A wren chirps in the alder grove. Biologist Aki Aintila pauses, his gaze instinctively drawn to the sound. He spots the small bird perched on a gnarled branch of an ancient tree.

Moments like these have defined his life, rooted in the centuries-old forest at Finland’s southernmost tip. This is Uddskatan Nature Reserve, a vital waypoint for hundreds of thousands of migratory birds each spring and autumn. At the heart of this natural crossroads stands the Hanko Bird Observatory, where Aintila and his team have spent decades studying migration patterns and uncovering how environmental changes reshape these journeys.

The path through the reserve leads to the red wooden walls of the Hanko Bird Observatory, situated on a rocky outcrop. The sea glistens in the sunlight as a chaffinch hops along the trail. Aintila’s face softens as he takes it all in.

“It feels like coming home,” he says.

The heart of the observatory

Near the bird station, there is also a sauna and a workspace for bird ringers.

The Hanko Bird Observatory, or Halias, was established in 1979 by the Helsinki region’s ornithological association, Tringa. The group purchased an old wooden cabin originally built in the 1920s by a fishing family. Today, it serves as a hub for groundbreaking bird monitoring and research.

Inside, the cabin is simple but functional: a small kitchen with essential appliances, a bedroom with three bunk beds and shelves lined with ornithological books. The lack of running water and reliance on a sauna for bathing underscore the rustic charm of the place.

At the Hanko Bird Observatory, spring monitoring lasts from early March to mid-June, while autumn monitoring runs from mid-July to mid-November.

In spring, the observatory sees more waterfowl unafraid of crossing the sea. In autumn, the focus shifts to landbirds and raptors arriving from the mainland.

Aintila pulls out some rye bread and cheese for lunch, and the door soon creaks open to admit Pekka Mäkelä, who has been ringing birds, and Juho Tirkkonen, a civil service worker. They immediately launch into a discussion about the day’s sightings – a common occurrence at Halias.

Aintila’s journey to this moment began in childhood when his grandfather subscribed to a wildlife magazine for him. One issue featured an article on birdwatching, accompanied by a stunning photo of a snowy owl.

“That’s how it began,” Aintila recalls.

His fascination with birds grew into a career in biology, and since 2019, he has been a part-time observer at Halias, spending more time in Hanko than at home in Helsinki.

Witnessing change in the skies

The nature trail to the bird station and its birdwatching tower runs north of Hanko’s outer harbour.

It’s time to climb the rocky outcrop and look out into the distance. Aintila leads us to an old fire control station from World War II, offering breathtaking scenery in every direction.

The sea laps gently, and in the distance, one can catch a faint glimpse of Bengtskär, the tallest lighthouse in the Nordics.

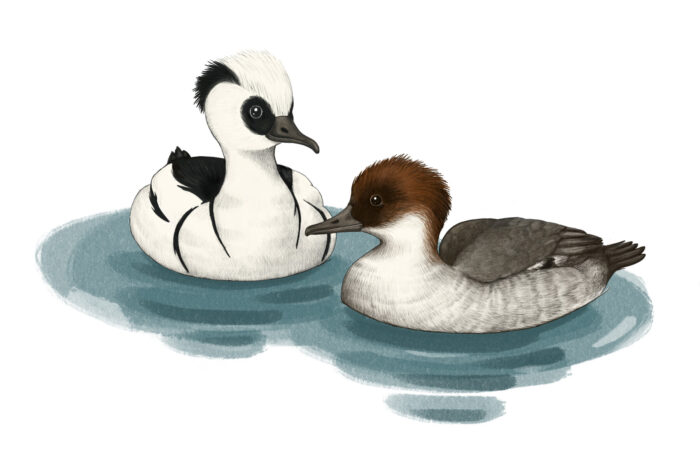

The sweeping views reveal eiders and long-tailed ducks floating on the sea, a white-tailed eagle soaring above and a smew paddling near the shore. These sights have become more than routine; they are data points in a larger story of change.

The migratory behavior of the smew (Mergellus albellus) has changed during the bird observatory’s monitoring period, as significantly more birds now winter on the Hanko Peninsula than before.

“Observations of smews at the bird observatory have increased by over 800 percent during the monitoring period,” Aintila explains.

Decades of standardised monitoring have revealed that warmer springs are causing many species to migrate earlier, while autumn migrations are sometimes delayed. This shift in timing, Aintila notes, is a profound disruption to ecosystems. Birds arriving too early may face fatal cold snaps, and their chances of survival and successful nesting diminish.

A legacy of observation

Finland is internationally known for its vast community of bird enthusiasts. Each year, approximately 700 active bird ringers tag over 200,000 birds in Finland.

Since the observatory’s founding, volunteers have conducted careful bird monitoring using standardised methods. Each morning before sunrise, regardless of the weather, someone climbs the fire control tower to count birds during the four-hour observation effort. Nets are opened for a five-hour ringing effort – a method where birds are gently caught, fitted with lightweight identification rings, and released – and species in nearby marine areas are also documented.

Some days are grueling: tens of thousands of birds may fly over Hanko in a single day, or thousands might need to be ringed.

Despite the challenges, Aintila recounts the awe of witnessing extraordinary migrations, like the autumn when over 220,000 finches passed through in a single day.

“I was on autopilot, just trying to process what my eyes were seeing and transfer it to paper. The shock hit me afterward,” he says.

The diversity of bird species in Hanko is remarkable. In late April, 112 different species were recorded in a single day near the station.

Sometimes, weather conditions for bird observation are so perfect that sleep becomes secondary to waiting for flocks to appear in the sky.

In 2023, Aintila experienced another unforgettable moment. Leading a group of young birdwatchers, he spotted a bird from eight kilometres away – a species never before seen in Hanko.

“I started shouting, ‘Gannet! Gannet! My god, there’s a gannet!’” he recalls with laughter.

Northern gannets are large seabirds known for their striking white plumage, black-tipped wings and dramatic plunge-diving. They’re typically found in the Atlantic, making their appearance in the Baltic a rare and thrilling surprise.

The bird stayed in view long enough for everyone to marvel at it before disappearing over the horizon.

“It was incredible,” he says, still trembling at the memory.

Fragile ecosystems, unwavering dedication

The robin (Erithacus rubecula) is a thriving bird species in Finland. It migrates to Finland each spring from Southern Europe.

Walking through the coastal forest toward the sandy spit of Gåsörsudden, Aintila points out a robin with a striking orange chest and a wheatear perched on a rock. His observational skills have honed over decades.

For Aintila, birdwatching combines discovery and the joy of realisation.

“These are universal aspects of birding and seem to satisfy some primal hunter-gatherer instinct,” Aintila explains.

He reflects on the interconnectedness of ecosystems. Birds are more than a fascination; they are indicators of environmental health. A bird arriving at the wrong time can disrupt entire food chains.

“Every observation contributes to understanding these shifts,” he says, lifting his binoculars to scan the horizon.

At the tip of the peninsula, an oystercatcher pair stands near the water. Aintila notes that the oldest ringed oystercatcher in Europe lived over 40 years. How much of the world might such a small bird have seen?

A shelduck swims at the tip of the sandbank. A common tern flits low over the water. It’s comforting to know that while society and technology evolve, bird observation in Hanko has remained consistent since the 1970s. Traditional methods are still the most suitable.

Aki Aintila first visited the Hanko Bird Observatory in the early 2000s.

A raven croaks in the distance, and Aintila smiles.

It’s time to head back.

Text and photos by Emilia Kangasluoma, May 2025

Illustrations by Eveliina Rummukainen