Metal shelving runs the length of the narrow room, stacked with grey boxes that hold decades of Nokia’s design experiments. The air is cool, the space tight and the hum of the climate system is the only sound.

Inside the boxes are objects that trace the evolution of early mobile technology – wood and foam models sanded by hand, engineering prototypes, colour samples, trend books and concept devices that never reached the market.

Michel Nader organises materials in the Nokia Design Archive, where researchers, students and fans can explore original designs. If anyone wants to access the archive, “they can easily send an email,” he says. “This is open, and then they can see it.”Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

This is the Nokia Design Archive at Aalto University, just west of Helsinki. I’m here with researcher Michel Nader and photojournalist Emilia Kangasluoma to see how the collection preserves both the objects and the stories behind them.

“These people were inventing their work,” Nader says. “There was no precedent to Nokia. Designers were hired to improve the shape of a phone, and eventually they were trendsetters.”

An unlikely rescue

The Nokia Design Archive is housed in the Väre building at Aalto University. In Finnish, väre refers to a ripple on water.Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

The Nokia Design Archive holds around 25,000 items, divided between this narrow room at Aalto and an extensive online collection covering more than two decades of design work.

None of it was guaranteed to survive. In 2017, professor Anna Valtonen, who had started the collection while working inside Nokia, received an unexpected call from a former colleague. As a result of Microsoft’s decision to shut down Nokia’s mobile device research and development operations in Finland, the archive’s materials were about to be thrown away, but there was still a chance to save them. (Microsoft acquired Nokia’s Devices & Services business in 2014.)

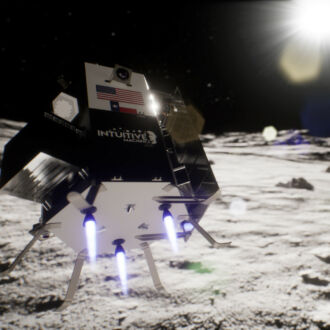

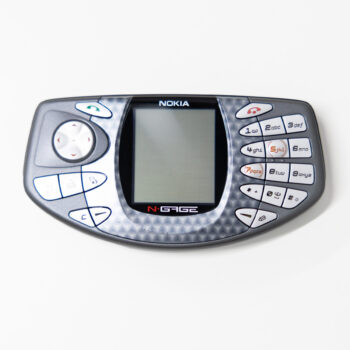

Nokia’s N-Gage, codenamed the Starship, set out to merge mobile phones with handheld gaming. Innovative but awkward to use, it became one of Nokia’s most memorable experiments – arriving a year before the Nintendo DS.Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

What followed has already become part of archive lore: a midnight call to Microsoft’s legal team in the US, an urgent scramble for permissions and, finally, a rescue mission to pick up what remained. “The lawyers went to talk to the US people in the middle of the night,” Nader says. “They got them to sign the contract in 24 hours, which was like a record thing.”

What survived was moved to Aalto and gradually rebuilt. The collection continues to grow as former designers contribute stories and context. “This lived experience adds to the archive,” says Nader.

The team that brought fashion to phones

Colour and material swatches like these gave Nokia designers a tactile guide, helping ensure that illustrations and prototypes matched the final look and feel of the phones.Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

The archive also preserves the unusual origin story of CMG (Colours, Materials and Graphics), the Nokia design team that helped change the look of mobile technology worldwide.

“CMG did not exist as a field,” Nader says. “At first it was one fashion designer hired in accessories – she was making pouches for phones. And she was like, ‘What if we make phones with colours?’, and she started painting them. The painted phones suddenly exploded and sold [best], so they started hiring more fashion designers and created the CMG team.”

A rare Nokia film prop designed for Minority Report. “Nokia was commissioned to design the futuristic gadgets featured in the movie,” says researcher Michel Nader. Only a few prototypes were ever produced.Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

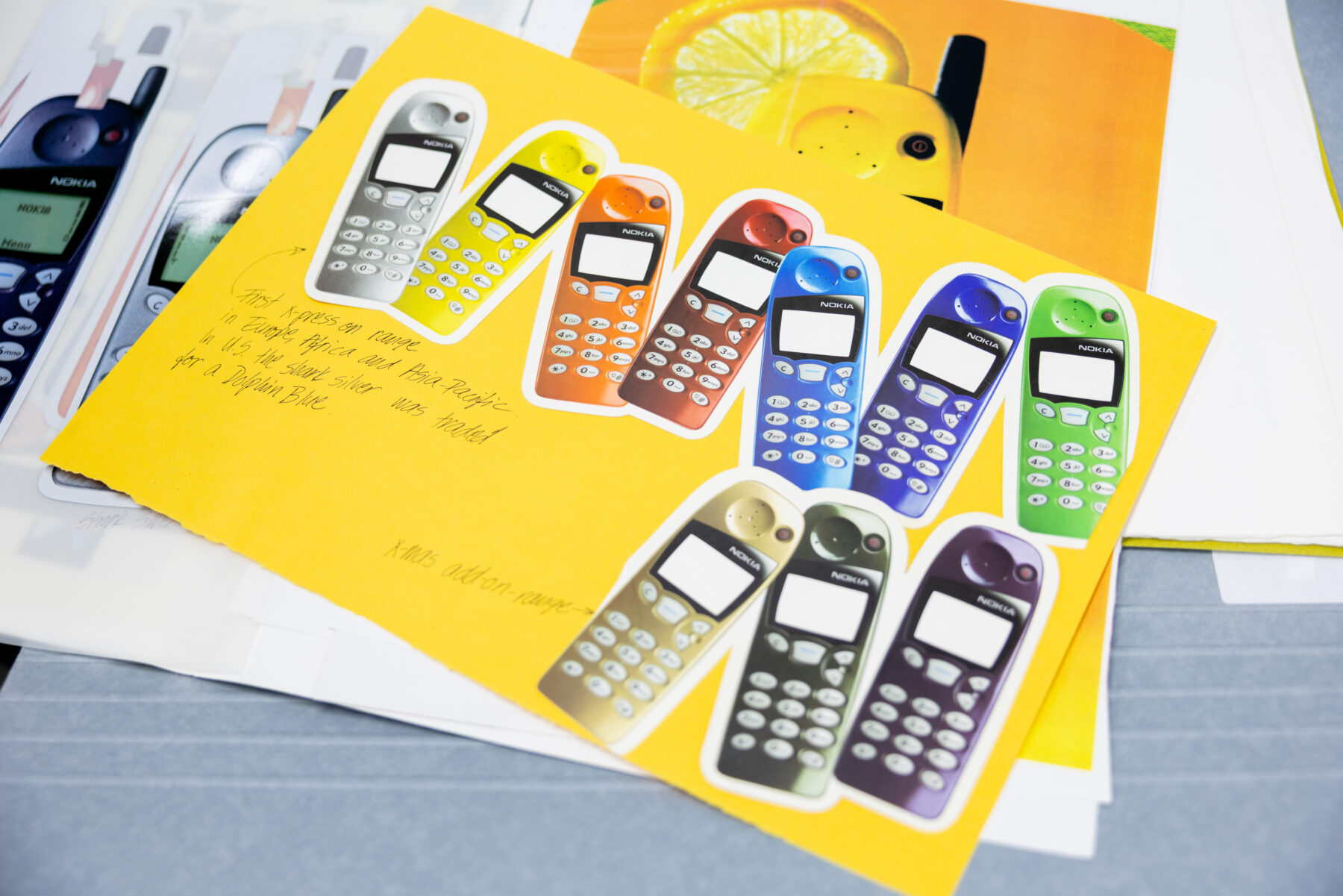

A glimpse into Nokia’s design process: a handcrafted presentation shows how designers combined technical specs with fashion-forward ideas. Released in 1998, the 5110 was one of the first phones with changeable covers.Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

What emerged was the world’s first fusion of fashion and telecommunications. Designers developed seasonal colour palettes, coordinated with factories across continents and shaped how millions of people experienced their mobile devices.

“They were invited to Paris [Fashion Week] to tell people the colours of the next season,” says Nader. “This was unique. This really didn’t happen anywhere else.”

The Moonraker: a smartwatch with a funeral

The Moonraker smartwatch, finished but never released.

Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

Nader opens a box to reveal a slim green smartwatch: Nokia’s Moonraker prototype. It was nearly finished when Microsoft cancelled the project after the acquisition. “That is a working prototype of the Moonraker,” Nader says. “They were planning for two years full-time and then it got pulled.”

In the digital archive, designer Apaar Tuli recalls the moment the team learned it was over: “The product was maybe two months from launch…The software was running. The hardware was close to the final build.”

Hundreds of devices had already been built and were boxed and ready. “When we heard the news, there was a bit of tears shed.”

To mark the loss, he took his team to the beach near the Nokia office in Espoo. “We wanted to do a little funeral party for our watch,” he says. “We sat there and discussed all the amazing experiences we had designing this product together. We kind of did a ceremonial funeral by burying it under the sand.”

It took months, he admits, before he could work on another device. “But Moonraker was definitely an amazing adventure,” Tuli says.

Design becomes a life’s work

Michel Nader connects with former Nokia designers, gathering their materials and stories for the archive. “I really do want a dumb phone though,” he admits with a smile.Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

At its peak, Nokia’s design organisation included hundreds of designers working across continents and time zones. The pace could be overwhelming. “One of the designers was telling me that they had, at some point, 75 projects on their desk at the same time,” Nader recalls. “And they only would produce maybe 10 to 20 percent.”

This prototype for Nokia’s Medallion II, part of the Imagewear series, blended mobile technology with fashion. It allowed wearers to display digital photos as jewellery-like accessories.Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

The intensity came with a price. “This was not a time when wellbeing was so important,” he says. “They dedicated their life to it. I had designers talking to me about how they had sleeping bags in the office. They had so much pressure.”

When Microsoft later shut down Nokia’s mobile phone operations, many designers struggled with the sudden loss. “One of the designers was talking about how he, for two years after leaving Nokia, couldn’t even work,” Nader says. “He was just destroyed. It was their family, but also everything.”

The human side of design

Codenamed Chameleon, Nokia’s 3210 introduced fully changeable covers, inspiring a huge third-party market. The customisation helped make it one of Nokia’s most recognisable phones.Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

As we step back into the daylight, the archive feels less like a collection of boxes and more like a record of lives shaped by design. The prototypes and interviews reveal the hopes, doubts, heartbreaks and breakthroughs behind devices that shaped how the world communicated.

And the influence didn’t end there. When the designers moved on, they carried their CMG training into other companies and classrooms, spreading the design approach that began at Nokia. The story continues through them, in the ideas and design cultures they continue to build.

By Tyler Walton, January 2026; photos by Emilia Kangasluoma