In Fairbanks, Alaska, the day before Finland took over from the US as chair of the Arctic Council, teams of diplomats from the eight Arctic nations were still haggling over the wording of a key document. At two-year intervals the council holds a ministerial meeting in one of the member countries; the ministers of foreign affairs sign a declaration and formally pass the baton to the next nation to chair the council.

Such declarations contain more than just symbolic value. They provide a framework for the coming years, listing notes, concerns and affirmations in several categories: Arctic Ocean safety, security and stewardship; Improving economic and living conditions; Addressing the impacts of climate change; and Strengthening the Arctic Council. The declaration is also an essential reference for many organisations and working groups when they apply for funding.

This year, in light of statements the US president had made about his views of climate change and possible withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on climate change, several countries were apprehensive about challenges in reaching agreement on the declaration text. In the end, the Paris Agreement did make it onto the front page of the Fairbanks Declaration, although the wording could have been more forceful.

Several countries pointedly mentioned the Paris Agreement in their speeches the next day, May 11, 2017, at the publicly broadcast ministerial meeting chaired by US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. Finland noted that “The Paris climate agreement is the cornerstone for mitigating climate change.”

In addition to the eight Arctic Council member states (Finland, Canada, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the US), indigenous peoples also take part as permanent participants, including delegates from the Sámi (whose territory stretches across northern Finland, Norway and Sweden and the northwest corner of Russia), the Aleut, the Athabaskan, the Gwich’in, the Inuit and an association of the indigenous peoples of northern Russia.

These delegates emphasised that indigenous people possess local knowledge gained from centuries of experience and observation, allowing them to contribute in a valuable and necessary way that complements and strengthens the efforts of the “Western” participants. Judging by the applause and the content of various countries’ speeches, everyone in the room seemed to agree on this point.

No nation is an island

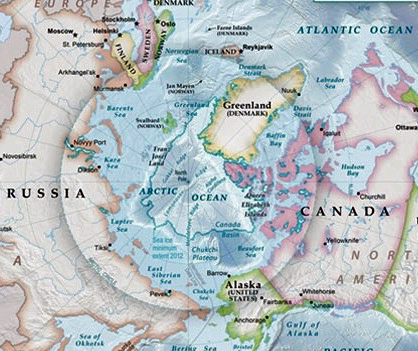

This circumpolar view of the Arctic provides a new perspective on the world.Illustration: Detail of map created by US State Department during the US Chairmanship of the Arctic Council (link to full version below).

With the big ministerial meeting in town, Fairbanks celebrated the Week of the Arctic with conferences, workshops and cultural events. The city feels like many Finnish cities, at least in the sense that it’s surrounded by woods, but different tree varieties dominate: shaggy black spruce with spindly trunks, and smooth, sturdy, white paper birch. The hills are much larger, and from some of them you can see the majestic mountains of the Alaska Range in the distance. Denali, North America’s highest peak at 6,190 metres (20,310 feet), is only about 250 kilometres (155 miles) away as the raven flies.

In this setting, Arctic Council working groups and other related organisations presented their most recent findings on protection of the marine environment; emergency preparedness and response; conservation of flora and fauna; sustainable development and more.

Although dealing with a direly urgent topic, the assembled diplomats, scientists, community leaders and researchers maintain a resolutely constructive, forward-looking attitude in the face of a sobering reality. Finland’s vision for its period as chair of the Arctic Council and beyond includes four priorities: environmental protection, connectivity, meteorological cooperation and education.

The experts at the Week of the Arctic emphasised repeatedly that humans must do everything possible to mitigate climate change – one of the simplest ideas could be to paint house roofs white to reflect sunlight. However, researchers are also evaluating methods of adapting. One of the Arctic Council working groups, the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), presented a new set of reports under the title Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic.

“Adaptation is absolutely needed, but there is also a need for us to reduce our greenhouse gases,” says Sarah Trainor of the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, who is one of the many coauthors. “I don’t want to talk about adaptation without putting that forward as well.”

Responding with resilience

The 2017 Arctic Council ministerial meeting in Fairbanks, Alaska opened with music and dancing by indigenous people from the region.Photo: Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Lehtikuva

AMAP’s multidisciplinary approach includes looking at economic, technical, demographic and political factors and investigating ways that governments, civil society, businesses and academics could increase their ability to adapt to change. “What are the issues that are really important?” asks Annika Nilsson of Stockholm Environment Institute, another coauthor. “It turns out it’s not just climate change, there are a lot of other issues going on that concern local municipalities and local planners.” In other words, you have to combine the small picture and the big picture.

Rafe Pomerance leads Arctic 21, a network of scientists and Arctic climate advocates. He uses the term unravelling when discussing the Arctic reality, because the word “pulls all the pieces together and describes the state of the Arctic with regard to climate change.” The signs are there in the sea ice, the snow cover, the permafrost, the Greenland ice sheet and other Arctic glaciers. “All the trends are in the same direction: melting, thawing, shrinking,” he says. And it is only accelerating.

Pomerance and other attendees have had lots of experience convincing people in non-Arctic regions that these issues are important to everyone on the planet. “The fate of Florida, the fate of coastal areas around the world, is tied up with the fate of the Arctic,” he says.

To paraphrase a thought expressed by a number of researchers and delegates at the Week of the Arctic: What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. It affects the whole globe.

By Peter Marten, May 2017