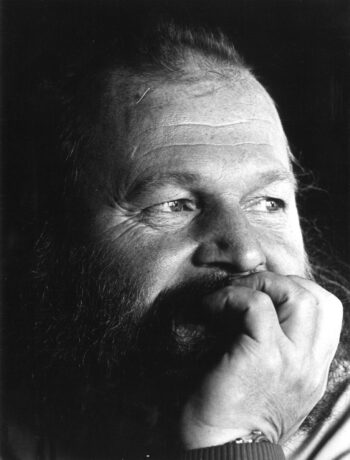

Reidar Särestöniemi (May 14, 1925–May 27, 1981), an eccentric artist from northern Finland, captured the untamed beauty of his home region in his bold, colourful paintings.

As a boy, he was a peculiar, lonely child with more friends among animals than people. He ran off into the forest to explore, and played mischievous tricks on the farm animals.

He wasn’t suited to working on a small family farm. He didn’t show any interest in learning how to do the chores.

He considered the fast-flowing Ounas River, which flowed past his home, to be his brother. That was his nature.

Northern origin

Born in the village of Kaukonen, he was the youngest of Matti and Alma Särestöniemi’s seven kids. As a child, he mixed buttermilk and flower petals to create paint, and sometimes used ash to mix paint if nothing else was available. He had to draw and paint – he just had to. Nothing else could hold his interest.

It wasn’t easy to rise from such modest origins to the top of Finland’s cultural scene. Yet he did it.

A striking impact

Reidar Särestöniemi (1925–1981) felt a profound connection with nature, which greatly influenced his art. Photo: Unto Järvinen/HS/Lehtikuva

Helsinki’s Didrichsen Art Museum received record-setting amounts of visitors in the spring of 2025, as tens of thousands of viewers arrived to see Särestöniemi’s colourful paintings on display in On the world’s shore: Reidar Särestöniemi 100 years (until June 1, 2025).

The large, vibrant artworks attract attention, and people queue to get a closer look. Orange tundra and a red sun stand out on the museum walls. Delicate, frost-covered birch branches are frozen in time. Reindeer graze, and cottongrass seems to sway gently in the wind.

Museum director Maria Didrichsen believes Särestöniemi’s art is being re-evaluated today. “His artworks are not meticulously representational, yet they are surprisingly easy to understand,” she says.

She thinks the steadily increasing flow of tourism to Finnish Lapland has brought Särestöniemi’s art closer to people. While his colours were once considered too vivid, those who have visited the far north of Finland realise that they are true to life.

“There is power in his art, and the large scale of his pieces creates a striking impact,” says Didrichsen. “Many viewers find themselves absorbed in his artworks, drawing comfort and energy from them, especially in these unsettled times.”

Obsessive dedication

In one night the north wind filled the fen full of flowers (1971): In northern Finland, spring arrives late, but with great intensity. Särestöniemi believed summer there was so short that the first spring blooms already carried autumn shades of red. Photo: Rauno Träskelin

The boy from far above the Arctic Circle eventually ended up in art school and became a professional artist.

After the Second World War, Särestöniemi’s mother found him his first private teacher, who in turn enabled him to attend the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki, at the age of 22. Around the same time, he started studying at the University of Helsinki’s Department of Drawing.

Moving from the middle of the wilderness to the bustling capital of Finland was a huge change for Särestöniemi. His home in Kaukonen was at the end of a dirt road, and now trams and cars were whizzing by.

At school, Särestöniemi painted with obsessive dedication, starting at nine in the morning and continuing until almost midnight. He was restless, completely different from the other students. He couldn’t sit still; he hopped from one easel to another like a bluethroat, a songbird that spends the summer in the far north.

But the young man learned, at an astonishing pace.

Lasting impressions

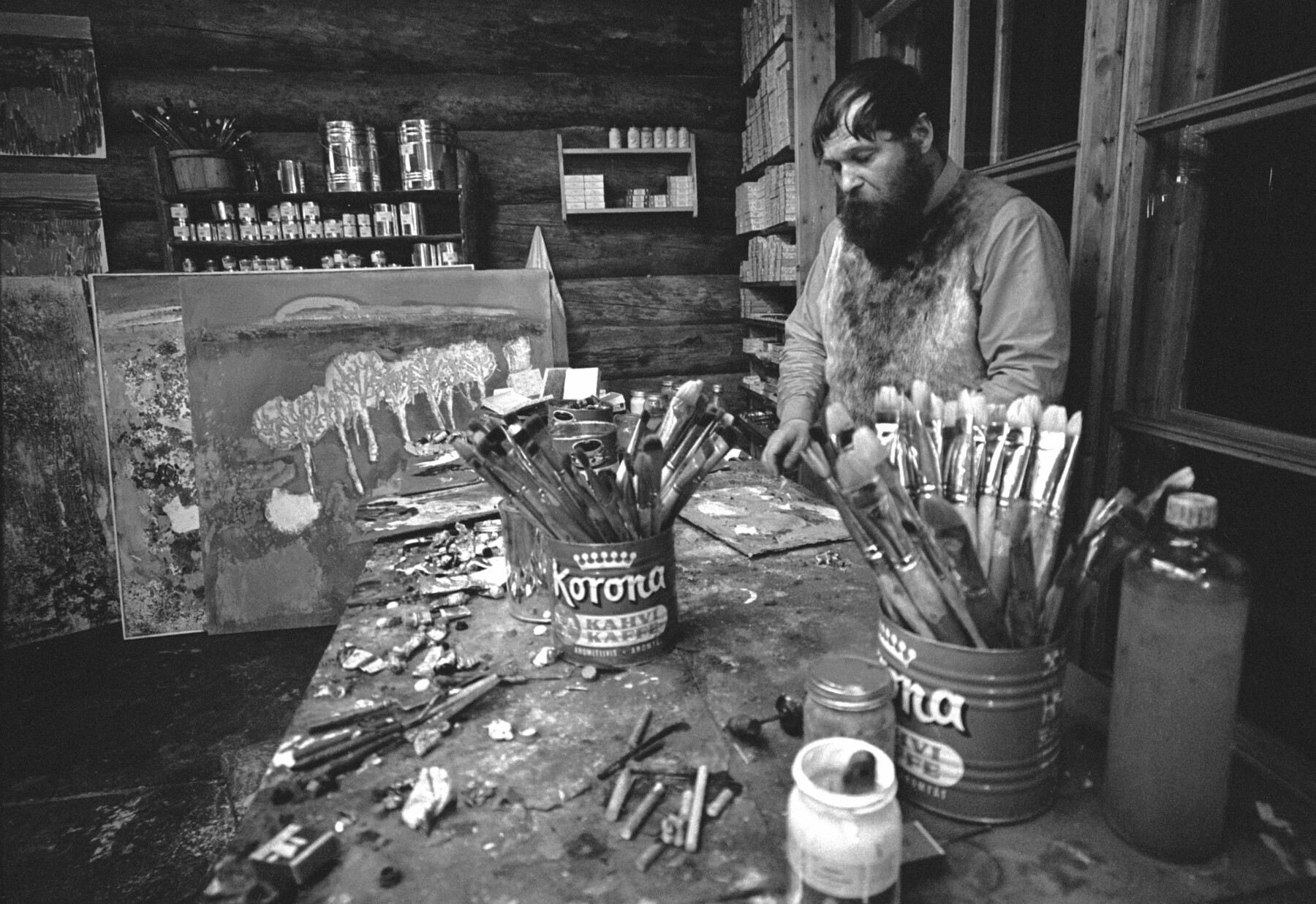

Särestöniemi chose to live and work on his family’s old homestead.Photo: Kaius Hedenström/Lehtikuva

In 1952, Särestöniemi travelled to Paris for the first time, for inspiration. The experience left a lasting impression on his output.

He visited the Louvre almost every day for a month, then discovered the works of Mexican artist Diego Rivera, and fell in love with the work of Russian-French artist Marc Chagall. Särestöniemi wondered how anyone could paint such fairytale-like pieces; it was as if images were being used to recite poems.

In Paris, Särestöniemi felt like he could truly be himself. He didn’t need to hide anything — he was free. The French capital was a metropolis with countless opportunities, whereas Finland seemed distant and removed.

When Särestöniemi returned from the Continent to his home in Kaukonen, it was time for a long, laborious winter. He had raised the money for his trip by promising to sell timber from his family’s land, and now he had to fell 300 trees in the forest.

Fragile northern nature

Meeting of the Fugitives (1969): The love of Särestöniemi’s life was the poet Yrjö Kaijärvi. Särestöniemi often included subtle hints about his sexuality in his paintings or their titles.Photo: Rauno Träskelin

Nature conservation later became an important theme in Särestöniemi’s art. He was ahead of his time in criticising the use of plastic, and the protection of animals, forests, and rivers was a passion for him.

He couldn’t accept the threat of a dam on the Ounas River. He didn’t want to see the fragile northern nature disappear.

Särestöniemi portrayed himself as various animals in his paintings: When he wanted to depict himself as playful and powerful, he painted a lynx. The willow grouse represented his fragility.

When he painted a wolf, Särestöniemi wanted to emphasise its rarity. Perhaps he perceived himself as cornered like a lonely wolf at times. He was gay in an era when homosexuality was punishable by law in Finland.

He hid subtle messages in his paintings, such as bears with beards embracing one another. The allusions were visible to all but understood by few. He was hidden, and therefore he was safe.

Drawing attention

Marie-Louise and Gunnar Didrichsen, founders of the Didrichsen Art Museum in Helsinki, first met Särestöniemi in 1968, and later acquired several of his works.Photo: Rauno Träskelin

Särestöniemi dared to defend individuality. He was a unique man himself, too.

At a time when bearded men were viewed with suspicion in his home village, he grew a long black beard and proceeded to dye it bright red.

He walked down the village road in Kaukonen dressed in Spanish-style clothes together with leather boots made by the Sámi, the Indigenous People of northern Europe. The locals would comment that he wore summer clothes in winter and winter clothes in summer.

It was as if he enjoyed drawing attention to himself, being part of a big performance. He was large and colourful, just like his paintings.

He didn’t hold back

The Didrichsen Art Museum’s exhibition celebrating the centenary of Särestöniemi’s birth attracted record amounts of visitors.Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

Särestöniemi found his own unique, slightly naïve style when he returned from a study trip to Leningrad in the Soviet Union, in 1959. He had learned to find the colours of nature on his palette, and used bold, confident strokes.

He didn’t hold back on colours. He could pour an entire can of paint onto a piece, spreading, smearing and working it into a painting.

He always knew that his art would be recognised, that he would become famous. Popularity arrived quickly. People loved the exotic, eccentric artist, whose large-scale works seemed to blaze with intense colours.

And the artworks sold well, fetching record prices. When Särestöniemi went to deposit the money from his paintings at his tiny local bank office, a thankful and astonished bank manager shook his hand warmly.

Self-expression

Heart of winter (1980): Särestöniemi despised the polar night of winter for most of his life, but in his later years he decided to make peace with it. He painted this bright birch grove amidst the snow.Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

Some people thought Särestöniemi was arrogant. He was special, no one could deny that.

But perhaps his arrogance was really sensitivity? A way to express himself, to seek a path to freedom?

The Finnish media often portrayed him as a mystical figure who hosted royalty and other celebrities at his wilderness studio. However, Särestöniemi longed for the approval of the art-world elite, which he never truly received during his lifetime.

He travelled a lot, visiting Antarctica and the Norwegian Arctic outpost of Svalbard and everywhere in between. Särestöniemi sometimes journeyed as far as he could away from the long, cold winters of northern Finland, but he always returned.

The nature, fells and tundra of the far north meant everything to Särestöniemi. He felt a true connection with them, and expressed it in paint with great passion.

Särestöniemi died in northern Finland at the age of 56 in 1981. The Ounas River continued to flow freely.

By Emilia Kangasluoma, May 2025

This article is partially based on information from Noora Vaarala’s book Sarviini puhkeaa lehti (Gummerus, 2025).

The Särestöniemi Museum in Kaukonen includes Reidar Särestöniemi’s home and studio and a gallery.