On the occasion of her 150th birthday, Finnish museums honour Helene Schjerfbeck, a bold artist who was ahead of her time – and whose paintings are now worth millions of euros.

More than six decades after her death, the work of Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946) is more vital than ever. Her career mirrored – and presaged – the arrival of modernism. It began with realist village scenes from France and Cornwall in the 1880s and climaxed with haunting, cartoonish self-portraits during the Second World War.

Schjerfbeck’s international stock has been rising since a milestone New York show two decades ago. Her works have fetched auction prices previously unseen for Finnish artists, such as nearly four million euros for her Dancing Shoes at Sotheby’s in London.

In 2012, several Finnish museums are saluting her 150th anniversary with exhibitions. The biggest takes place at Helsinki’s Ateneum, while museums in Tammisaari on the south coast and Vaasa on the west coast are also in on the action.

Rediscovering her originality

At Ateneum, the largest-ever Schjerfbeck retrospective features nearly one third of the roughly 1,000 paintings she created during her lifetime. The show also includes work by artists who inspired her. Schjerfbeck paintings influenced by 16th-century Spanish master El Greco will for the first time be shown beside his originals.

“Of course, Schjerfbeck was influenced by other artists, but their influence is difficult to pinpoint as she filtered her impressions of others’ work and drew her own artistic conclusions,” notes curator Vesa Kiljo of the Provincial Museum of Western Uusimaa, known by its abbreviation, EKTA. It houses a more modest, intimate permanent exhibition on Schjerfbeck in the south-coast town of Tammisaari, where the artist lived between 1918 and 1941.

Helene Schjerfbeck: Dancing shoes (1939 or 1940), Private collection. Photo: Finnish National Gallery, Central Art Archives/Kari Lehtinen

Helene Schjerfbeck: Red Apples (1915)Photo: Finnish National Gallery, Central Art Archives/H. Aaltonen

Helene Schjerfbeck: The Convalescent (1888)Photo: Finnish National Gallery, Central Art Archives/Hannu Aaltonen

“Recognition of her originality is the basis on which respect for her as an artist has constantly increased over the years both at home and abroad,” says Kiljo.

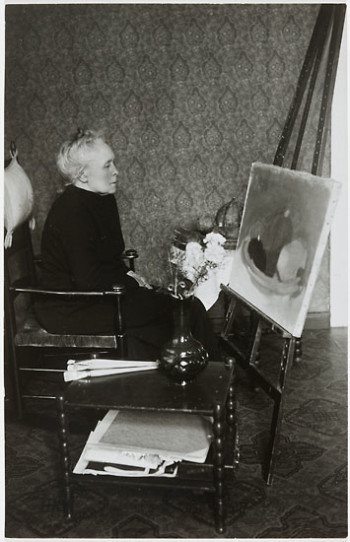

Her studio has been partially recreated at the museum. On display are her easel and a rocking chair that features in many of her pictures. Films, photos and letters help to explore Schjerfbeck’s world. Local actor and guide Anne Ingman impersonates Schjerfbeck, and is on hand on July 10, 2012 as the museum celebrates the painter’s birthday with cake and free admission.

Frida Kahlo, Edvard Munch and Schjerfbeck

That kind of hoopla would no doubt have horrified Schjerfbeck, described by her neighbours as shy and introverted. The Independent has written of her: “Imagine the life of Frida Kahlo yoked to the eye of Edvard Munch, and you’ll begin to get the measure of this oeuvre.”

Helene Schjerfbeck paints at her home in Tammisaari in 1937.Photo: H. Holmström FNG/CAA/Coll. Gösta Stenman

While Schjerfbeck’s life was not as dramatic as Kahlo’s, she too had a tough one. After breaking a hip in a childhood accident, Schjerfbeck became a recluse who walked with a limp and battled illnesses most of her life. She never married, despite one engagement and a long-term unrequited friendship, and spent many years caring for her ill mother – who was Scherfbeck’s other primary model besides herself.

Schjerfbeck is best known for her self-portraits, shown at EKTA as a row of reproductions of 36 works from 1878 to 1945. “Now that I so seldom have the strength to paint, I’ve started on a self-portrait,” she wrote to a friend in 1921. “This way the model is always available, although it isn’t at all pleasant to see oneself.”

While her early self-portraits were naturalistic, the last ones are just a few stylised strokes. Some other portraits – such as The Californian and The Gipsy – show eyes downcast or turned away, which can paradoxically reveal a great deal about a subject.

“She wanted to capture the inner person, not just the exterior,” says Kiljo.

By Wif Stenger, June 2012