We’ll run through the main events in Finnish history. Broadly speaking, it can be divided into three chapters: the Swedish period prior to 1809, the Russian period from 1809 to 1917, and the independent period from 1917 to the present day.

Until the middle of the 12th century, the geographical area that is now Finland was a political vacuum, though interesting to both its western neighbour Sweden and the Catholic Church there, and its eastern neighbour Novgorod (Russia) and its Greek Orthodox Church.

Sweden came out on top, as the peace treaty of 1323 between Sweden and Novgorod assigned only eastern Finland to Novgorod. The western and southern parts of Finland were tied to Sweden and the Western European cultural sphere, while eastern Finland, i.e. Karelia, became part of the Russo-Byzantine world.

The Swedish reign

As a consequence of Swedish domination, the Swedish legal and social systems took root in Finland. Feudalism was not part of this system and the Finnish peasants were never serfs; they always retained their personal freedom. Finland’s most important centre was the town of Turku, founded in the middle of the 13th century. It was also the Bishop’s seat.

Turku Castle is Finland’s oldest medieval castle. Construction began in the 13th century and was completed in the late 16th century. © Visit Finland

The Reformation started by Luther in the early 16th century also reached Sweden and Finland, and the Catholic Church consequently lost out to the Lutheran faith.

The Reformation set in motion a great rise in Finnish-language culture. The New Testament was translated into Finnish in 1548 by the Bishop of Turku, Mikael Agricola (1510–1557), who brought the Reformation to Finland and created written Finnish. The entire Bible appeared in Finnish in 1642.

During its period as a great power (1617–1721), Sweden extended its realm around the Baltic and managed, due to the weakness of Russia, to push the Finnish border further east. With consolidation of the administration in Stockholm, uniform Swedish rule was extended to Finland in the 17th century. Swedes were often appointed to high offices in Finland, which strengthened the position of the Swedish language there.

Finland as a Grand Duchy of Russia

When Sweden lost its position as a great power in the early 18th century, Russian pressure on Finland increased, and Russia conquered Finland in the 1808–1809 war with Sweden.

During the Swedish period, Finland was merely a group of provinces and not a national entity. It was governed from Stockholm, the capital of the Finnish provinces at that time. But when Finland was joined to Russia in 1809 it became an autonomous Grand Duchy. The Grand Duke was the Russian Emperor, whose representative in Finland was the Governor General.

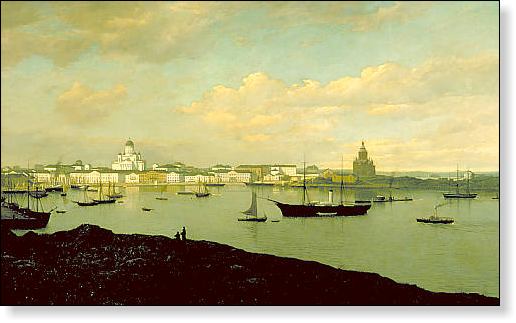

A view of Helsinki from the late 19th century, by Oscar Kleineh (1846–1919).

Finland’s highest governing body was the Senate, whose members were Finns. Matters pertaining to Finland were presented to the Emperor in St Petersburg by the Finnish Minister Secretary of State. This meant that the administration of Finland was handled directly by the Emperor and the Russian authorities were therefore unable to interfere.

The enlightened Russian Emperor Alexander I, who was Grand Duke of Finland from 1809 to 1825, gave Finland extensive autonomy thereby creating the Finnish state. In 1812, Helsinki was made the capital of Finland, and the university, which had been founded in Turku in 1640, was moved to Helsinki in 1828.

The Finnish national movement gained momentum during the Russian period. The Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, created by Elias Lönnrot, was published in 1835.

The Language Decree issued in 1863 by Alexander II marked the beginning of the process through which Finnish became an official administrative language. Although only one-seventh of the Finnish population spoke Swedish as its first language, Swedish retained its dominant position until the beginning of the 20th century.

The Finnish Diet was convened in 1863 after a break of more than half a century. From then on, the Diet met regularly, and active legislative work in Finland began. The Conscription Act of 1878 gave Finland an army of its own.

The obliteration of “Finnish separatism,” a policy also known as Russification, started during the “first era of oppression” (1899–1905) and continued during the second era (1909–1917). The 1905 Revolution in Russia gave Finland a short breathing spell, while a new legislative body to replace the old Estates was created in 1906. At that time this was the most radical parliamentary reform in Europe, because Finland moved in one bound from a four estate diet to a unicameral parliament and universal suffrage. Finnish women were the first in Europe to gain the right to vote in parliamentary elections.

The independent republic

On December 6, 1917, Parliament approved the declaration of independence drawn up by the Senate under the leadership of P.E. Svinhufvud (1861–1944).

At the same time, the breach between the parties of the left and the right had become irreconcilable. At the end of January 1918, the left-wing parties staged a coup, and the government was forced to flee Helsinki. The ensuing Civil War ended in May with victory for the government troops, led by General Gustaf Mannerheim (1867–1951). Finland became a republic in the summer of 1919, and K.J. Ståhlberg (1865–1952) was elected the first president.

The independent republic developed briskly during the 1920s. The wounds sustained in the Civil War were alleviated by conciliatory measures such as including the Social Democrats in the government; in 1926–1927 they formed a minority government on their own.

Although Finland first pursued a foreign policy based on cooperation with Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland, the League of Nations was already the cornerstone of Finnish security policy in the 1920s. When the inability of the League of Nations to safeguard world peace became evident in the 1930s, Parliament approved a Scandinavian orientation in 1935.

In the Winter War Finland stood alone; other countries offered only sympathy and modest assistance. Finnish ski troops inflicted heavy casualties on the Russian army. Finland’s survival against overwhelming Russian forces became legendary all over the world. © SA-kuva

In August 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a nonaggression pact, which included a secret protocol relegating Finland to the Soviet sphere of interest. When Finland refused to allow the Soviet Union to build military bases on its territory, the latter revoked the nonaggression pact of 1932 and attacked Finland on November 30, 1939. The “Winter War” ended in a peace treaty drawn up in Moscow on March 13, 1940, giving southeastern Finland to the Soviet Union.

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, Finland entered the war as a cobelligerent with Germany. The “Continuation War” ended in armistice in September 1944. In addition to the areas already lost to Russia, Finland also ceded Petsamo on the Arctic Ocean. The terms of the armistice were confirmed in the Paris Peace Treaty of 1947.

Marshal Mannerheim was made president of the republic towards the end of the war. He was succeeded in 1946 by J. K. Paasikivi (1870–1956), whose aim was to improve relations with the Soviet Union.

The Olympic Games were held in Helsinki in 1952, and in 1955 Finland joined both the United Nations and the Nordic Council. Among the major achievements of Nordic cooperation were the establishment of a joint Nordic labour market in 1954 and a passport union in 1957.

Urho Kekkonen, who was elected president in 1956, worked to increase Finland’s latitude in foreign policy by pursuing an active policy of neutrality. This was evident for instance in initiatives taken by Finland, such as the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe held in Helsinki in summer 1975.

Kekkonen led Finland for a quarter of a century before resigning because of poor health. Mauno Koivisto was elected president in 1982.

Recent history

Spring 1987 marked a turning point in the government, when the conservative National Coalition Party and the Social Democrats formed a majority government that remained in power until 1991. After the 1991 election, the Social Democrats were left in opposition, and a new government was formed by the Conservatives and the Centre Party (formerly the Agrarian Party).

The upheaval that took place at the end of the 1980s and early 1990s, including the dissolution of the Soviet Union, was evident in Finland in both a liberalised intellectual atmosphere and in greater latitude in foreign policy. Finland recognised Russia’s position as the successor to the Soviet Union and a treaty on good relations between the neighbouring countries was concluded in January 1992.

The need and opportunity for Finnish membership in the European Community (EC) increased greatly when Sweden submitted its membership application and the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991. Finland submitted its own application to the EC in March 1992 and the Parliament of the EC (by then the European Union), approved the application in May 1994. In a referendum held in Finland in October 1994, 57 percent of the voters supported membership, and in November 1994 Parliament approved Finnish EU membership as of the beginning of 1995 by a vote of 152-45.

In the 1995 parliamentary elections the Finnish Centre Party suffered a crushing defeat and Paavo Lipponen, the new chairman of the Social Democratic Party, formed a unique government by Finnish standards. Apart from its backbone, comprising the Social Democrats and the National Coalition, the government included Greens, the Left-Wing Alliance and the Swedish People’s Party.

Parliamentary elections in spring 2003 also changed the political composition of the government. The National Coalition Party was excluded from Centre Party leader Anneli Jäätteenmäki’s government, which comprised the Centre Party, the Social Democratic Party, and the Swedish People’s Party. Jäätteenmäki herself, under political pressure, soon had to resign and in June 2003 Matti Vanhanen became prime minister.

In 2006, an unexpectedly close presidential election took place. The incumbent, President Tarja Halonen, representing the left side of the political spectrum, defeated her opponent Sauli Niinistö, from the conservative National Coalition Party, by less than four percentage points.

In the elections of 2007, the Parliament shifted noticeably to the right when the National Coalition Party scored a big victory and the Social Democratic Party suffered a marked loss. Prime Minister Matti Vanhanen, from the Centre Party, continued in his post, gathering together a conservative–centrist coalition government, which began its term in April 2007. Of 20 ministers, eight represented the Centre Party and eight the National Coalition Party. The Green Party and the Swedish People’s Party were also granted ministerial posts.

Finland’s security policy has recently been the subject of energetic debate. Adding their own spice to the discourse were the enlargements of the European Union and NATO in 2004, events that placed Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, Finland’s neighbours to the south, among the new members of both organisations. In June 2008, Finland’s Parliament approved the changes to the constitution of the European Union in the Treaty of Lisbon.

Presidents of Finland |

|

| Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg (1865–1952) | 1919–1925 |

| Lauri Kristian Relander (1883–1942) | 1925–1931 |

| Pehr Evind Svinhufvud (1861–1944) | 1931–1937 |

| Kyösti Kallio (1873–1940) | 1937–1940 |

| Risto Ryti (1889–1956) | 1940–1944 |

| Gustaf Mannerheim (1867–1951) | 1944–1946 |

| Juho Kusti Paasikivi (1870–1956) | 1946–1956 |

| Urho Kekkonen (1900–1986) | 1956–1981 |

| Mauno Koivisto (1923–2017) | 1982–1994 |

| Martti Ahtisaari (1937–2023) | 1994–2000 |

| Tarja Halonen (1943-) | 2000-2012 |

| Sauli Niinistö (1948-) | 2012– |

By Dr Seppo Zetterberg, professor of history, University of Jyväskylä, updated May 2017