The year 2014 marked the centenary of Tove Jansson’s birthday. Her international fame stems from the Moomin adventures, which she wrote and illustrated, but there’s much more to her than that.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) led a remarkable life and remains one of Finland’s most beloved artists and authors. The immensely popular Moomins, although they are called trolls, actually possess surprisingly human traits. They are a curious group of creatures whose foibles and philosophising appeal to both kids and grown-ups.

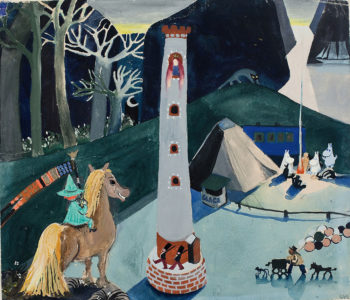

This detail from an early, undated Moomin illustration by Tove Jansson shows Snufkin on a horse (left) and the Moomin family around a campfire (at right, beside tent). Photo: Tampere Art Museum, © Moomin Characters

The characters first appeared in novels, then in comic strips and later in animated films. Jansson wrote the Moomin stories in Swedish, her native language and one of Finland’s official languages. The books stretch over four decades of her career, from the 1940s to ’70s. The first English translation was published in 1951 – several years before a Finnish-language version appeared.

A glance at the table of contents for Comet in Moominland, the first of the books to appear in English, provides a taste of the story’s swashbuckling adventures, humorous antics, philosophical insight and captivating cast of characters.

Here’s a sampling of the chapter descriptions: “Moomintroll and Sniff following a mysterious path to the sea,” “Moomintroll rescues the Snork Maiden from a poisonous bush,” “a fantastic crossing of the dried-up sea,” “a swarm of grass-hoppers,” “a coffee party” and, last but not least, “Chapter 12, which is about the end of the story.” The book’s settings include a cave, an underground river, an observatory and a party in the forest.

Beyond the Moomin books

Tove (left), shown here with her partner Tuulikki, spent most of each summer on an island off of southern Finland. The sea and the archipelago figure in many of her books.Photo: Per Olov Jansson/Moomin Characters

Many people don’t know that Jansson wrote novels and short stories for a grown-up audience, as well. Over the past several years, Sort Of Books has published these works in beautiful, new, English-language versions. Some of them are appearing in English for the first time ever.

In the introduction to Fair Play, Ali Smith says, “in her writing for adults Jansson was also, in her own quiet way, quite radical both with form and subject matter.” Jansson’s stylistic clarity “makes for mysterious transparency,” and her books describe “people not usually included or given that much space” in literature.

Fair Play forms a collection of autobiographical stories that relate parts of Jansson’s life with her partner Tuulikki. They were together for more than 40 years. Other Jansson books published under the Sort Of imprint include The Summer Book and Sculptor’s Daughter, both of which are considered classics, and four others.

Penguin released another Jansson-related book in December 2014, a new biography by Tuula Karjalainen entitled Tove Jansson: Work and Love (published in Finnish by Tammi as Tove Jansson – Tee työtä ja rakasta).

In addition to providing insight into Jansson’s versatile career as a writer and a visual artist, Karjalainen shows us how bold Jansson was in choosing her path in life. She lived with a man without being married – a scandalous development in those days. She also had relationships with women – these connections were open secrets in Helsinki at a time (the 1940s and ’50s) when such a relationship could still lead to jail or a mental hospital.

Paintings, murals and art circles

Detail from a self-portrait, “Lynx Boa” (1942).Photo: Finnish Nat’l Gallery/Yehia Eweis, © Tove Jansson Estate

Another side of Jansson unfamiliar to many Moomin fans is her painting career. Despite the eventual success of the Moomin books and her books for adults, Jansson herself considered painting her main professional calling for much of her life. During one phase of her career, Jansson supported herself by painting monumental wall murals for various government and corporate buildings.

Karjalainen says that Jansson was late in joining the wave of abstractionism that reached Finland in the 1950s, although she later produced fine work in that genre. In an interview for this article, Karjalainen suggests that Jansson did not take readily to abstractionism because she was “a storyteller by nature,” in painting as well as in literature.

In the less-than-open-minded art circles of mid-20th-century Helsinki, Jansson’s storytelling talent, success and versatility seem to have inspired some degree of jealousy. For much of the 1950s, she supported herself – and her other art – by writing and illustrating Moomin comic strips for England’s Evening News. “When she met artists [in Helsinki],” says Karjalainen, “she got a lot of negative feedback. It got so bad that she had to change her phone number because she’d get calls telling her that she’d sold her soul to commercialism.”

“It’s difficult for us to imagine today, but that’s the way it was.”

By Peter Marten, March 2014, updated September 2014