In 1809 Finland was annexed by the Russian Empire and became an autonomous Grand Duchy. Until then Finland had been an integral part of the Swedish realm for more than 600 years.

Finland’s destiny was sealed in Tilsit, in 1807, when Napoleon and the Russian Tsar Alexander I came to an agreement on their respective spheres of influence. Finland, situated in the Russian sphere, was conquered in the Finnish War of 1808–09.

Ehrenström’s city plan, 1820Drawing: Captain Anders Kocke

The cornerstone of modern Finland was laid in 1809 at the Porvoo Diet, where Tsar Alexander proclaimed himself constitutional ruler of the new Grand Duchy and promised to maintain the faith and laws of the land (Porvoo is located about 50 kilometres (about 30 miles) east of Helsinki). Historian Matti Klinge has pointed out that Sweden ceded a mere conglomerate of provinces to Russia; the Porvoo Diet united them as a state, “raised to the rank of nations.”

The creation of a capital was a clear indication of the Tsar’s will to make the new Grand Duchy a functioning entity. Under Swedish rule, the southwestern city of Turku (called Åbo in Swedish, which is still one of Finland’s official languages) had been the administrative and spiritual centre of Finland, but Stockholm had of course been its capital. In 1812 Alexander declared Helsinki – a small town of about 4,000 inhabitants – the capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland. In 1808 the town had been badly damaged by a fire in which one third of the residents had lost their homes.

This plaque on the wall of the university library terrace reminds passers-by of Ehrenström’s and Engel’s achievements.Photo: Matti Hurme

On the same day as Alexander declared Helsinki the new capital he appointed the military engineer Johan Albrecht Ehrenström, a former courtier of Sweden’s King Gustav III, head of the reconstruction committee. Ehrenström’s task was, in accordance with the wishes of Tsar Alexander, to rebuild the new capital in an unprecedentedly grand manner, “in order to show both Finns and the outside world that a new political unit, the Grand Duchy of Finland, had come into being,” as Klinge puts it.

In 1817 Ehrenström’s final town plan was ratified. Senate Square, bordered by a church and various administrative buildings, became the monumental centre of the plan. In the words of art historian Riitta Nikula, Ehrenström thus created “the symbolic heart of the Grand Duchy of Finland, where all the main institutions had an exact place dictated by their function in the hierarchy.” Ehrenström’s plan provided a fine outline for the construction of the new capital, but without a skilful architect the whole project could have faltered. Fortunately, he found one in Prussian-born Carl Ludvig Engel.

Carl Ludvig Engel and Senate Square

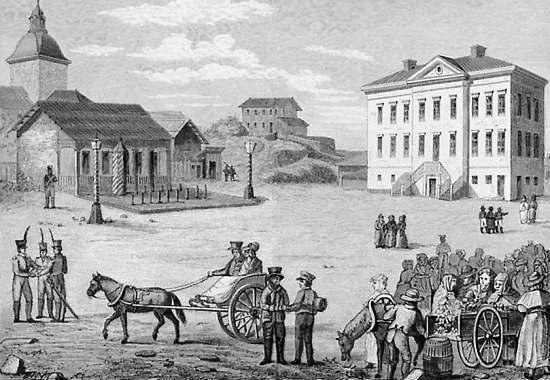

Senate Square in 1820© The National Library of Finland/Drawing: C.L. Engel

Carl Ludvig Engel (1778–1840), who had received his diploma in architecture from the Berlin Bauakademie in 1804, found no work in Prussia during the Napoleonic Wars. He applied for and received an appointment as city architect in Tallinn (Estonia). Soon he visited Finland and was asked to design an observatory for the Academy in Turku.

Ehrenström first met the talented young architect in 1814 and was immediately convinced that he had found the right man. After spending a couple of years in Saint Petersburg, Engel considered moving back to Berlin, but he was appointed architect of the reconstruction committee for Helsinki in 1816 and remained in Finland for the rest of his life.

Engel was thrilled by his new task: “Few architects have the good fortune to plan an entire city,” he explained in a letter to a friend. And Engel had every right to express himself this way; within a quarter of a century he had designed and completed about 30 public buildings in Helsinki, all in his chosen Neoclassical (Empire) style. Some of the buildings have been demolished, but his most important creations around Senate Square are preserved.

The first building to be completed was the main wing of the Senate (now the Palace of the Council of State) in 1822. The main University building, on the opposite side of Senate Square, was inaugurated in 1832. The general form of the building is similar to the Senate, but another expression can be found in the details. The University Library, completed in 1844 after Engel’s death, has often been praised as his most beautiful building.

No building task occupied Engel so long as the Lutheran church on the northern side of Senate Square. He worked on it from 1818 until his death in 1840. The Lutheran Cathedral, then called the Church of Nicholas, dominated the square and was finally consecrated twelve years later, in 1852. By the middle of the century, the new Empire-style Helsinki was finally ready. In his book Senate Square, professor Nils Erik Wickberg describes the result in the following way:

“It was a city in light colours – mainly yellow and grey – in which practically every building was in the same style, with the same kinds of cornices, window surroundings, pilasters and pediments and with the same low roof slope. There it lay, resplendently framed by sea inlets and bare masses of grey rock, which was later built on or converted into parks. When the distinguished poet, Bishop Frans Michael Franzén, who had moved to Sweden in the same year Ehrenström returned to Finland, visited Helsinki in 1840, he compared the city to a butterfly which has flown out of its cocoon and to Thebes charmed into place with the music of Amphion’s magic lyre.”

A demonstration against the Russian-imposed unlawful conscription, 1902. © National Board of Antiquities

People gathering in Senate Square during the general strike, 1905. © National Board of Antiquities

Nicolai Church, now known as Helsinki Cathedral, on a postcard from 1916. © National Board of Antiquities

Trooping the colour to commemorate the arrival of the White forces in Helsinki, late 1920s.

A view of Senate Square at the beginning of the 20th century. © National Board of Antiquities

A military parade, late 1920s. © National Board of Antiquities

A public ceremony on Senate Square, early 1930s. © National Board of Antiquities

New Year’s Eve celebration in the 1930s. Helsinki’s official Christmas tree is erected every year on Senate Square. © National Board of Antiquities

Fireworks on the 50th anniversary of Finland’s independence, December 6, 1967.

University students celebrating Independence Day, early 1970s. This is an ongoing tradition.

Ever since, the institutions responsible for guiding and governing the destiny of Finland have been located in the same buildings around Senate Square, and the square itself has been the venue of a great number of important gatherings and celebrations in the history of both the Grand Duchy and independent Finland. When, in the year 2000, Helsinki commemorated its 450th anniversary, the splendid Senate Square was a focal point for the celebrations.

By Frank Hellstén, June 2004