Finnish children attend the same schools and classes regardless of their family’s background, wealth or culture. However, for one subject a week children are divided into groups: religion.

How can you teach religion in school when children come from increasingly diverse homes? Should society be responsible for providing children with instruction in religion? How can you guarantee fairness, equality and level of instruction?

These questions are being discussed in Finland and all over Europe. Just a few decades ago, nearly all Finns were members of the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Church, but a significant minority of today’s pupils are non-religious or belong to another religion. At the same time, the state’s relationship with the Evangelical Lutheran Church and, representing the traditional minority, the Finnish Orthodox Church, has dissolved and society has become secularised.

The relationship between education and religion incites strong feelings. When Finland’s Freedom of Religion Act was amended in 2003, the legislative process included extensive debate regarding teaching religion in school. Those holding fast to traditional values demanded the preservation of denominational religious instruction, whereas more radical elements felt that religious instruction should be eliminated altogether. The compromise resulted in the concept instruction in one’s own religion, which strives to guarantee the rights of minorities and to ensure that the child receives an education in accordance with their family’s convictions. Non-religious pupils study a subject called Life Perspective Studies, which includes ethics, worldview studies and comparative religion.

The Finnish compromise stems from the fact that teaching is not denominational, but rather respects the child’s personal background. Religion as a mandatory subject is still considered necessary, because it supports development of the child’s own identity and worldview, which also establishes a foundation for an intercultural dialogue. Because Finland has been homogeneously Evangelical Lutheran since the Reformation, it would be difficult to understand the country’s society and culture without knowing the history and thinking of the Lutheran Church.

Minority religion also taught in small groups

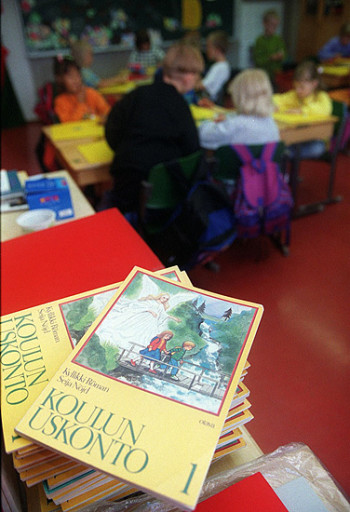

Religion textbooks such as these help children understand the cultural and human significance of religions.Photo: Sari Gustafsson/Lehtikuva

Religion is taught in comprehensive schools and upper secondary schools for one to two hours a week by the school’s own teachers or experts hired on a temporary basis. Minority-religion study groups are offered if there are at least three pupils of the same denomination in the school. Curricula for different religions are created jointly by religious communities and educational authorities. The Finnish educational establishment sets high qualification standards for teachers, and finding qualified teachers for minority religions has proven challenging.

The goal of a religious curriculum is to familiarise kids with their own religion and the Finnish traditions of belief, acquaint students with other religions and help them understand the cultural and human significance of religions. A key part of religious instruction is dealing with ethical issues in way that is appropriate to children.

In an average class approximately 94 percent of the pupils study Lutheran religion, 3 percent Life Perspective Studies and the remainder are divided into minority religions, such as Orthodox and Catholic study groups. In recent years schools in larger population centres have seen the advent of Islam study groups catering to children from immigrant backgrounds.

Sharing neighbours’ celebrations

In the Finnish system, teaching is not denominational, but rather respects the child’s personal background.Photo: Jussi Nukari/Lehtikuva

Even though studies show that both parents and teachers are primarily satisfied with religious instruction in schools, discussion on the matter is far from over. One challenge that has risen is how to initiate interaction between children representing different religions. When the same ethical issues are discussed in all religious curricula, is it possible for children to study them together?

Schools address the meeting of religions and traditions in celebrations held throughout the school year. How do children who do not celebrate Christmas at home participate in Christmas festivities? Do all pupils sing the traditional Finnish hymn at the school-leaving ceremony?

Bolder steps are taken in multicultural schools, where representatives of different religions hold traditional celebrations and invite everyone to attend. Sharing in the universal joy of celebration and learning about others’ traditions with an open mind poses no threat to any faith.

By Salla Korpela, April 2010