On March 15 and 16, 1907, European history was made in the towns and rural hamlets of Finland. In the national election held on those two days, every citizen aged 24 and over, the humblest maid and crofter included, was allowed to vote.

In those days people made their way to the nearest village – in many cases on skis across the hardened snow of early spring – to put a red line in the box of their choice on a ballot paper.

Finland had been a Grand Duchy of the Russian empire since 1809. During that period there was a legislative assembly, a Diet, in Finland but it had very limited powers and comprised only male representatives of the upper levels of society, and it convened infrequently.

After Russia’s defeat in the war against Japan, internal political opposition against the imperial tsarist regime increased. This unrest spread to Finland, where a general strike began at the end of October 1905. As a result of the unrest, the tsar issued a manifesto which decreed that a Parliament based on universal suffrage would be established in Finland with powers to ensure the legality of the measures taken by the country’s Government.

Preparations for parliamentary reform started right away and the principle that the right to vote and to stand for election would be granted to both men and women was approved right from the start of the process. The Diet convened to approve the reforms on June 1, 1906, and elections were ordered to be held in the spring of the following year.

“Finnish women supporting precious matters of conscience”

Several months were needed for the preparations as the parliamentary reform signified a major upheaval in the whole political arena. The parties of the time were mainly debating societies and discussion groups but they began to reorganize in readiness to exert political power, and several new parties were established.

It took just under a year to organize polling stations, election committees, vote counting procedures, nomination of candidates, and to provide citizens with information on how to exercise their right to vote. Women in particular needed to be enlightened and awakened to the new opportunity.

Sisters,

The time for the elections is drawing near.

The Finnish woman is the first in Europe to whom suffrage has been granted. Let us perform with honour the duty that this entails. Sisters! Let us ensure that not one of us is absent when the composition of Finland’s first truly democratic Parliament is being determined. A heavy burden of responsibility will lie on the shoulders of the woman who stays away from the election without due cause.

Matters of conscience that Finnish women hold dear are first and foremost:

- Supporting the State Church

- Furthering decency

- Establishing prohibition

- Improving the position of women.

All those issues will be debated in Parliament. Therefore, sisters, rise up to cleanse society and vanquish the enemies of our homes.

– From Mrs Hedwig Gebhard’s election proclamation –

The first elections were successful. The turnout was 70.7 per cent and no irregularities or public disorder took place. Most Finns were at least moderately literate, and the national awakening that had been taking hold in the country for several years was linked to the creation of ideological and political organizations.

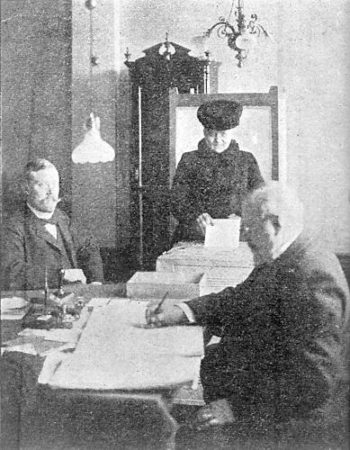

Elections 1907: a polling station in Helsinki.Photo:

Finnish Heritage Agency

The election results became clear within a few weeks. The Social Democratic party was the largest, winning 80 of the two hundred seats. The moderate, conservative Old Finns party won 59 seats, but the parties in power at the time fared badly. The progressive, bourgeois Young Finns won 26 seats and the Swedish Party 24. The Agrarian Party, predecessor of today’s Finnish Centre Party, took 9 seats and the Christian Workers’ Union was left with 2.

Of the total of 62 women candidates, 19 (9.5%) were elected to the first Parliament, most of them representing the Social Democratic Party. The success of women in the first parliamentary elections can be regarded as good, since the number of women elected was lower on several occasions during the years before the Second World War.

First Parliament introduced prohibition

The new deputies were summoned to in Helsinki for the first time at the end of May 1907. The opening session of Parliament was held on May 25, 1907 in the assembly hall of a building, since demolished, belonging to the fire brigade in Hakasalmenkatu, a street now named Keskuskatu.

Much was expected of the new parliament; the air was thick with a sense of national identity and the euphoria of nascent self-determination. The work of the reshaped Parliament was begun by a man, the likes of whom had never been seen before in the corridors of power.

He, the oldest Member of Parliament, Mr I. Hoikka, a tenant farmer from Lapland, started his speech with the words “As a simple peasant from the furthest reaches of Lapland…” and went on to appeal to MPs to seek consensus despite differences and incompatibility among the parties and the recent passionate election campaign.

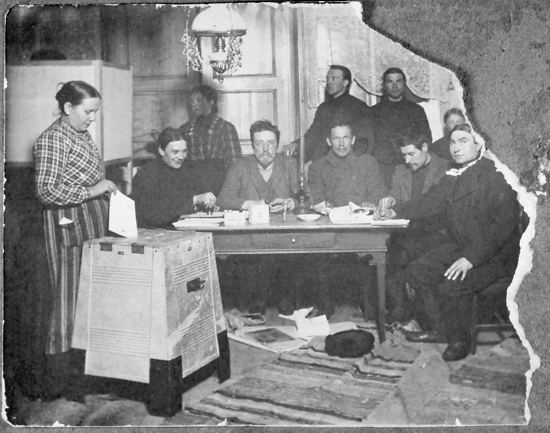

Elections 1907: a rural polling station in Ylihärmä, W Finland.Photo: Finnish Heritage Agency

The first session of Parliament lasted three months. Its significant achievements included an act on working hours for bakeries and a law prohibiting alcoholic beverages, issues backed by the workers’ movement and women’s groups. The prohibition law, however, did not actually come into force till more than ten years later.

Many proposals failed to progress through Parliament, such as legislation on land tenancy, business practices, disability and old-age insurance, and compulsory education. Legislative reforms in many key areas were only passed after Finland became independent in 1917.

The Tsar, who had the power to approve laws, considered Finland’s rising political activism a threat and left some laws unratified. The Conservatives, who advocated a policy of Russification in the autonomous regions, gained power in Russia.

In 1908, the Tsar issued a decree that made the procedure for dealing with matters concerning Finland less favourable for Finland. This triggered a storm of protest, as a result of which the Tsar dissolved Parliament and ordered new elections.

The first Parliament managed to sit for barely a year of its three-year term. This was repeated several times during the period of autonomy and new parliamentary elections were held nearly every year until independence.

By Salla Korpela, April 2006, updated 2011