Finland’s national identity is deeply associated with the Kalevala, a work of epic poetry compiled in the 19th century from an oral tradition of ancient folklore and mythology.

February 28 is officially designated as both Kalevala Day and Finnish Culture Day.

Numerous artists, writers and musicians have sought inspiration from the Kalevala, most notably during the national romanticism of the late 1800s. However, few have captured the Kalevala spirit quite like Finnish painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865–1931). His illustrations of the epic stirred the imaginations and passions of readers who, through his brush, could see the olden texts come to life.

Some of Gallen-Kallela’s most famous Kalevala-inspired masterpieces, such the Aino Myth triptych, are displayed at Ateneum Art Museum, the classical branch of the Finnish National Gallery in Helsinki. They stand as a testament to a vision of Finland that originated in the past.

But what does it mean to be a Finn in modern times, and how does that connect with the Kalevala?

Connecting past and present

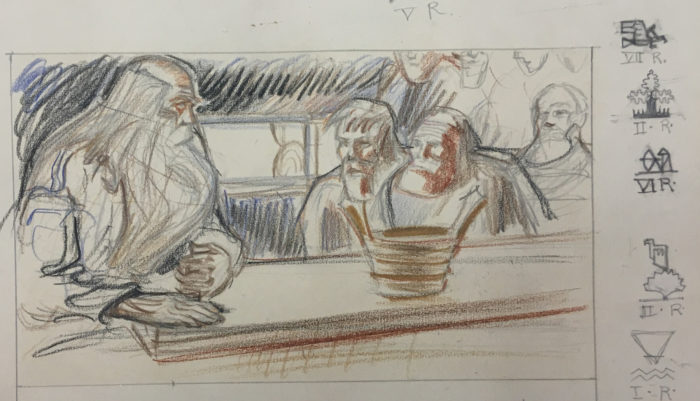

Gallen-Kallela drew this sketch in preparation for the Great Kalevala, a richly illustrated version that remained unfinished at the time of his death.

Photo: Mari Viita-aho/Gallen-Kallela Museum

An exhibition at the Gallen-Kallela Museum, just west of the capital in the neighbouring municipality of Espoo, tries to answer those questions with some of the painter’s lesser known, yet highly relevant, Kalevala-related works (until May 5, 2019). Entitled The Kalevala, In Other Words, the show features preliminary sketches of his classics that give insight into the development of Gallen-Kallela’s Kalevala oeuvre, as well as never-before-seen and unfinished works by an artist who helped form the nation’s character.

“One of our goals in this exhibition is to make more connections with Kalevala to the present day and contemporary times,” says Mari Viita-aho, the museum’s project planner. “We want to ask, ‘What does it mean to be Finnish today?’”

Part of the appeal of any exhibition at the Gallen-Kallela Museum is the building itself. Located in the rustic, seaside Tarvaspää area, it was completed in 1913 as a grand, turreted home for Gallen-Kallela and his family. It has operated as a museum since 1961, and part of In Other Words is housed in the painter’s spacious studio, which still looks much as it did when Gallen-Kallela created his famous works. Exhibits are also placed in what were once the family’s kitchen, dining room and living room.

Climbing to culture and history

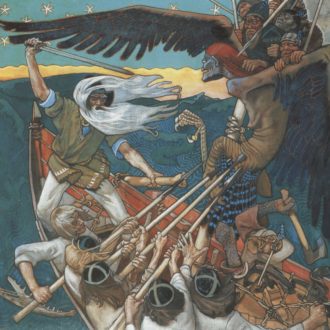

This drawing, The Defence of the Sampo, shows a key scene from the Kalevala; the sampo is a mystical source of power or wealth. Gallen-Kallela also made a very different painting of the same name, which he reproduced as a mural on the ceiling of the National Museum in Helsinki.Photo: Jukka Paavola/Gallen-Kallela Museum

Supporting the contemporary theme of In Other Words, the rooms in the tower feature the culture, history and everyday life of Espoo. Visitors can climb the steps to the top room, with its sweeping views over an inlet of the Baltic Sea. Idyll, an installation by the Espoo Artists’ Guild, centres on a large egg, a significant creation-myth symbol from the Kalevala, suspended in mid-air over a nest-like construction. The work incorporates video and audio collected in Espoo.

In another room, audio recordings of local storytellers play in nine of the many languages spoken in Espoo. The stories in Finnish, Swedish, Russian, Estonian, Arabic, English, Vietnamese, Hindi and Lithuanian lend a modern, relevant subtext to the ancient Kalevala. Sixteen percent of Espoo’s 214,000 residents have a native language that is not Finnish or Swedish, which are Finland’s official languages.

“When we made this exhibition we asked the question, ‘What is Kalevala all about?’” says Viita-aho. “We came to the conclusion it was about people meeting people and telling stories and spreading the information of cultural heritage onwards. That stands as the essence of Kalevala for current times.”

Revealing personal touches

Lemminkäinen’s Mother, on show at the Gallen-Kallela Museum, depicts a Kalevala scene. This version is only about three centimetres wide; a much larger, more detailed painting is located in Ateneum Art Museum.Photo: Jukka Paavola/Gallen-Kallela Museum

The exhibition centrepiece, located in Gallen-Kallela’s studio, tells the story of the women of the Kalevala. There, personal touches are revealed: The model for Gallen-Kallela’s painting of Aino, a heroine from the epic, was his wife, Mary.

For Lemminkäinen’s Mother, a Gallen-Kallela masterpiece that hangs in Ateneum, the model was the artist’s own mother. And he painted the visage of Louhi, the mythological wicked queen, as a composite of faces he encountered during his visits to the Finnish countryside.

“He had a lifelong relationship with the Kalevala from a young age and was impressed from his first readings,” Viita-aho says. “He is not the only one who painted the Kalevala, but his paintings are the first that come to mind when people talk about the Kalevala.”

By Michael Hunt, February 2019