Finnish divers and marine biologists are making exciting new discoveries during the first-ever detailed underwater survey of Finnish marine waters in the Baltic Sea (slideshow below).

The Baltic forms one of the world’s most polluted seas. The Finnish Inventory Programme for the Underwater Marine Environment, a ten-year programme known by its Finnish abbreviation, VELMU, aims to survey marine waters off Finland’s long and intricate coastline all the way from the Gulf of Finland through the beautiful island-dotted Archipelago Sea to the Bothnian Bay in the north.

Excess nutrients from agricultural fertilisers and other sources form the Baltic Sea’s largest problem, but hazardous chemicals can also be found. It is a shallow sea with a slow rate of water replacement via its one entrance to the Atlantic, the strait between Denmark and Sweden. Accurate information about marine life and seabed conditions in the Baltic Sea is urgently needed to ensure that its natural treasures can be protected.

“At the moment big gaps still exist in our maps of the ecology and geology of the Finnish waters of the Baltic,” says marine biologist Essi Keskinen, an experienced diver who is currently working on VELMU for Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services.

An eelpout seems to make eye contact with the camera. Photo: Mats Westerbom/Metsähallitus

“Diving for long periods in the Baltic can be hard physical work, especially with lots of heavy breathing gear and sampling equipment,” she says. “When we start diving in the spring after the sea-ice melts, the water temperature’s just two degrees Celsius. But I really love doing fieldwork at sea with other enthusiastic biologists and students. We usually make a base on a remote island where we might camp out for a week while diving in nearby waters.”

Submarine surprises

Beneath the waves the divers use pencils and plastic paper pads to note information on water depth, marine life and the ecological and geological features of the sea bed, which might be rocky, sandy, muddy, or covered with lush seaweed growth.

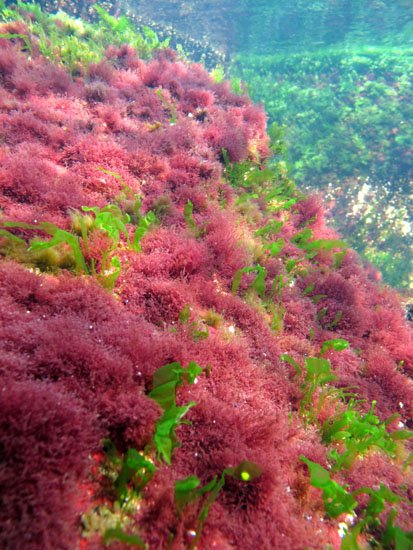

“We note marine plants, algae and any fish or smaller sea creatures that we see – as well as any pollution we might notice,” Keskinen says. “Unfortunately we find all kinds of rubbish underwater, from vodka bottles to car batteries, and even fridges. But it’s always exciting to explore new waters, and sometimes we find very beautiful underwater ecosystems with clear water and many colourful marine plants.”

Positive sea change under way

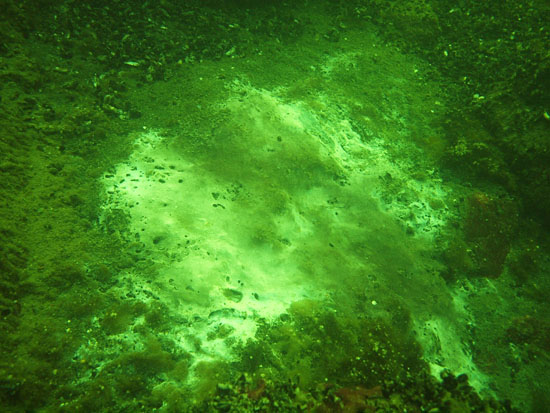

Although some parts of the Baltic can be clouded with algae, there are also areas of clear water and colourful plants.Photo: Mats Westerbom/Metsähallitus

Finland’s marine waters cover more than 50,000 square kilometres, and are up to 100 metres deep. “We can dive down to about 30 metres, but there isn’t much vegetation below ten or 20 metres because so little light penetrates,” says Keskinen. “Though we make wide use of drop videos and aerial surveys, we can’t possibly survey everywhere, so we use modelling to extrapolate data for areas we can’t visit.”

The inventory’s findings have resulted in detailed ecological maps of marine habitats in all Finnish waters. This information can be used to designate areas for conservation, or to control fishing, dredging and the locations of marine infrastructure such as pipelines and wind turbines.

The shallow and sensitive waters of the Baltic Sea have long suffered from pollution. But Keskinen, who has been diving in the Baltic for more than 20 years, is optimistic about the sea’s future prospects: “The situation’s still not good, but I think we’re past the worst of it,” she says. “In the late 1990s and early 2000s, some waters were like a thick porridge of blue-green algae. Measures like the new sewage treatment plants in St Petersburg and a ban on sewage releases from big passenger cruisers are slowly beginning to work.”