It was the summer of 1986, and Timo Rissanen was 11 years old. It was a confusing time to be growing up in a suburb in Finland. You could no longer just step into a grocery store and fill your basket without thinking twice. A catastrophic accident had just occurred at a nuclear power plant in Chernobyl, in what is now Ukraine, and a cloud from the explosion had travelled north, reaching Finland.

Families had to take precautions when it came to putting food on the table – many people remember the temporary ban on picking berries or mushrooms. For the first time, Rissanen realised that the environment wasn’t just an abstract concept, but rather it was the water that he consumed and the air that filled his lungs.

Fast-forward about a decade, and Rissanen was attending the University of Technology in Sydney, Australia, studying design with an emphasis on fashion and textiles. He was fascinated when his undergraduate professor, Julia Raath, brought up in a discussion on the high toxicity levels in textiles and dyes.

The link between fabric and environment

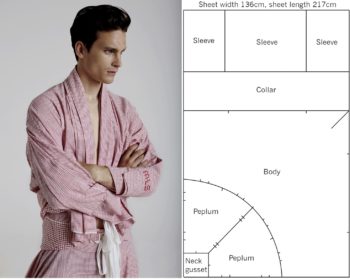

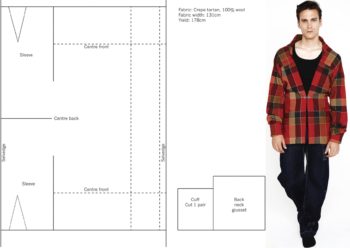

A model shows off zero waste pyjamas designed by Timo Rissanen. The pattern ensures that the fabric is used as efficiently as possible.Photo: Mariano Garcia; pattern: Timo Rissanen

Rissanen’s subsequent work experience as a high-end designer became the validation he needed to put Raath’s education into context and connect it with his childhood experience. “I noticed that a lot of textiles and fabrics used were imported from countries like Bangladesh, China and India because they don’t have regulations when it comes to the use of toxic chemicals in manufacturing processes,” he says. “This not only affects the labourers, but also consumers who wear these fabrics, and eventually the environment.”

He also remembers the startling levels of waste produced: “Almost 15 percent of handwoven fabrics worth 200 dollars a yard, from countries like India or Italy, would be thrown aside,” he says. What he saw as a clear relationship between the environment and fashion inspired his Ph.D. research (also in Sydney) on sustainable fashion and zero waste. In 2011 he started teaching at Parsons School of Design in New York, where he was the first professor hired to educate the coming generation of designers on these two concepts.

Fashion versus climate change

A pattern and a person display a zero waste cardigan by Timo Rissanen.Pattern: Timo Rissanen; photo: Mariano Garcia

Currently, Rissanen works closely on the curriculum, ensuring that all of the elective courses in the School of Fashion cover sustainability to a certain degree. His biggest contribution has been developing a core freshman course in 2013 called Sustainable Systems. The course aims at arming future designers with in-depth knowledge on fashion’s relationships with water, soil, the atmosphere and climate change. “My biggest takeaway from Timo’s class was the ability to critically think about the design process when constructing a garment,” says 22-year-old design student Jacob Olmedo.

His classmate Casey Barber says, “I had never approached design with questions such as, ‘How will this garment look after three to five washes?’ and ‘Will it maintain its shape and texture?’ Since learning from Timo I have continued to explore creative construction methods such as zero waste pattern making and sustainable sourcing of materials.” Olmedo and Barber will form part of the first graduating class to have taken Rissanen’s challenging freshman course.

Letting life flourish

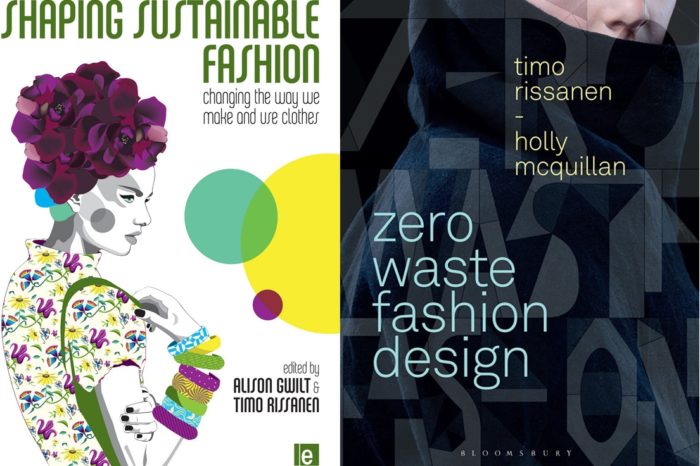

Rissanen’s career includes several book projects: He is one of the editors of “Shaping Sustainable Fashion” (Routledge, 2011) and one of the writers of “Zero Waste Fashion Design” (Bloomsbury, 2016).

Sustainable techniques are slowly being implemented within luxury brands, partly due to consumer awareness and pressure from organisations like Greenpeace, and also because massive profit margins allow them the ability to wean themselves off of toxic chemicals and hire trained labour. However, many popular high street brands still practice unsustainable, harmful techniques.

In addition, the current culture is one of fast consumption, where quantity takes precedence over the quality of the garments you own. It has been called the Instagram phenomenon, referring to the app where the lifespan of an image is two hours. It influences brands to constantly create new collections to appease consumers. “I know this is utterly depressing,” says Rissanen, but he is optimistic that within 20 years sustainable fashion and zero waste will “simply be good business practice.”

He’s continuing the good fight by training his future army of designers and taking his teachings beyond Parson. His projects have included co-curating the exhibition Yield: Making Fashion without Waste in 2011 and co-authoring the book Zero Waste Fashion Design (2016), both together with researcher and designer Holly McQuillan.

Rissanen believes that large-scale change starts on an individual level, and he has been gradually adopting sustainable techniques in his personal sphere: He brings his own grocery bags to the store, takes his food waste to a composting facility near his apartment in Queens, and makes his clothes last longer by avoiding use of a dryer. “Eventually, sustainability is the possibility that humans and other life can flourish on earth forever,” he says, quoting John R. Ehrenfeld, a scholar who co-authored the book Flourishing: A Frank Conversation about Sustainability (Stanford University Press, 2013) with Alfred J. Hoffman. “It’s simple in a way, but [it’s something] we can’t take for granted anymore.”

By Sholeen Damarwala, April 2017, updated May 2017