Finland holds elections for its 200-seat, single-chamber parliament every four years, coincidentally always the year before the US presidential election. This means that, as winter turns to spring and Finnish politicians are gearing up for an April election, American presidential hopefuls are announcing their candidacies.

While voters, and probably politicians too, may breathe a sigh of relief that election season lasts only a couple months in Finland, nobody is saying that Finnish politics is dull.

On March 8, 2019, with five weeks to go before the election, Prime Minister Juha Sipilä dissolved his conservative government coalition, citing its failure to get a long-debated social and healthcare reform approved.

Even without such chess moves, the election offers a wide field of parties and candidates, causing voters to pause for thought. Apart from paid advertising, rows of posters go up in public places several weeks before the election, with each one showing the candidates from a different party. In the capital, for instance, voters are taking stock of an array of 17 different posters.

Multiparty juggling act

Campaigning heats up as spring arrives, with just a few weeks to go before the election. Parties set up camp on town squares, such as this one in the eastern Finnish city of Joensuu, often right beside each other.Photo: Ismo Pekkarinen/Lehtikuva

Three groups that currently hold seats in Parliament are actually facing their first election. How is that possible? They all formed as breakaways during the previous term.

The so-called Blue Reform came into existence when 19 members of Parliament left the populist “Finns” Party, dissatisfied with the party’s choice of leader. Movement Now, created when well-known businessman and MP Harry Harkimo left the conservative National Coalition Party, is actually not a party, but a movement, as its name implies. Long-time political player Paavo Väyrynen formed something called the Seven Star Movement after being asked to leave the Citizens’ Party, which he himself had created after cutting ties with the Centre Party.

In addition to those mentioned above, parties in the outgoing Parliament include the Left Alliance, the Green League, the Social Democratic Party, the Swedish People’s Party of Finland and the Christian Democratic Party. The Feminist Party is on the ballot this year for the first time.

Sorting through the candidates

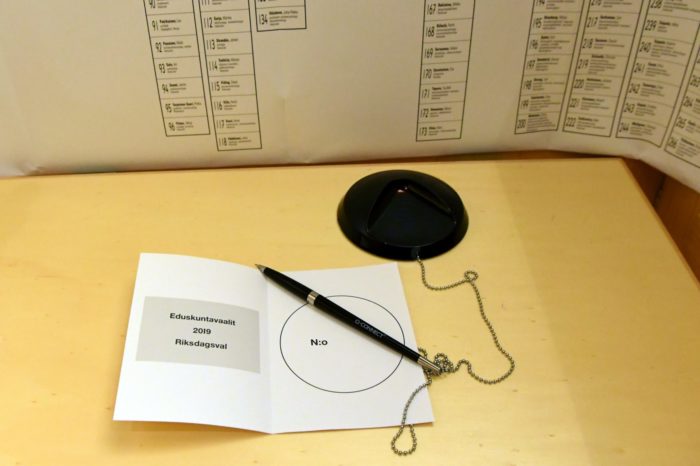

You write the number of your candidate on the inside of a folded card before placing it in the ballot box. Photo: Jussi Nukari/Lehtikuva

In a race where ten or 12 parties have a viable chance at winning seats in Parliament, what do you do if you can’t decide who to support? Some people try an election machine – not the same as a voting machine. For years, Finland’s largest daily, Helsingin Sanomat, and the Finnish national broadcaster Yle have each offered interactive online questionnaires to help voters narrow down their choices and seek information. Other media and organisations also publish their own versions, which may focus on a smaller set of issues or a certain region of the country.

Election machines have proved immensely popular. Yle offers its version, called the Election Compass, in English and Russian, in addition to the two official national languages Finnish and Swedish.

“Machine” might make it sound complicated, but it’s easy. The publishers solicit answers to a few dozen key questions from candidates ahead of time and feed the responses into the system. Then you go online and answer the same questions, clicking through the list.

Here are a few examples from the Yle site: Should Finland be a forerunner in the fight against climate change? Should the Finnish state encourage people to eat less meat using measures such as taxation? Should under-18s be allowed to undergo gender reassignment treatment? Should childcare leave be equally distributed between parents? Would NATO membership enhance Finland’s security? Should Helsinki introduce a traffic congestion surcharge during rush hour?

You can check who holds values and views that match your own, either question by question or in total. The results sometimes surprise users. Then you have the opportunity to click on those candidates and see their answers in greater depth.

Is this applying artificial intelligence to voting? Well, no, but it is a way to organise your thoughts and do some research before heading out to vote.

Show up and have your say

You go behind a screen to write down your vote in privacy.Photo: Markku Ulander/Lehtikuva

People do get out and vote. Voter turnout for the previous parliamentary election was a respectable 70.1 percent. All citizens 18 or over are automatically registered to vote and receive a notice in the mail before each election. Advance voting starts about two weeks before election day and accounts for almost half of the votes (46.1 percent of ballots cast in the 2015 parliamentary election happened during the advance voting period.)

Combine this with the Finnish proclivity for drinking coffee – the Finns drink more than ten kilograms per capita annually, the most in the world – and you have the makings of a tradition: election day coffee. People make voting into an outing by combining it with a stop at the local café. In fact, they used to get dressed up in their best clothes to go and vote. Folks are less formal nowadays, but the tradition of voting remains strong.

Parents may bring their kids with them to the polling place to get them interested, hoping the tradition will carry over to the next generation. The whole voting process takes a few minutes. You show your ID, they check your name off the list, and you receive a folded card. You go behind the screen and write the number of your candidate inside the card. Then they stamp the front of the card and you place it into a slot in a sealed box.

And that’s it. Afterwards you go for coffee with friends or family. The April weather may even be good enough to sit at an outdoor table. If you go the advance voting route, you can still go for coffee, no matter what day it is.

With so many parties, it’s highly unlikely that one of them could win outright. Usually the party with the most seats in Parliament bands together with several other parties to form a government coalition and get things done. For this reason, most voters select a party first and then a candidate. Even if that candidate doesn’t get in, the vote will still help that party gain seats.

More info about Finland’s parliamentary elections here.

By Peter Marten, April 2019