Heat radiates intensely. Deep rumbles and bangs echo through the air.

A glassblower gathers a small, glowing mass of molten glass from the furnace onto the tip of a blow pipe and lifts it into the air.

It seems as if the glass is dancing. With practiced precision, the glassblower blows, gathers more molten material, and blows again. The choreography is deeply ingrained in muscle memory.

Glassblowing requires finely tuned coordination between the eye and the hand. The artist must not only shape the material, but intuitively respond to its ever-changing nature.

A new glass object is being born.

Peek into any Finnish kitchen cabinet, and you’ll likely find iconic design pieces recognisable to almost any Finn. The playful, undulating edges of the Aalto vase, for example, embody Finland’s distinctive approach to glass.

How did this Nordic country come to be synonymous with glass artistry?

The beginnings of Finnish glassmaking

The Iittala glass factory is the only large-scale glassworks still operating in Finland. Smaller studios also continue the tradition in places such as Riihimäki, Nuutajärvi and Fiskars.

The journey to becoming a leader in global glass art took centuries of craft, persistence and innovation.

Finland’s glassmaking history dates back to 1681, when the first glass factory was established in Uusikaupunki, in southwestern Finland. Over time, new factories were established, while others were lost to fires or closures.

By the early 20th century, key players such as Iittala, Nuutajärvi and Riihimäki Glass had taken root in southern Finland.

Their early output largely focused on everyday utility glassware that was functional and well made, though stylistically similar and lacking distinction. At the time, Finland was rapidly developing its national identity, with design and artistic expression gaining momentum.

When Finland gained independence in 1917, it marked a turning point. Though Finnish glass design initially echoed international styles, the seeds of a distinct, homegrown aesthetic had already begun to grow.

By the 1930s, everything was about to change.

In the glass hut

Around 140 people work at the Iittala factory, including 45 glassblowers. Each handcrafted object is a team effort, supported by inspectors, finishers and skilled carpenters who shape custom tools and moulds.

Back inside the glass hot shop, the glassblower completes their work. A large, brownish lampshade emerges, perfectly formed.

A handler carefully inspects the piece before cutting it free. This one is a success, but not all pieces pass the test.

Mastering the art of glassblowing takes time, often a decade or more. Patience is as critical as skill in this demanding craft.

We’re in the village of Iittala, home to Finland’s only remaining operational glass factory. Here, thousands of glass objects are still made by hand each year.

The work is physically intense. The heat is unrelenting, and the process requires constant, deliberate motion.

“Rhythm is critical in glassblowing,” says Tuija Makkonen, Iittala’s brand manager. “Timing is everything.”

Makkonen and Jaana Eriksson, PR specialist at the Iittala Glass Museum, guide us through the glass hut and factory floor, offering insight into the intricate process.

Tuija Makkonen (left) and Jaana Eriksson describe glass as a very challenging material.

“Glass behaves differently every time,” Makkonen says. “Even the weather can affect it.”

Inside the glass hot shop, a dozen glassblowers are on shift, their movements synchronised like a well-rehearsed dance.

One pauses to wipe the sweat from their forehead before returning to work.

Only the most skilled artisans tackle the most complex creations, such as the iconic, irregularly curved Aalto vase.

The Aalto glass is born

The Aino Aalto series, from 1932, is the oldest collection that Iittala still has in production.

In 1932, the Karhula-Iittala glass factory launched a design competition calling for simple, practical objects. The competition marked the breakthrough of functionalism in utility glass.

Among the participants were the designer duo Aino and Alvar Aalto. Aino’s Bölgeblick glass, later renamed the Aino Aalto series, was one of the five winning entries. With its clean, concentric lines and timeless silhouette, it became a classic of pressed glassware and remains in production today. The series captures the Finnish ethos of blending beauty with everyday functionality.

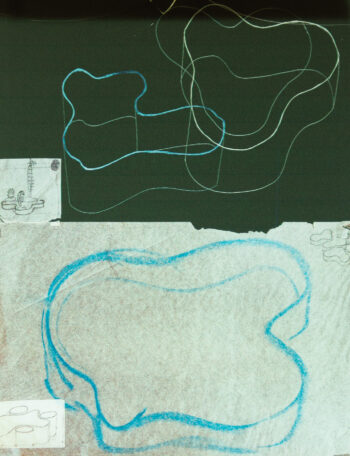

Alvar Aalto’s sketches show the vision behind his now-iconic vase. Each one takes up to 30 hours to complete, involving seven people and 12 production steps.

A few years later, Alvar Aalto entered another Karhula-Iittala competition with a body of work intriguingly titled Eskimo Woman’s Leather Trousers. The name may have raised eyebrows, but the design won acclaim. From that series emerged what would become one of the most iconic objects in Finnish design – the Aalto vase.

With its soft, undulating curves, the vase defied the rigid shapes typical of the era. Today, it is a fixture in Finnish homes and museums alike.

Glassware for every home

Designer Kaj Franck embodied the simple and understated style of 1950s Finnish design, blending minimalist aesthetics with everyday function.

The Second World War temporarily halted Finland’s promising progress in glass design. Scarcity of raw materials, price controls and strained international relations slowed production.

However, the post-war years saw a renewed drive for innovation. As the country rebuilt, so too did its design identity, now with even greater purpose. To thrive in a competitive global market, Finnish glass factories turned to a new generation of visionary designers: Timo Sarpaneva, Tapio Wirkkala and Kaj Franck.

These designers brought fresh ideas, emphasising simplicity and functionality even more. Franck, for example, championed the idea that glassware should suit every home.

His designs, like the stackable Kartio glasses, remain timeless staples, combining practicality with elegance. Similarly, Franck’s handleless pitchers symbolised 1950s design philosophy: affordable, space-saving and versatile.

This era marked a shift for Finnish glassware. It was no longer just for special occasions; it belonged in every home, for everyday use.

International recognition

Many Finnish glass art pieces draw inspiration from nature. Examples include Tapio Wirkkala’s design Kantarelli.Photo: Kaj Franck’s lecture slides /Aalto University Archives

The collaboration between designers and factories proved transformative. By the 1950s, Finnish glass design began garnering global attention.

Tapio Wirkkala’s Kantarelli vase, inspired by the delicate curves of the chanterelle mushroom, was a standout at a 1946 Nordic art exhibition in Stockholm, marking a turning point in Finland’s design story.

Soon after, Finnish designers began dominating the global stage. At the prestigious Triennale di Milano, Wirkkala, Franck and Sarpaneva won top honours, while contemporaries like Gunnel Nyman, Göran Hongell, Helena Tynell and Saara Hopea also brought home accolades. Finland had earned its place as a powerhouse of modern glass design.

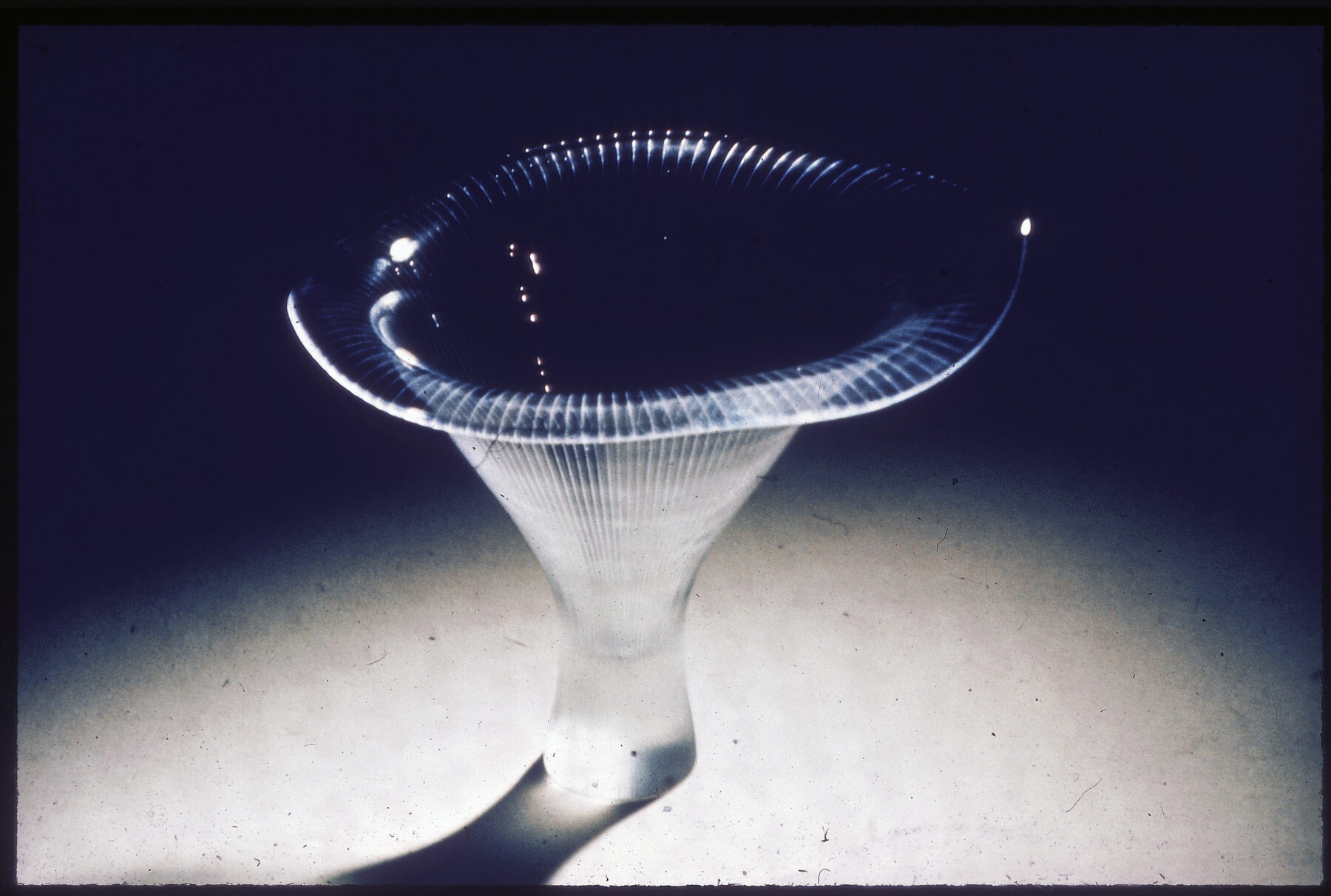

In 1954, Tapio Sarpaneva presented his iconic Orchid glass vase. Known for his versatility, he designed in glass, metal, wood, porcelain and textiles.Photo: U.A. Saarinen/Finnish Heritage Agency

In 1954, the American magazine House Beautiful named Sarpaneva’s Orchid glass vase the “Most Beautiful Design Object of the Year.” This clear-lined, minimalist vase remains celebrated as one of the world’s most beautiful objects.

By the mid-20th century, Finland had firmly established itself as a global design leader.

The evolution of glass art

Designer Tamara Aladin’s bold use of colour and form captured the playful spirit of the 1960s and 1970s.

While the 1950s saw designers drawing primarily from nature for inspiration, they began to push boundaries as the 1960s approached.

New techniques emerged, such as textured glass surfaces that played with light and shadow. Timo Sarpaneva’s Finlandia series, for example, used charred wooden moulds to imprint one-of-a-kind patterns onto molten glass.

Tapio Wirkkala continued to draw inspiration from the Nordic landscape. His iconic Ultima Thule series, with its icy, textured surface, echoed the beauty of melting snow and northern light, paying tribute to the stark beauty of Lapland, the northernmost region in Finland.

Oiva Toikka designed over 500 unique glass birds, beloved by collectors around the world. The Ruby Bird, pictured here, was made at the Iittala factory.Photo: The Museum of Central Finland

Meanwhile, young designers like Oiva Toikka began exploring more whimsical forms. His beloved series of colourful glass birds captured hearts in Finland and around the world.

Finnish glass today

At the Finnish Glass Museum in Riihimäki, visitors can view historic classics alongside contemporary works like Laura Laine’s Nude and Klaus Haapaniemi’s Vulpes.

While the Finnish glass industry has faced challenges in recent decades, with factories closing and traditional skills waning, the story is far from over.

In 2023, the Finnish glassblowing tradition was inscribed on Unesco’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity as part of a multinational project involving five other European countries.

This recognition affirms the cultural value of handmade glass and has sparked a renewed national interest in preserving and developing the craft.

The Finnish Glass Museum in Riihimäki showcases the work of contemporary artists such as Alma Jantunen (at left, 7 and 8), Aada Vainio (middle, 9), Paula Pääkkönen (bottom, 10), Tommi Toija (top, second from right, 11) and Arni Aromaa (top and middle right, 12 and 13).

Contemporary Finnish designers are building on this legacy with bold creativity.

Harri Koskinen’s glassware and lighting designs, Paula Pääkkönen’s glass ice lollies and Jasmin Anoschkin’s playful animal sculptures demonstrate the range and expressive power of modern Finnish glass.

Today, Finnish glass continues to be celebrated worldwide, featured in museums and sought after by collectors.

Jasmin Anoschkin is known for her expressive ceramic sculptures. In recent years, she has also embraced glass, using it to bring her imaginative, playful world to life.

“We’ve been fortunate to retain our reputation,” says Tuija Makkonen of Iittala. “Finnish glass remains synonymous with quality and creativity.”

Finland hosted the first Finnish Glass Biennale, a landmark event bringing together tradition and innovation, in summer 2025. With its next edition planned for 2027, it reflects the vibrant and evolving state of Finnish glass design – still glowing brightly, still inspiring.

By Emilia Kangasluoma, October 2025; photos by Emilia Kangasluoma unless otherwise noted

This article is partially based on information from Kaisa Koivisto and Uta Laurén’s book Suomalaisen lasin kultakausi (The Golden Age of Finnish Glass, Tammi, 2013) and Marianne Aav’s book Iittala: 125 years of Finnish glass – complete history with all designers (Design Museum, 2006).