Taito Vesala, 96, has seen how blackboards have been replaced by tablet computers in Finnish classrooms. The skills of his descendants never cease to amaze him.

When Taito Vesala started school at the age of six in 1926 (all ages, dates and school years are correct as of the time this article was written, in late 2016), in the first year he had two weeks of school in the autumn and another two weeks in the spring, in an ambulatory school. After that, he attended four years of primary school, and there his education ended.

“Before we were given our school-leaving certificates, the teacher’s niece and I competed on who had the best grades in the class,” Taito recalls. “The teacher very much wanted me to continue to grammar school, since my grades were actually quite good. But my family was poor, so I had to go to work and give the money I earned to my parents.

“So that was the end of my formal education, and the rest of my learning took place in the school of life.”

In the 1920s, Finland was a poor, predominantly agricultural country, and had just recently become independent. Taito was the first one in his family to receive formal education.

When Taito’s great-grandson Tatu Vesala, 10, started school in 2013, he had a minimum of nine years of schooling ahead of him. Tatu, now in the fifth grade, enjoys going to school and dreams of becoming an actor.

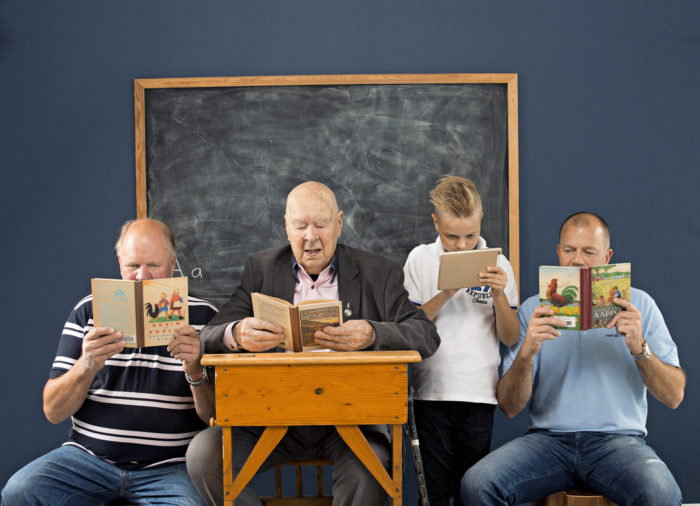

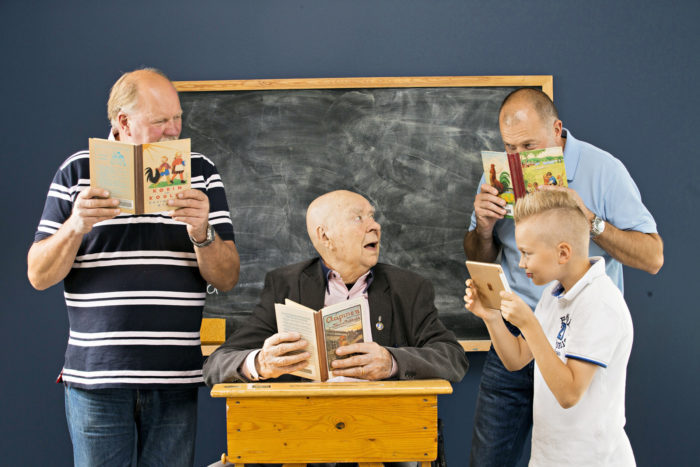

From left: Jarmo Vesala, Taito Vesala, Tatu Vesala and Jari Vesala share certain school experiences. Photo: Arto Wiikari

The development of the Finnish school system has coincided with the growing up of Taito’s descendants. Each generation has received more education than its predecessors. The Finnish education system has received recognition worldwide. In the PISA study, the joint research programme of the OECD member states, the skills of Finnish schoolchildren have frequently been ranked high.

International comparison of schools is difficult, but Finland’s good performance in tests is based on a few cornerstones. In Finland, the attitude towards education is positive and education is valued.

A 100-year journey

During the first years of the 20th century, only a third of rural children went to school. In the 1921 act on compulsory education, the objective was for all children to learn the primary school syllabus. After the fourth grade, the children who had the financial means and sufficient grades could apply to grammar school.

Despite his good grades, this opportunity was not within Taito’s reach. At the beginning of his career, he worked in a variety of jobs, ranging from police officer to real estate broker. The career path of his son Jarmo Vesala, 66, has been similar: he just retired from his job as a service station entrepreneur.

Jarmo’s education began in Helsinki in 1956. The Primary Schools Act was enacted two years after he started school, adding two compulsory study years. Jarmo’s education was that much longer than his father’s had been.

The Finnish school system was reformed almost completely in the 1970s, when the comprehensive school reform ended the era of the primary and grammar school system. The reform replaced the primary and grammar school system with the nine-year comprehensive school, which consisted of a six-year lower level and a three-year upper level.

The comprehensive school system was implemented in Finland gradually starting in 1972. This coincided with Jarmo’s son Jari Vesala starting school.

The comprehensive school reform was a hot topic at the time, but for Jari, the new school system was the way of learning.

“For me, the comprehensive school was the only option to receive education,” says Jari.

There is such a thing as a free lunch

Today, a free meal is served to all preschoolers, comprehensive school pupils and upper secondary level students on each of the five school days. Photo: Lehtikuva

One of the recipes for success in the Finnish school system is the school lunch. In 1948, the act on school meals was enacted, obligating municipalities to provide a free-of-charge lunch in schools on each of the then six school days.

“In the 1950s, the school meal service was very much like it is today,” Taito’s son Jarmo recalls. “At a certain time, we all got together to have lunch. I was taught at home that you had to finish all food on your plate.”

“A dish with a bad reputation in my school was meat stew with dill,” Jarmo says. “I was the only one in my class who was ever able to eat all of it.”

The years have gone by, and meat stew with dill is no longer on the school menu, which has kept up with the changing times and nutritional recommendations. Today, a free meal is served to all pupils on each of the five school days.

Tatu, a schoolgoer in the 2010s, is happy with the school meals served.

“Usually the food is quite OK,” says Tatu. “For example, I like ham and potato casserole. The food is tasty and good.”

Jari, an earth-moving contractor, is also among those who praise school meals.

“I have good memories of school meals. The food served in schools is still good – in fact, my father Jarmo and I go to a school located near our current earth-moving site to have lunch. The food is reasonably priced, healthy, and really tasty,” Jari says.

“I can’t help but admire how the school lunch room serves meals to 700 pupils on each school day,” says Jarmo.

Assessment without grades

Ever since the day when Taito was in school, the Finnish school system has used a grading scale of 4 to 10, with 10 being the highest grade, to assess pupils’ performance twice per year.

“I used to be a solid 7,” Jarmo says of his own school years.

Grades were given based on tests and classroom performance. The only oral test in the 1950s was the singing test, where each student had to stand in front of the class.

In recent years the grading system changed from numeric grading towards written assessments. Tatu’s assessment was given in letters up until now.

“For example, I got an A on the big German test last spring. My classroom conduct was a B, but proactiveness an A+,” the quick-witted boy explains.

Grandfather Jarmo admires Tatu’s aptitude for foreign languages. He himself did not learn any foreign languages in school.

“And here we have a ten-year-old who speaks both English and German,” exclaims Jarmo.

Tatu started learning German in fourth grade, and English started when he was halfway through second grade. The new core curriculum enables Tatu to start learning Swedish in sixth grade next year, so after six years in school, he will have studied three languages.

Versatile learning

Balancing the books: Nowadays kids study many school subjects that were not taught generations ago, and paper textbooks are becoming fewer.Photo: Arto Wiikari

The stories of four generations illustrate that while the basic principle of school has remained unchanged for nearly a century, the school system is also being constantly renewed. A big reform that will shuffle the Finnish school system in the coming years is the new core curriculum. In elementary school it took effect in autumn 2016.

In the recent years, phenomenon-based learning extending across different subjects has been introduced in schools. Tatu comes directly from school to meet us, from a class-organised travel fair. In the lessons, pupils plan and organise a travel fair, in which they present destinations and cultures of different countries to other classmates.

“This morning, Tatu left for school carrying our old suitcase, which is bigger than he is,” Jari says. The old suitcase is one of the props for the travel fair.

No more blackboards

Jarmo (left), Taito and Jari Vesala hold old-fashioned learn-to-read books, while ten-year-old Tatu uses a tablet.Photo: Arto Wiikari

New learning methods also have an impact on the school premises. As the pedagogic focus is shifting from collecting information to learning study skills, classrooms are transformed as well. Previously, the teacher’s desk was located between the pupils and a blackboard, and the pupils were seated in rows of desks. Today, school rooms are open and transformable. The teacher no longer lectures from a podium, due to the use of wireless computers and digitalisation.

Tatu’s classrooms no longer have blackboards or chalk. There is a digital camera on the teacher’s desk for displaying materials on a smart board. The teacher may also show videos from their computer. At times, the pupils also get to use tablets or computers.

“For example, when we colour or draw, we can use the tablet to look at models,” Tatu says.

Information retrieval skills are practised in connection with presentations, which the students give frequently in pairs or as a group.

Some of the textbooks are now completely electronic. Tatu’s elder brother Leevi Vesala, 14, has been assigned a tablet at school. The majority of learning materials are already electronic.

“Young people today are quite something,” says 96-year-old Taito.

“They receive so much information that I can’t help but admire their skills!”

By Hannele Tavi, ThisisFINLAND Magazine 2017