Everything started with a small act of mischief.

It was the late 1990s in Oulainen, a small town in the North Ostrobothnia region of Finland, when 12-year-old Päivi Kujanen decided to irritate her younger sister. Her sister played the five-string kantele, a traditional zither and Finland’s national instrument, which Päivi dismissed as unbearably dull.

One day, the girls’ uncle arrived with a find from a local auction: a large, 30-string kantele. Which sister would want to try it?

“I was about to say no when I realised that even a little tease counts,” Kujanen says with a laugh.

However, the instrument soon captivated her, and she couldn’t put it down.

“I had already become fascinated. It was something new, something different,” Kujanen says.

As the only kantele player in her home town, she found it easy and motivating to become the best. Once she received her first concert kantele and began proper lessons, the ambition crystallised.

“From the age of 15, my biggest dream was to become a kantele artist.”

Reinventing Finland’s national instrument

Video: Nina Karlsson and Annukka Pakarinen

Today, Kujanen, better known by her stage name Ida Elina, is one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary kantele music in Finland and abroad. Her signature electric kantele blends the delicate timbre of the instrument with the energy of modern pop and rock.

The kantele, or kannel, has a history stretching back more than 1,000 years. It features throughout Finnish folklore and the Kalevala, Finland’s and Karelia’s national epic, compiled in the 19th century, in which the hero Väinämöinen enchants listeners with the kantele’s sound.

“The kantele has an unusual tone which is a mix of guitar, harp, piano and a rich bass line,” Kujanen says. “It’s incredibly versatile.”

But finding her own sound took time. As a musically gifted child, she advanced quickly at first. The 30-string instrument opened an entirely new universe beyond the simple five-string.

“I had a strong preconception of the instrument. But the sound of the larger kantele stunned me. I thought, ‘Wow – you can make real music with this.’ It was a mind-blowing moment.”

A crisis, a turning point and Billie Jean

Päivi Kujanen has four custom-built concert kanteles with 40 strings and lever systems that allow swift key changes. Her kanteles are unique: there are no other kanteles like them in the world.

Kujanen’s path wavered when she failed to secure a place in the performance programme at the Sibelius Academy, Finland’s highest institute of music, named after the nation’s most famous composer, Jean Sibelius. Studying classical kantele in the music education department, she realised it wasn’t quite her world.

During an exchange year in Japan in 2009, she found the revelation she needed.

“I left Finland feeling lost. I even prayed that if something transformative happened in Japan, I’d continue playing. Otherwise, I’d quit.”

Living in Sapporo, she stumbled across a video of someone playing Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean on the kantele.

“I immediately thought, ‘Could you really play popular music on this instrument?’”

From that moment forward, she began forging her own path.

“Even my mum didn’t believe anything would come of it. Becoming an artist required enormous courage.”

New horizons: film scores and Finnish myth

Päivi Kujanen performs frequently in Finland but also internationally. She has been invited to appear at events such as Finland’s Independence Day reception, hosted by the President.

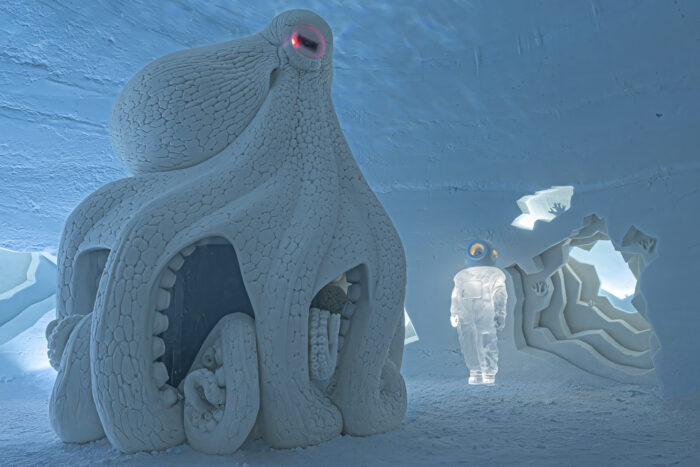

Today, Kujanen not only performs but composes extensively. Her recent major project, Under the Northern Skies, is a short film retelling the adventures of Lemminkäinen, a handsome and short-tempered young man from Finnish mythology.

“When I write songs, I often draw from my own life. But with this film, the inspiration naturally came from the Kalevala.”

Kujanen coproduced the film and composed its entire score, with the script constructed around her music. The film has travelled widely on the international festival circuit and collected a string of awards.

It feels particularly fitting, as the kantele occupies a central position in the Kalevala. And in Päivi Kujanen’s life, too.

By Emilia Kangasluoma, photos by Annukka Pakarinen, February 2026