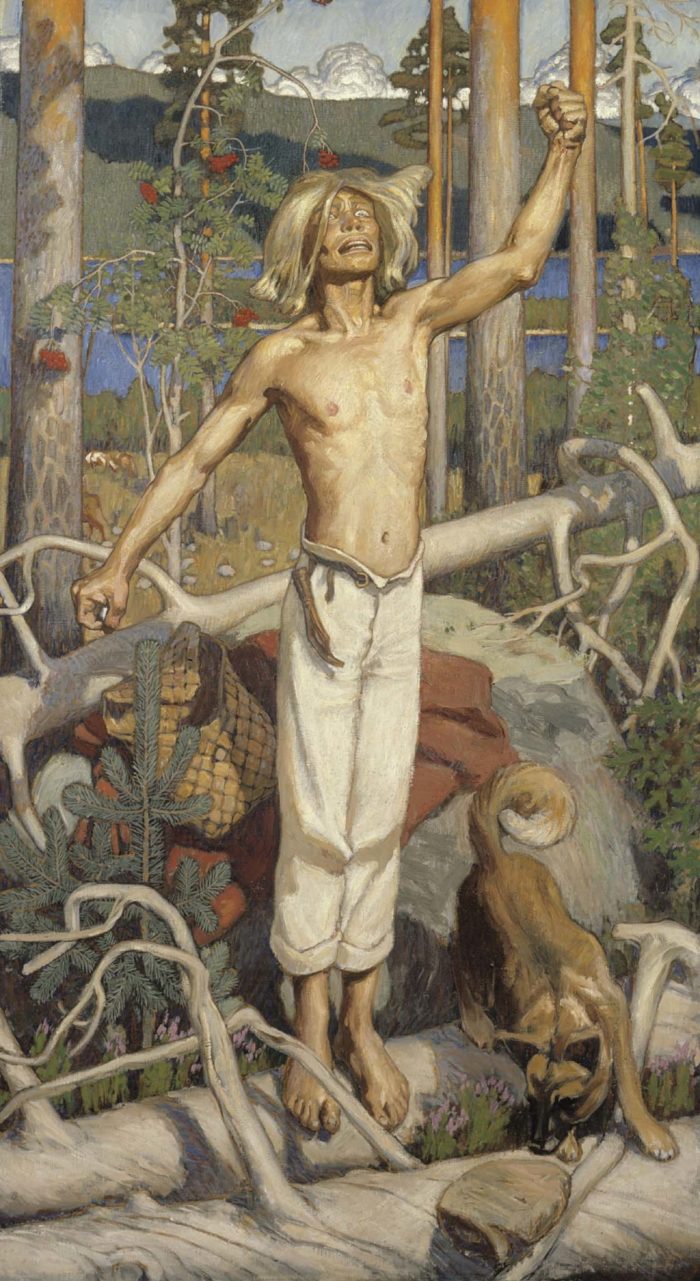

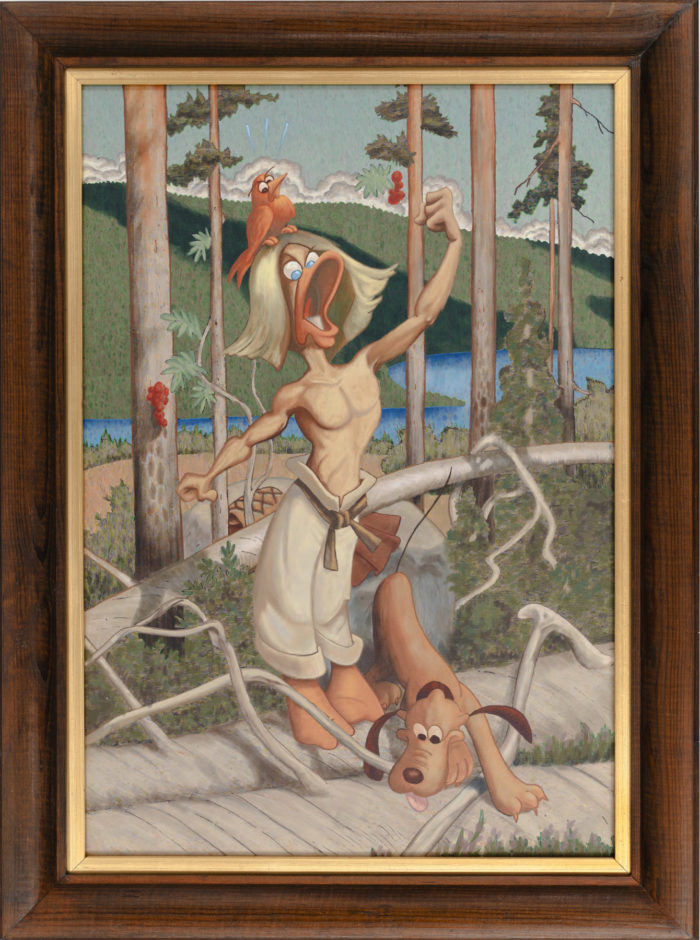

“Kullervo cursing,” painted in 1899 by Akseli Gallen-Kallela, recounts another “Kalevala” story: the slave Kullervo becomes enraged and sets out for revenge. Photo: Pirje Mykkänen/Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery

Audubon Gander-Kallela’s work “Kullervo’s Fowl Mood” is “inspired by the avian romantic ideal of primitive woodland as the cradle of Duckburgian culture” and depicts “a lone duck’s war cry in the battle with the wider world,” say the curators. Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery/National Gallery of Duckburg

Ferdinand von Wright’s “The Fighting Capercaillies” (1886), like many of the Finnish paintings echoed in the Duckburg exhibition, is one that most Finns immediately recognise. Photo: Yehia Eweis/Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery

“The Fighting Waterfowl,” by Ferdy von Wren, “presents an archetypal love triangle in a sylvan setting,” with cousins Donald Duck and Gladstone Gander courting the same maiden, and is “bursting with dramatic tension,” according to the wall placard. Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery/National Gallery of Duckburg

The dynamics of the Stories exhibition changed with the addition of Donald Duck characters. “Popular culture and high culture are constantly crossing paths,” says Ateneum chief curator Teijamari Jyrkkiö.

As she describes it, placing Duckburg within Stories highlighted “how our classics stay vital through the years; how other artists borrow from them, too; how popular culture makes use of works of fine art; and how dialogue is always going on.”

Mixing Donald Duck with Finnish classics is not as far-fetched as it may seem. Aku Ankka, as he’s called in Finnish, has achieved lasting strength and popularity stemming from the Aku Ankka comic book, which has been around since 1951. It is the most popular weekly publication in Finland, and also has a larger circulation than the country’s leading monthly consumer magazines.

Many Finns remember Aku Ankka as one of the first things they read by themselves, if not the first thing. “Teachers have been known to tell their pupils, ‘If you don’t read anything else, at least read Aku Ankka,’” says Jyrkkiö. Educators feel comfortable recommending the comic book because it maintains high language standards. Some stories are translated and some are Finnish originals, but all use impeccable, lively Finnish. They also often tie in with current events in Finnish society.

There you have it: An internationally famous American cartoon character known for speaking in incomprehensible quacks on screen paradoxically occupies a role as an enduring champion of written Finnish.

Youthful inspiration

Arvid Le Loon’s perceptive depiction of “Gus Goose at Work” shared the wall with other portraits and self-portraits at the Ateneum Art Museum.Photo: Peter Marten

When Aku Ankka editor-in-chief Aki Hyyppä tentatively approached Ateneum, the museum welcomed his suggestion: From a previous project, the comic book’s publisher possessed a couple Donald Duck versions of famous Finnish paintings – how about hanging them in Ateneum? Museum director Susanna Pettersson and her colleagues thought it was a great idea; they even commissioned additional pieces.

“Since the works refer to Finnish classics,” says Jyrkkiö, “we could put them in the galleries beside our own classic works, encouraging the public to compare the Duckburg art with our collection. That provided a new way of capturing the interest of children and young adults, and of anyone who doesn’t usually go to the museum but likes Donald Duck.”

The museum is always interested in getting more children, more families and more men to visit (women tend to outnumber men in the statistics).

The Duckburg show, which opened on October 3, 2017, proved a great success. From January to September of that year, Ateneum averaged 30,000 visitors a month, 4,400 of them children. For the month of October, the count was 48,393 visitors, 12,307 of them children. Over the duration of the exhibition, which lasted just less than five months, the museum received 245,688 visitors (almost 70 percent more than the pre-exhibition average), including 49,786 children.

The exhibition handout, a single sheet of thick paper, the size of a large postcard, listed the Duckburg artworks. It became a treasure hunt, especially good for all the kids. If one of the goals of art is to inspire reactions and conversation, Donald Duck’s presence at Ateneum brought many new voices to the discussion.

By Peter Marten, February 2018