The World Press Freedom Index for 2016 gives Finland top ranking for the seventh year running.

Published annually by the Paris-based organisation Reporters without Borders, the World Press Freedom Index ranks 180 countries using criteria on the independence and pluralism of the media, the transparent flow of information, legal frameworks, and the safety and freedom of journalists.

The 2016 rankings show Finland in first place again. UNESCO’s choice to hold this year’s World Press Freedom Day event in Helsinki on May 2-4, also reflects the reputation of Finland’s free press.

“We’re proud to be so highly rated in this influential index, which is widely respected by international organisations,” says Ilkka Nousiainen, Chairperson of the Finnish branch of Reporters without Borders, which was set up in 2013 by Finnish journalists interested in press freedom at home and around the world.

Nousiainen believes Finland’s top rating is largely due to the high levels of freedom enjoyed by journalists in their everyday work. “Our journalists can write freely without interference from media owners or the government,” he says. “We also have very effective laws and institutions in place to help guarantee press freedom.”

One key organisation is Finland’s Council for Mass Media (CMM), which is jointly run by media publishers and the national journalists’ union to defend freedom of speech while also ensuring good journalistic practice and dealing with complaints through self-regulation.

CMM’s Chairperson Elina Grundström emphasises that long-standing Finnish legislation supports the freedom of the press by promoting transparency. “The Act on the Openness of Government Activities means all kinds of official documents are by default publicly available, except for very few documents justifiably designated as secret,” she says.

Ilkka Nousiainen agrees that Finnish journalists appreciate this openness – which even extends to the tax payment records of individual citizens – as well as the relative approachability of Finnish politicians and business figures. He feels the mainstream media are suitably objective, critical and diverse, even if the public broadcasting company YLE and the leading national daily newspaper Helsingin Sanomat sometimes seem to have a dominant role in shaping public opinion.

Enthusiastic readers with an eye for quality

Grundström also appreciates the plurality of the Finnish media: “I don’t think any other small country with a language spoken by so few people could have a media market of such high quality and diversity,” she says.

Figures compiled by Media Audit Finland show that 93% of Finnish adults regularly read printed or digital newspapers. The printed media market is highly diverse for a country of just 5.5 million inhabitants, with more than 200 national or regional newspapers published at least weekly, and more than 4,000 magazines produced for different interest groups.

“Recent surveys show how Finns are starting to look to traditional newspapers again for quality analysis and balance, in a healthy reaction to the turbulence and unreliability of the social media,” Nousiainen points out.

Finland ranks third in the world for newspaper readers per capita. The printed media market is highly diverse for a country of just 5.5 million inhabitants, with more than 200 national or regional newspapers published at least weekly. Most households subscribe to a daily paper and several magazines, while also receiving many free magazines and newspapers. Photo: Mikko Stig/Lehtikuva

Threats to freedom of speech

Like their counterparts in other countries, Finnish journalists have recently been increasingly targeted by online hate speech. Ilkka Nousiainen and Elina Grundström deplore this trend, and hope it won’t make Finnish journalists too cautious when writing on issues that provoke strong feelings, such as immigration, the refugee crisis, feminism, diets, hunting and gun laws. But they feel that self-censorship by the Finnish media on political issues has not been an issue since the days of the Cold War, when journalists used to be wary of criticising the Soviet Union.

According to Grundström, ongoing cuts by broadcasting and publishing companies represent a more serious threat to diversity and quality in Finnish media. “Finns tend to take the freedom of the press for granted, without realising it’s the product of journalists’ efforts over a long period. It’s worrying to see what’s happening to press freedom in parts of Eastern European and elsewhere,” she says.

The 2016 index shows an alarming rise in violations of media freedom worldwide due to religious intolerance, safety problems in conflict zones, and the increasingly authoritarian tendencies of many governments and media-owning oligarchs. The UNESCO event in Helsinki aims to promote freedom of information worldwide as a fundamental human right, to protect the press against censorship and excessive surveillance, and to ensure safety for journalists working both in the traditional media and online.

In Finland, a whole year of 2016 will be dedicated to the 250th Anniversary of the world”s first Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), the theme of the year being “Right to Know, Right to Say”.

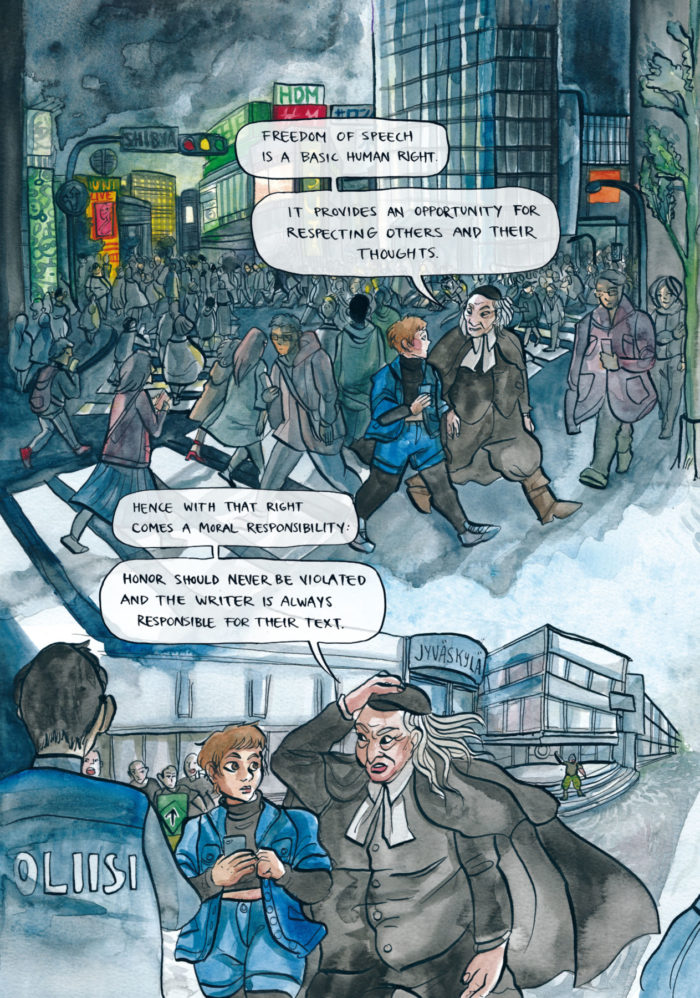

The Finn Anders Chydenius was one of the most notable politicians of eighteenth century Sweden-Finland. According to him, democracy, equality and a respect for human rights were the only way towards progress and happiness for the whole of society. His most important political accomplishment is the world´s first Freedom of the Press Act. Image: Siiri Viljakka, Script: Lauri Tuomi-Nikula/Last Words – the Return of Anders Chydenius.

Support for journalists working in countries with less freedom

To help budding investigative journalists and other media workers in countries where the freedom of the press cannot be taken for granted, the Finnish Foundation for Media and Development (Vikes) uses funding from the Finnish journalists’ union, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the EU to run projects where Finnish journalists’ expertise is used in training and networking. Many journalists from Somalia, Nigeria, Tanzania, Myanmar, Nepal, Nicaragua, Palestine, Eastern Europe and Central Asia have benefitted from such support.

By Fran Weaver, April 2016