On a weekday afternoon in New York City, several American women are touring Independent Visions: Helene Schjerfbeck and Her Contemporaries, an exhibition of 55 artworks by four Finnish painters at Scandinavia House on Park Avenue. “Very nice,” says one of the patrons, “but a little depressing.”

The pieces come from the collection of Helsinki’s Ateneum Art Museum (many of them return to Ateneum in Urban Encounters, showing until January 20, 2019), and some of them do reflect a kind of melancholia that attended the cultural and political transformations as Finland moved, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, toward creating a national identity and achieving independence.

Art made during the shift away from the Russian Empire and from Swedish influences unavoidably mirrors a tumultuous era during the development of a progressive nation that celebrated its centennial in 2017. The early 1900s included the Civil War in 1918, less than a year after independence, and the Second World War, which the Finns divide into the Winter War of 1939–40, the Continuation War of 1941–43 and the Lapland War of 1944–45.

Issues of humanity

In Ellen Thesleff’s “Decorative Landscape” (1910), a female figure is visible in the lower right area of the painting, dwarfed by the trees.Photo: Yehia Eweis/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum

The creative growth of the celebrated Schjerfbeck (1862–1946) and the exhibition’s other three artists coincided with the notions of equality, cultural development and educational opportunities necessary for the establishment of a sovereign state. Schjerfbeck, Ellen Thesleff (1869–1954), Sigrid Schauman (1877–1979) and Elga Sesemann (1922–2007) weren’t isolated from the political upheaval of the times, either.

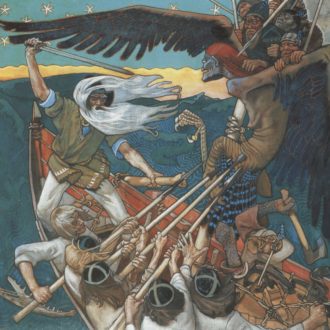

The era’s male artistic giants – notably composer Jean Sibelius, artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela and author Juhani Aho – are often considered to have formed the vanguard of Finland’s cultural and political identity and the drive to create a distinctive Finnish character. However, female colleagues such as the pioneering Schjerfbeck, one of the country’s best-known painters, had a significant role, though it was overlooked at times.

“Although there were a limited number of academic people at the time, artistic talents rose up,” Risto Ruohonen, general director of Finnish National Gallery, tells me. “A relatively small part of the community had a strong ideological philosophy where politics and art were so closely combined.” These individuals had an influence on both spheres.

Climate of equality

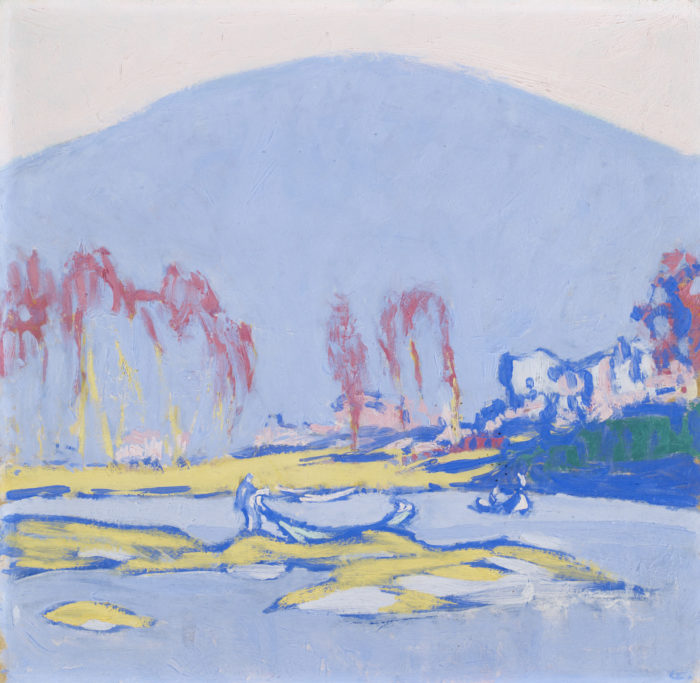

Sigrid Schauman created “Italian Landscape” in the 1930s. All four of the artists in the exhibition lived or worked on the Continent at some point.Photo: Pirje Mykkänen/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum

Schjerfbeck, Schauman and Thesleff came of age as artists during a critical time in the development of an autonomous Finland. Until 1846, there were no Finnish art schools, unified art collections or news coverage of the cultural scene. That was the year the Finnish Art Society was founded (it later gave rise to Ateneum). Soon afterward, grants were established for studying the arts at home and abroad (mostly in France and Italy; all four of the artists worked or lived on the Continent at various points in their careers). The support was made available to all who qualified, in a climate of equality.

Female Finnish artists began to use their voices during the late 19th century, an unprecedented time in the burgeoning nation’s pursuit of social and educational egalitarianism. It was also a matter of necessity, as the four artists largely supported themselves throughout their lives, notes Susanna Pettersson, director of Ateneum. Schauman, who was also a teacher and a newspaper art critic, accomplished a number of her works after her 70th birthday.

Growing pains, brooding portraits

This Elga Sesemann self-portrait from 1946 depicts the artist without eyes. That may be a sign of the grim realities of the time.Photo: Yehia Eweis/Finnish National Gallery

The show features Schjerfbeck’s intricate self-portraits, Thesleff’s imaginative woodcuts, Schauman’s lavish landscapes and Sesemann’s introspective expressionist portraits. Part of Finland’s celebration of 100 years of independence, the exhibition started in New York in the autumn of 2017, then reappeared at Millesgården in Stockholm under a new name, The Modern Woman, during the winter of 2017–18. From October 19, 2018 to January 20, 2019, many of the same paintings are on display at Ateneum in Helsinki as part of a larger exhibition entitled Urban Encounters.

Some of the works reflected the growing pains involved in the creation of a new independent country, and were occasionally brooding portraits of a nation at war. Thesleff’s Finland’s Spring, completed in 1942, portends the optimism of shaking off winter, but also some of the grim realities during conflict with Russia. Sesemann’s Self-Portrait (1946) depicts the artist without eyes. Throughout the exhibition, a sense of Finnish period realism seldom available to American audiences shines through.

Some struggles via the lens of artists, though, are universal and timeless. “One wants to portray that which is innermost, passion,” Schauman wrote during her career, expressing a goal shared by many of her colleagues.

She continued the thought like this: “And then you become ashamed and cannot because you are a woman.” Some artistic challenges, we hope, are consigned to the past.

Excerpts from the exhibition

Full version of Helene Schjerfbeck’s “Self-Portrait, Black Background” (1919) Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum/Hallonblad Collection

Helene Schjerfbeck: Girl from Eydtkuhnen II (1927) Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum/Kaunisto Collection

Helene Schjerfbeck: Girl from California I (1919) Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum/Kaunisto Collection

Helene Schjerfbeck: Red Apples (1915) Photo: Henri Tuomi/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum/Kaunisto Collection

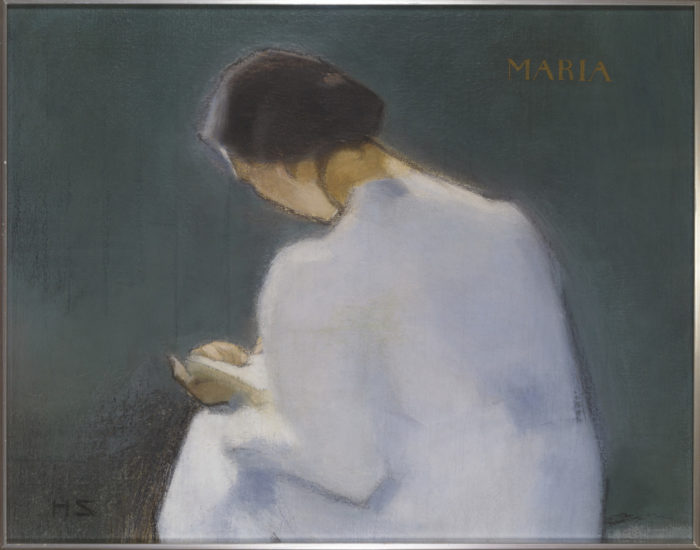

Helene Schjerfbeck: Maria (1909) Photo: Yehia Eweis/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum

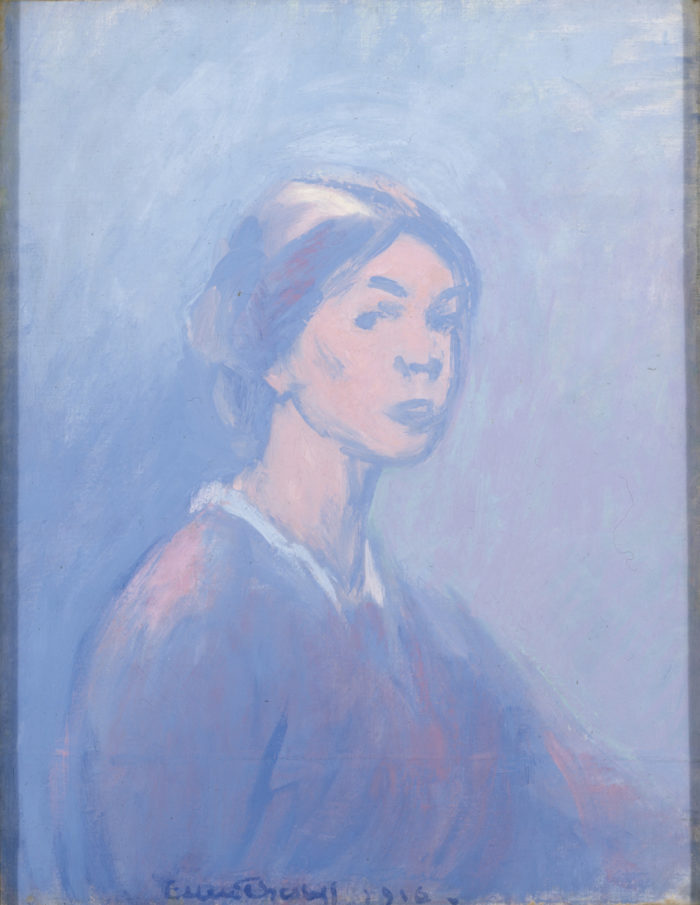

Ellen Thesleff: Self-Portrait (1916) Photo: Pirje Mykkänen/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum/Hallonblad Collection

Ellen Thesleff: Marionettes (1907) Photo: Jouko Könönen/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum

Ellen Thesleff: Italian Landscape (undated) Photo: Kirsi Halkola/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum/Kaunisto Collection

Elga Sesemann: Street (1945) Photo: Hannu Karjalainen/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum

Sigrid Schauman: Model (approximately 1958) Photo: Janne Mäkinen/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum

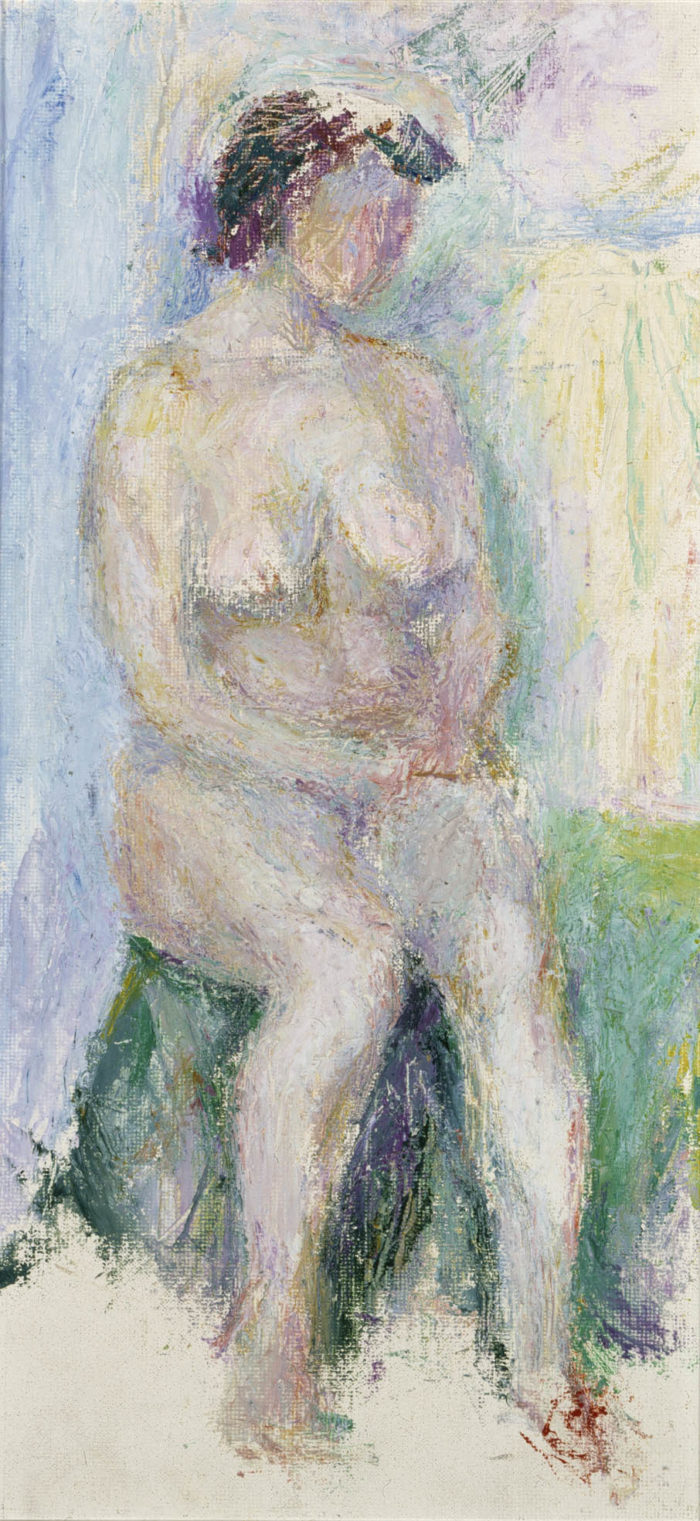

Sigrid Schauman: Nude (1954) Photo: Pirje Mykkänen/Finnish National Gallery/Ateneum Art Museum/Antell Collection

By Michael Hunt, June 2017, updated October 2018