Linus Torvalds, a Finnish open source software engineer, has won the prestigious Millennium Technology Prize together with stem cell scientist Dr Shinya Yamanaka. Torvalds’ Linux operating system and Yamanaka’s stem cell research are both unparalleled and revolutionary in their respective fields.

The world’s most prestigious technology prize has been awarded to Torvalds in recognition of his work initiating the development of the open source operating system Linux kernel – used today by an estimated 30 million people worldwide.

Linux is the operating system behind most of our digital existence. Drawing cash from an ATM, watching a movie on board of a plane, or playing with your Android smartphone – all these devices have Linux at their core, making work and social life ever so much easier and more pleasurable. According to Torvalds himself, it all comes down to having “good taste” in visual planning and code. And the passion to give it all away for free.

Developing the Linux operating system has involved the equivalent of 73,000 person-years of work so far – most of it voluntary and unpaid. Linus Torvalds has worked around 21 years on the system himself. This award praises his achievements as having “significantly influenced not only the development of other major operating systems, but the online networking culture and ethical questioning as a whole, as well as the openness of the internet to everyone.”

Our article on Torvalds in 2000:

master programmer

Written by Patrick Humphreys

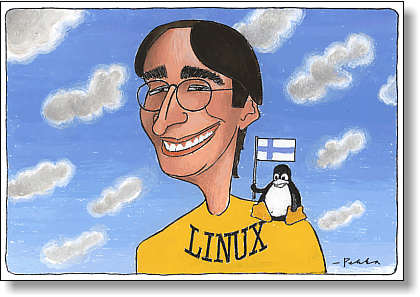

Drawing by Pekka Vuori

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

This year is turning out to be an extraordinary one for computing. Perhaps not a very enjoyable time for the richest man on the planet, Bill Gates, with his programs under virus attack and his Microsoft empire facing possible break-up. But all the better for the world’s best-known programmer, Linus Torvalds, who surely also bears the title of best-known Finn.

It’s hard to trump the achievement of writing a world-class computer operating system at the age of 21. Yet this year Torvalds was back in the headlines as one of the team that has produced a revolutionary new computer chip. And while the Linux operating system is a challenge to Microsoft’s Windows, the Crusoe chip could threaten the other computing giant, Intel.

The story of Linux is one of the great fables of computing, yet it begins as recently as 1991. That was when Linus Torvalds, a 21-year-old student at Helsinki University, decided to write his own computer operating system. Only a nerd would try; most folk buy their computers with the operating system already installed. And only a master nerd would succeed.

In some important respects, Torvalds’ Linux is better than the world’s principal operating system, Windows. It is more compact and it runs faster. It is also more stable, so it is preferred for use on the Internet, powering web servers that can be left unattended, without operatives to “turn off and then start again”, as Windows still so often requires.

The Love-letter virus that raced around the world at the start of May was another reminder of the dangers of dependence on Microsoft programs. It was designed to attack features of Windows and its popular e-mail application, Outlook. Linux users were unaffected. In the 1990s the world’s computing stock became a monoculture, like a forest with just one type of tree. Any disease can decimate it.

But Linux is not just another operating system. It is the outcome of a completely different philosophy, which has made its author into such a cult figure. Torvalds did not copyright his computer code so as to receive payment for his work. Instead, he published it on the Internet and invited other programmers to improve on it and to send their results back to him. By e-mail, of course.

Linux therefore was and remains a free program. Anyone can use it without charge, on condition that any improvements they make are also uncopyrighted and freely available. The nerds of the world took up Torvalds’ challenge. Of Linux today, only about 2% was written by the master himself, though he remains the ultimate authority on what new code and innovations are incorporated into it.

Again, the contrast with Windows is striking. How that system works is a proprietary Microsoft secret. An operating system is what controls a computer, but finding out how it does so is a lot harder than looking at the engine of a car. Computers translate everything into ones and zeroes. It is impossible to see what is happening from this digital stream.

Because the original quantities and instructions that make up Linux have been published, any programmer can see what it is doing, how it does it and, possibly, how it could do it better. Torvalds did not invent the concept of open programming but Linux is its first success story. Indeed, it probably could not have succeeded before the Internet had linked the disparate world of computing experts.

In making Linux an open language, Torvalds gave up the opportunity of growing rich from his work. This too is part of nerd culture, which thrives on the satisfaction of authorship and the respect of one’s peers rather than a portfolio of shares and a sports car in the drive. Today Torvalds lives in a rented bungalow though, admittedly, in California, where he moved in 1997 to work for a mysteriously secretive company called Transmeta.

The results of that project were unveiled in January this year, prompting some observers to suggest that the Finnish dragon-slayer was now taking on the world’s foremost chip manufacturer, Intel. Transmeta’s new Crusoe chips contain an array of computing tricks, allowing it to run programs intended for Intel processors but using a fraction of the power. For mobile devices this will be ideal. The first applications are expected this summer.

Linus Torvalds did not invent the Crusoe, of course, just as most of his Linux system was written by others. But this computing genius has quite a knack for being in the right place at the right time.

Original article by Patrick Humphreys, 2000

Foreword by Anna Leikkari, June 2012