If we had to select three important dates from the whole of Finland’s political history, they could well be 1809, 1906 and 1917.

In 1809, after a period of more than 600 years, Finland ceased to be the easternmost part of the Kingdom of Sweden and was “elevated as a nation among nations” by becoming an autonomous grand duchy under the Russian tsar. In 1906, the traditional Diet of Four Estates was replaced by a democratic representative parliament characterised by universal and equal suffrage, universal eligibility and unicameralism. On 6 December 1917, Parliament (Eduskunta) proclaimed Finland an independent republic. Many of the structures of state had been created during the previous hundred years, if not earlier.

Today, Finland is a parliamentary democracy based on competition among political parties, power being divided among the highest organs of government. It does not in every respect fit into categories of parliamentarism constructed by political scientists. After some incremental changes in the 1990s, culminating in the constitutional reform of 2000, the elements of the Finnish parliamentary system are seeking and finding new roles that are tested and concretised in everyday politics.

Constitutional basis

The Finnish Constitution crystallizes the main principles of governance in very plain terms. Power in Finland is vested in the people, who are represented by deputies assembled in Parliament. Legislative power is exercised by Parliament, the President of the Republic having a minor role. The highest level of government of the state is the Council of State (the Government) which consists of a Prime Minister and a requisite number of ministers. Members of the Government shall have the confidence of the Parliament. Judicial power is vested in independent courts of law, at the highest level in the Supreme Court and the Supreme Administrative Court.

A distinctive feature of Finland’s Constitution is its rigidity. A constitutional law can be amended only if two-thirds of the members of Parliament agree. Two consecutive Parliaments have to adopt the changes. The same Parliament can amend a law if the amendment has previously been declared “urgent”. This calls for a five-sixths majority, which means agreement among at least four or five parties. In spite of this formal rigidity, there have been many incremental changes to the Constitution during the past twenty years. One aim has been to increase the flexibility of political decision-making. The price of this has been a weakening of the parliamentary opposition’s available options for manoeuvre.

Relations between Parliament, the Government and the President of the Republic are governed by the principles of European party-based parliamentarism. The Government must enjoy the support of a majority in Parliament, which elects the Prime Minister. The President traditionally has had considerable power in the area of foreign policy, although not as much or such undisputed power as his or her American or French counterparts. Under the constitutional reform of 2000, the President’s power in other political areas is limited; but the power to appoint senior civil servants does incorporate the potential for acts of political significance. The Government has to cooperate with both the President and Parliament, but when successful, this relationship strengthens the Government’s position in practical politics.

Parliament

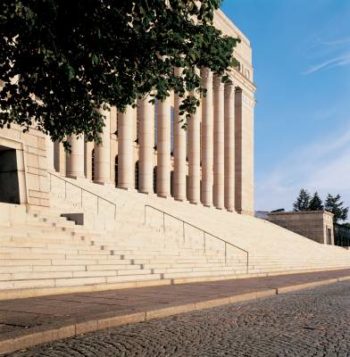

Situated on the main thoroughfare Mannerheimintie, the Parliament building is visible to anyone traversing downtown Helsinki by bus, train, tram or car.Photo: Joanna Moorhouse/Eduskunta

The history of the Finnish Parliament can be traced back to the 17th century, when the four estates of Finland were given the right to send their own representatives to the Swedish Riksdag of the Estates. At its birth in 1906, the Finnish Parliament (Eduskunta) was something of a rarity. It was unicameral and elected by universal suffrage, women included. Basically, the key elements of parliamentary organisation have remained unchanged for the past 100 years. In elections to choose the 200 Members of Parliament in recent years, about 70 percent of Finns over the age of 18, and eligible to vote, have done so. In the Parliament elected in 2011, no less than 85 of the members were women.

Parliament convenes – usually four times a week – for plenary sessions during which it debates matters, or rather makes speeches about them, and makes decisions by voting. MPs often put questions to members of the Government. It is unusual for an MP to vote against his or her party line. In principle, MPs have a free mandate; but in practice they have a party mandate, as in many other countries.

Much of an MP’s time is spent working in committees. The committees are preparatory bodies, usually comprising 17 MPs, through whose hands pass matters to be decided by Parliament. The committees regularly engage outside experts. The composition of the committees reflects the strength of each party in Parliament. As can be seen from the results of parliamentary elections, no single party is in a decisive position. Meetings of the parties’ own parliamentary groups are also important working forums for MPs.

Parliament has three main functions through which it represents the people and makes basic decisions on Finnish policy. It passes laws, it debates and approves the national budget and it supervises the way the country is governed.

Passing laws is a complicated process that usually begins with the Government placing a bill before Parliament, which it does some 200 to 300 times a year. Individual MPs may, and often do, propose legislation, but Government bills take preference and are better prepared. Parliament has no official machinery for making or preparing proposals. To be passed, a bill must have the support of a majority in Parliament and it must be signed by the President of the Republic. It takes about two to four months for a bill to be processed, in some cases even longer.

The national budget, presented to Parliament annually, is also prepared by the Government and much of the autumn period is devoted to debating it. Any changes made to the budget in Parliament tend to be marginal.

Parliament supervises the Government in many ways, both juridically and, in particular, politically. When a Government is being formed, Parliament has the vital role of electing a Prime Minister. When a new Government has been formed, it presents its political programme to Parliament. In accordance with a principle of classical parliamentarism, the Government must enjoy the confidence of a majority of MPs.

Every year, Parliament submits hundreds of written or oral questions to the Government or its individual ministers. Parliament may also test the degree of confidence enjoyed by the Government by making an interpellation. The result of the subsequent vote of confidence decides whether the Government may continue in office. Generally, the publicity attracted by such a move is greater than the risk to the Government. The risk last arose in the late 1950s, but this has not lessened the use of the interpellation.

Parliament also supervises the Bank of Finland, which is the central bank, and the Finnish Broadcasting Company, the country’s public service broadcaster.

Today, governments are predominately coalition governments with strong majorities. This allows them to be fairly confident that the MPs for the parties the governments represent will be loyal. Most ministers also act as MPs, which in turn allows them to participate in parliamentary voting.

Employers’ and labour organisations are not among the classical parliamentary players. In Finland, however, they often do have quite a noticeable – if not decisive – political role, particularly in issues concerning work and social security.

The Government and the President

The Government produces most of the material that Parliament deals with and uses as the basis for its decisions. The President formally appoints and dissolves the Government and he or she also suggests a candidate for Prime Minister, after negotiating with the parties in Parliament and consulting the Speaker of Parliament. In practice, the main role in the formation, functions and dissolution of the Government is played by the political parties involved.

If a Government resigns between parliamentary elections, the reason is usually disagreement among the Government parties that has come to light when the Government has had to make a difficult decision, or when its own bills are being dealt with by Parliament. After parliamentary elections the Government resigns. In recent years, from four to six parties have been represented in the Government and, in spite of their political heterogeneity, governments have been very stable.

The functions of ministers are extensive. They prepare the national budget and legislative reforms and, after obtaining the approval of Parliament and the President, implement the latter. The Government may also pass statutes if so authorised by Parliament. The ministers each direct their ministries with relative independence. There are 12 ministries, including the Prime Minister’s Office, and no more than 20 ministers. If an MP is appointed as a minister, he or she continues to work as an MP. Most ministers have this double role. It is normal practice that the leaders of the parties forming the Government, i.e. the party chairpersons, also act as ministers. But there are exceptions to this practice.

The main collective functions of the Government are sessions over which the President presides, ordinary sessions and evening sessions. The President attends only the first of these sessions, it being the highest level of the Government’s decision-making authority in legislative matters. An evening session is an informal occasion at which matters are prepared for discussion. It provides a useful opportunity for multi-party cabinets to try to reach agreement before actual decisions have to be made. There are also more limited preparatory ministerial committees; the most important of which handles all economic policy matters and could be regarded as the core of the Government. The President may attend meetings of the Cabinet Committee on Foreign and Security Policy.

The session presided over by the President is usually held on Fridays. Also present is the Attorney General, who oversees the legality of the procedures and decisions. At these sessions, the President formally makes his or her decisions on whether bills should be placed before Parliament or whether acts passed by Parliament should be signed. The President may go against the majority opinion of the Government. Similarly, he or she may refuse to sign a law passed by Parliament, in which case it does not come into effect. There is usually no visible conflict with the Government, however, because decisions are always well prepared and have gone through many stages. Finland’s presidents have refused to sign a law once a year on average. Moreover, Parliament may approve the same law again after it has been rejected by the President. If this happens, the law will come into effect without having been signed by the President.

The most important sanction open to the President in his or her relations with Parliament has been the right to dissolve Parliament and call new elections. This has happened seven times since 1917, and most recently in 1975. Under the constitutional reform of 1991, the President cannot dissolve Parliament if the Prime Minister has not made a proposal to that effect. Otherwise, interaction between the President and Parliament is limited to certain state ceremonies. For example, the President opens Parliament each year and declares Parliament closed at the end of an electoral period. Also, upon being elected, the President makes his or her solemn pledge of office before Parliament.

The Parties

Party leaders take part in a TV debate before the 2015 parliamentary election.Photo: Markku Ulander/Lehtikuva

During its approximately 100-year history, the Finnish political party system has been relatively stable. The historical background for the party divisions includes the ideal of nationality, the language issue (Swedish is a minority and official language), the socialist versus non-socialist divide, representation of the rural population, and the two-way division of the political Left. In Finland’s multiparty system, support for the parties runs approximately along the following lines: the three or four biggest parties each have around 20 percent of popular support and about ten smaller parties compete for the remainder – and half of them succeed in getting seats in Parliament.

In Parliament, it is essential for the parties to cooperate among themselves in the preparation of the budget and other legislation, but the representatives of the parties who are Government ministers are traditionally loyal to the Government’s line and the opposition parties do not normally form strong coalitions. Since the time when Finland became independent, the Centre Party (formerly the Agrarian Party) has been a kind of median party in government, being represented in almost all political governments.

Government coalitions may be large, and their compositions politically unconventional. For example, the largest right-wing party, the conservative National Coalition Party, was in government with two left-wing parties from 1995 to 2003; this was repeated in the Government formed in 2011. Also new parties have been added to the established system and have made their way into Government. For example, the small Finnish Rural Party (SMP), characterised by criticism against the “old parties”, was welcomed into the Government from 1983 to 1990 following its success in the elections. The Green League, which made its way into Parliament in 1987, was in the Government from 1995 to 2002 and from 2007 to 2011, and also in the Government formed in 2011. The populist “True Finns” party – the historical successor of the Finnish Rural Party – caught up with the three biggest parties in popularity in the 2011 elections. The “True Finns” participated in the coalition negotiations but decided to stay outside the new Government. After all, Finnish parliamentarism is nothing if not adaptable, pragmatic and absorbent.

From 1982 to 2012, all Presidents of the Republic came from the Social Democratic Party. Before that there had not been a single president of left-wing provenance. In 2000, Tarja Halonen became Finland’s first female president and served two six-year terms. In 2012, Sauli Niinistö of the moderate conservative National Coalition Party was elected president. He was re-elected in 2018.

Political parties elected to Parliament in 2023 (2019)

| Party | Seats | % of votes |

| National Coalition Party | 48 (38) | 20.8 (17.7) |

| “Finns” Party | 46 (39) | 20.1 (17.5) |

| Social Democratic Party of Finland | 43 (40) | 19.9 (17.0) |

| Centre Party of Finland | 23 (31) | 11.3 (13.8) |

| Green League | 13 (20) | 7.0 (11.5) |

| Left Alliance | 11 (16) | 7.1 (8.2) |

| Swedish People’s Party of Finland | 9 (9) | 4.3 (4.5) |

| Christian Democrats | 5 (5) | 4.2 (3.9) |

| Others | 2 (2) | 3.0 (2.9) |

Summary

In Finnish parliamentarism, the Government is the preparatory and executive body that produces material for Parliament to consider, approve or reject. The material is submitted to the President twice, but normally no conflicts arise between the President and the Government, or between the President and Parliament. A conflict between Parliament and the Government may lead to the Government’s fall. Since the 1980s, governments have been so strong that the opposition has had no way of toppling them. Constitutional reforms have strengthened progress towards majority parliamentarism. Indeed, governments usually sit for the whole of their four-year term. Parliament is highly dependent on the bills submitted to it by the Government. The Government has to report continually to Parliament in many ways on what it is doing and where it is going, but it controls the day-to-day political agenda.

Finland has been a member of the European Union since 1995. Membership has given Parliament and the Government new obligations and new roles, which every now and then revive the question of their relationship with the President, who leads the country’s foreign policy in cooperation with the Government. The Prime Minister’s role has become stronger along with the EU membership, plus the backing of constitutional reforms and long-lived governments. Through the Parliamentary Grand Committee, Parliament has access to EU matters being prepared by the Government, and any stand taken by the Grand Committee is politically binding on the Government.

In the type of party-based and consensus-oriented parliamentarism practised in Finland, political coalitions may be large and unconventional in composition. Interparty relationships may overshadow formal institutional ones. Decision-making requires the formation of coalitions and the acceptance of compromises. Nowadays, Finnish politics is characterised by pragmatism and a strong penchant towards consensus – factors that have not always been present. This situation limits the degree of freedom that parties have to articulate their ideologies or programmes and implement them.

Finnish parliamentarism is characterised by great flexibility, particularly in building coalitions to form the Government. This becomes evident before the elections in that the parties do not declare beforehand with which parties they are ready to form the Government. In practice, the Government is formed between those parties that can agree on a joint Government Programme. The Programme is more than a mere declaration presented to Parliament as a government statement at the beginning of the Government’s term in office. It is a plan of action containing objectives that the Government has determined it will achieve.

The political rhythm in Finland is set by parliamentary elections held every four years and presidential elections held every six years. Whereas even the new Constitution does not recognise the fact, parliamentarism receives some of its energy and dynamism from the ever-alert news media, from pressure groups and from the internationalisation of politics and the globalisation of the economy.

By Jarmo Laine, senior science counsel, Academy of Finland, April 2015, last edited June 2019