Yes, of course there are Moomins. The characters that Finnish author and artist Tove Jansson (1914–2001) created are present wherever people display or discuss her work.

There’s also much more. You’re not a hardcore fan of Jansson or the Moomins until you’ve delved into her paintings. That’s exactly what the Helsinki Art Museum decided to do for an exhibition entitled Tove Jansson: Paradise (until April 6, 2025).

Viewing her murals and canvases and considering the time and circumstances of their creation, you get a sense of where Jansson’s life overlapped with her art.

City party, country party

Detail from Party in the City (1947) © Tove Jansson Estate. Photo: Hanna Kukorelli/Helsinki Art Museum

Detail from Party in the Countryside (1947) © Tove Jansson Estate. Photo: Hanna Kukorelli/Helsinki Art Museum

The museum’s wide-open upstairs gallery offers the perfect space for Paradise’s array of murals. Jansson painted numerous commissions between 1941 and 1956; during post-war reconstruction, artworks were in demand for public buildings.

(There are also two famous murals on permanent display at the Helsinki Art Museum: Party in the City and Party in the Countryside (both 1947). A Moomin is hiding in each one. Jansson painted herself among the partiers in City, as well as Vivica Bandler, with whom she had an affair.)

Fantastical scenes

Bird Blue (1953) © Tove Jansson Estate. Photo: Maija Toivanen/Helsinki Art Museum

Fairy-tale Panorama (1949, one of two panels) © Tove Jansson Estate. Photo: Maija Toivanen/Helsinki Art Museum

Murals and sketches of murals line the gallery walls. Several that could not be transported are present as full-size projections. Jansson painted for clients including schools, daycares, restaurants, a factory, a bank and a church.

People, animals, mystical creatures and, yes, Moomins appear, crossing landscapes of flowers, trees, bridges, mountains and rainbows by foot or on horseback. In more than one mural, a storm is brewing in the distance. One piece contains a cylindrical blue building very similar to the Moominhouse.

In the corner of Bird Blue (1953), painted for a school cafeteria, a kid has fallen asleep while reading a book. The rest of the fantastical scene may be the child’s dream vision.

Wind and water

Detail from Untitled (The History of Hamina) (1952) © Tove Jansson Estate. Photo: Maija Toivanen/Helsinki Art Museum

Detail from Story from the Bottom of the Sea (1952) © Tove Jansson Estate. Photo: Maija Toivanen/Helsinki Art Museum

Tove Jansson painted the surrealistic Fantasy in 1954 for a bank in Helsinki. © Tove Jansson Estate. Photo: Maija Toivanen/Helsinki Art Museum

For commissions such as a hotel in the harbour town of Hamina or a bank in Helsinki, Jansson depicted adult worlds that retain the allure of fairy tales and paradise while leaning towards the surreal.

In Untitled (The History of Hamina) (1952), naval officers chat with finely dressed women on a windy shore strewn with what might be detritus from a shipwreck. Far out to sea, a ship in full sail rides the waves as a dark cloud spews lightning. A tiny Moomin is visible – I won’t tell you where.

In the companion mural, Story from the Bottom of the Sea (1952), the same officers are standing on the ocean floor. One of them clutches a conch shell as various fish parade past. The men seem to be wondering whether to approach a mermaid who is lounging on the seabed.

A museum worker walked over to say that it would soon be closing time, but urged me to return the next day to watch a documentary film about Jansson painting a mural for the church in Teuva, a town in western Finland. I did.

Tough times in Teuva

Detail from Ten Virgins (1953)

© Tove Jansson Estate. Photo: Linus Lindholm

Teuva Church, built in 1953, replaced a church that had burned down in 1950. When architect Elsi Borg was planning the new building, she also wanted women to design the furnishings. Jansson created the altarpiece, a five-metre-long (16 feet) mural depicting the biblical story of the ten virgins – her only ecclesiastical commission.

The job stretched over several months, and conditions were tough. Cold air swirled in because the windows had not been installed yet. At times, Jansson wore multiple layers and a fur coat while working. However, this and other murals helped pay the mortgage on her downtown Helsinki studio and apartment, a wide, lofty turret with tall windows.

In the film, art historian and Tove Jansson biographer Tuula Karjalainen notes that, for all her skill and accomplishment, Jansson had to put up with male artists and many other people describing her efforts as mere “decorative art.” Meanwhile, murals by her male counterparts – many of them far less productive than Jansson – were “artworks.”

In 1953, Jansson also progressed with other projects, including her next Moomin book. During her time in Teuva that year, the region experienced heavy flooding. A flood happened in the very first Moomin book (The Moomins and the Great Flood, 1945), but the 1953 events may have directly inspired her reuse of the device in Moominsummer Madness (1954), in which a flood submerges Moominvalley.

The long shadow of war

Family (1942) © Tove Jansson Estate. Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery

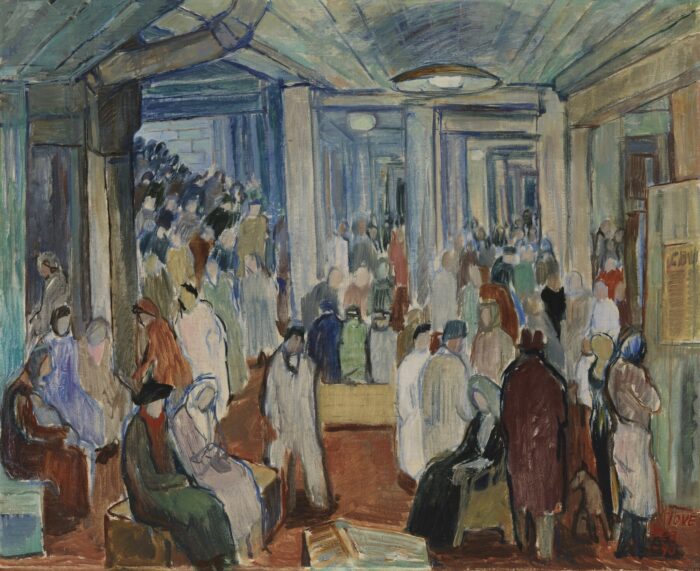

When the Alarm Goes Off (in the Keskuskatu Bomb Shelter) (1940) © Tove Jansson Estate. Photo: Yehia Eweis/Finnish National Gallery

In addition to the murals, the exhibition includes a large selection of Jansson’s other paintings – self-portraits, still-lifes and more.

When the Alarm Goes Off (In the Keskuskatu Bomb Shelter) (1940) shows a crowd of people in a cavernous underground space. Each has a dab of paint for a face, making them eerily featureless.

In Family (1942), we see Jansson herself standing in the middle, in dark clothing. Her mother is on one side and her father on the other, while her two younger brothers are in front of her, seated before a chessboard.

The Second World War hangs heavy over the sombre group. So do family dynamics, such as the stormy relationship between daughter and father.

The elder brother, Per Olov, 22 at the time, is in uniform – that very year he was serving at the front. Tove seems to be pointing at him. On a newspaper under the arm of Tove’s father, Viktor, we can just make out the words “Hitler,” “Nazi” and “Stuka” (a German military plane).

Tove, Per Olov and Viktor are all staring at different points in the distance, while Tove’s mother, Signe Hammarsten-Jansson, is looking towards her family – or perhaps past them. The youngest, Lars, has his eyes on the red and white chess pieces, some of them lying overturned on the table.

Tove is wearing a hat and gloves, and, behind her father, a door at the back of the room is half-open.

By Peter Marten, February 2025