Bertolt Brecht once noted that Finns are silent in two languages. Maybe so, but they write in three – Finnish, Swedish and Sámi – and the total number of titles published annually in Finland is tremendous. The country sees the publication of 13,000-14,000 books a year, over 4,500 of them new works. Only in Iceland are more books published per capita.

Finnish literature goes further than ever

Finns are also diligent readers, and the country’s extensive network of free libraries is largely to be thanked for this. Free admission to the world of knowledge is the key equalizing principle in cultural policy, and the figures are convincing: an average of over 19 library loans per resident per year. The library institution is vital for authors as well, as the compensation they receive from loans is an essential source of income for many.

In Finland, reading is a hobby that begins in the home at a young age: according to a study by Statistics Finland, about 70% of parents read out loud to their children. The latest PISA studies award Finnish pupils good results in reading skills, and in addition to the Disney characters known worldwide, favourite literary figures for Finnish children include Tove Jansson’s Moomintroll, who has appeared in just about every corner of the globe, and Ricky Rapper, whose adventures have been made into incredibly popular family films. One more revealing statistic: every third Finn reads literature every month, and this figure has remained stable since 2000.

E-books form a growing market in Finland. Getting in on the action are publishers, bookstores and even telecoms operators such as Elisa, whose store is shown here.© Elisa

Although the battle for readers’ free time has escalated – reading, after all, is a time-intensive activity – sales of literature have not notably declined since the turn of the millennium, and according to a 2008 ‘Finland Reads’ study, 16% of Finns buy over ten books a year. The 2010 statistics reveal a distinct, over 10% drop in total sales of literature – the first ever. Nevertheless, the book has maintained its position as a prestigious gift, despite the fact that, as elsewhere, paperback markets have expanded and new works are sometimes available in paperback during their year of release.

On the other hand, reading groups, social media, and popular blogs on literature have extended the group that critically assesses and recommends books. Although reading is a private experience, there is a desire to share it. In this sense, literature is a broad adhesive surface that binds people together.

With its e-books and print-on-demand, the current publishing environment has transformed the traditional role of the general-interest publisher. In recent years, Finland has seen the establishment of professionally run small presses that focus primarily on Finnish literature and nonfiction, with some degree of translations. Along with this development and in accordance with international trends, Finland has also seen the founding of its first literary agencies, which sell Finnish authors’ translation rights abroad, an activity that has traditionally been the sphere of publishing houses.

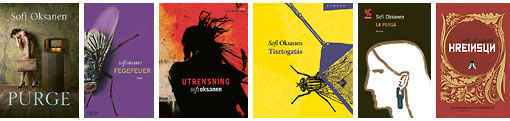

Translations of Sofi Oksanen’s prize-winning book Purge appear or are forthcoming in nearly 40 different countries. From left: UK, Germany, Sweden, Hungary, Italy and Iceland.

Furthermore, there has been growth in the sale of these translation rights: currently, approximately 200 Finnish titles appear in translation each year in almost 40 languages. The greatest number of these titles are published in Germany, with Sweden and Estonia following, but there are also, for instance, significant numbers of translations into Japanese. Finland has a broader tip of good literature these days, translator training has been bolstered, and sales efforts have been intensified. A good illustration of this is that FILI, the organisation dedicated to exporting and promoting Finnish literature, is now preparing for Finland’s theme year at the Frankfurt book fair in 2014.

This FINFO focuses above all on what type of literature is being written at the end of the first decade of the 2000s, and by whom. The new generation of writers, born in the 1970s and ‘80s and raised in an international environment, is gradually solidifying its position. Many of them write flexibly across genre boundaries: poems and prose, for children and adults. Literature by immigrant writers has also started to appear. Despite its uncertainty, the profession of author has traditionally been a respected one, and the system of grants – ranging from six months to five years in duration – is very good.

The polyphonic voice of contemporary Finnish literature is carrying further than ever.

Nina Paavolainen

On Finnish prose

Left: Aleksis Kivi’s Seven Brothers (1870) is regarded as the first significant novel written in Finnish.

Right: The Finnish national epic Kalevala forms the basis for popular children’s book The Canine Kalevala by Mauri Kunnas.

At the end of the first decade of the 21st century, Finnish literature bears international comparison well in terms of multidimensionality, despite the fact that Finland does not boast a particularly long literary history. National author Aleksis Kivi was the first master of Finnish-language prose, and his output coincided with the postromantic decades following the 1850s, while the Finnish national epic The Kalevala, compiled by Elias Lönnrot, appeared in 1835.

It should be noted that The Kalevala still holds influence today: even if you’ve never read it, its body of stories and imagery continue to have a powerful effect on the collective Finnish imagination. Comic book artist Mauri Kunnas’ The Canine Kalevala (new edition 2006) and a simplified version of The Kalevala intended for children (2002, English version 2009) remain incredibly popular. The Kalevala has been translated into over 60 languages, and Aleksis Kivi’s best-known work, Seven Brothers, which crystallises the tension between rural and urban, primitiveness and civilisation that has long shaped the core of Finnish identity, continues to be a favourite and benchmark for authors.

In Finland as elsewhere, the biggest sales figures are achieved by detective novels (Matti Yrjänä Joensuu, Leena Lehtolainen), thrillers (Ilkka Remes), family sagas (Laila Hietamies) and why not chick-lit-influenced portrayals of urban women (Katja Kallio). Also enjoying newfound status as a top-selling genre is the domestic comic book (embodied in such characters as Viivi and Wagner).

In addition, other quality prose is written in Finland, which in terms of style and subject more and more frequently finds its way across the nation’s borders.

The Historical Novel

Finnish literature has always included a powerful historical awareness. In the years of post-war growth and creation of national unity, literature had ideological tasks to fulfil, and up until the 1970s, it contributed to discussions surrounding the construction of the welfare state. Prior to this, Mika Waltari – in whose production novels situated in the past are read as depictions of the societal climate at the time of publication – created the 1945 work The Egyptian, which was translated into dozens of languages. Its status as a classic is by and large founded on its fundamental humanism, and Waltari remains among Finland’s best-known authors abroad.

Sofi Oksanen’s Purge (2008), one of Finland’s biggest international breakthroughs in recent years, revitalises the historical novel. Its Estonian-Finnish framework, fixed against a backdrop of recent European history, has spoken to readers as far away as the US, and in Finland alone the book has sold over 160,000 copies.

The popularity of Purge can be explained through a variety of factors. It takes a bold approach to the recent history of Finland’s sister nation, and its interpretations of the events of the Second World War, the relationship between the conqueror and the conquered, have generated much debate. The heroes end up turning into the losers, and during wartime everyone loses something, not least of all themselves.

Oksanen’s narration is not anchored in the tradition of realism; it is carried along by a profuse flow of lush and lingering verbs. The strong female perspective opens up a view to a mental landscape whose experiences have not received equal exposure. It gives a voice to a muzzled distress that no one has wanted to hear, and this is likely one reason why the work has tapped into such a broad base of identification. The story of three generations of women fleshes out the themes of nationalism and femaleness: women’s bodies and women’s work are both concretely and metaphorically instruments of warfare in which subjugation, humiliation, and shame are ever-present.

Sofi OksanenPhoto: Toni Härkönen

Furthermore, Sofi Oksanen represents the younger generation of writers in that she is happy to meet her readers, travels abroad continuously to speak about her work and raises topics of current interest when she makes an appearance. The media continues to write more about writers as phenomena rather than literature itself, but shifts in the publishing field and seemingly dramatic changes of publisher feed this orientation as well.

Examples also exist from recent years of the historical novel’s fragmentation to deal more problematically with the construction of Finnish identity over the last century. A fine illustration of its expansion into the mental-historical arena is Jari Järvelä’s trilogy, whose final segment has been appropriately named Kansallismaisema (‘The National Landscape,’ 2006). As old as his century, in other words 38 years old in 1938, the protagonist takes centre stage as the author carefully describes the painful birth of a common culture.

Jari Tervo, who has long belonged to the first tier of Finnish authors, frequently and very amusingly portrays ‘the common folk,’ particularly the people of northern Finland. His works that appeared in the years leading up to the 2010s, a trilogy that deals with Finnish history, do not form a chronologically linear whole: we begin from the Cold War era and end in 1920, in the period following the Finnish Civil War. Instead, it re-draws key turning points from the nation’s recent past, which in Tervo’s interpretation are linked by the fight against communism.

Leena Parkkinen’s strong debut Sinun jälkeesi, Max (‘After You, Max,’ 2009) resurrects the past milieu of 1920s Helsinki, but its broader framework is the European worldview and its questions universal. Siamese twins and circus performers Max and Isaac tour Europe, embodying the thematics of difference and otherness: How is it possible to live separately and yet forever side by side?

Nina Paavolainen

Out Into the World

In searching for a common denominator in Finnish literature from recent years, we strike upon a distinct openness among Finland’s younger mid-generation prosaists to reaching beyond the borders of Finland, and an effortless movement from one country and culture to the next. Control of form versus content is also stronger.

The western Estonian landscapes of Oksanen’s Purge shift to sub-Saharan Africa In Elina Hirvonen’s second novel Kauimpana kuolemasta(‘Furthest from Death,’ 2010). In this work, Paul, a Finn, and Esther, an African, take turns as the first-person narrator.

Katri Lipson’s Kosmonautti (’Cosmonaut,’ 2008) is set in 1980s Murmansk, another geographically and culturally distant locale. A schoolboy from a seedy Soviet suburb who is passionately in love with his teacher dreams of a future as a cosmonaut. Lipson’s prose lingers in the space between events and at the boundaries of human encounters with an exceedingly sure hand, and its forebears can be sought first and foremost in the Russian classics.

Kristina Carlson’s Herra Darwinin puutarhuri (’Mr Darwin’s Gardener,’ 2009) gravitates geographically to England and deals with ideological-historical themes of the 19th century. The main character is Charles Darwin’s gardener, and the life of the small village community is reflected through the perspectives of the book’s various subjects. Carlson’s work transplants the great questions of modern man to a Kentish kitchen garden.

Miika Nousiainen adds a tragicomic spin to our problematic relationship with our western neighbours in his book Vadelmavenepakolainen (’Raspberry Boat Refugee,’ 2007), whose protagonist is completely obsessed with becoming Swedish. Liberating laughter makes the obsession feel like nothing more than a twisted whim. The versatile Johanna Sinisalo’sBirdbrain (2008) pits a young couple against the forces of nature in New Zealand, whereas Leena Krohn’s entire crystalline oeuvre approaches philosophical essayistics.

It’s wonderful that the voices of immigrants are starting gradually to be heard and that the Finnish experience is growing more diverse. Writing competitions have traditionally been popular in Finland, as a way of winnowing out new talents for the publishers’ publishing programmes. 27 eli kuolema tekee taiteilijan (’27, or Death Makes the Artist,’ 2010) is a strong debut from the Slovakian writer Alexandra Salmela, one of the prize-winners from the What on Earth is a New Finn? writing contest. The work is not an immigrant novel per se, yet it offers a fresh perspective on contemporary Finnish culture.

The main character is Angie, a young art student from Prague, who is anxious to achieve stardom before her 28th birthday – after all, all of her idols from Jimi Hendrix on have died at 27. With the assistance of her professor, she travels to the Finnish countryside and meets all manner of wayfarers. The strengths of Salmela’s work are her masterful control of shifting registers and styles – seasoned with irony that pokes fun at everyone equally. The family’s youngest child’s stuffed pig also lends its voice to the commentary!

Family, Everyday Life, and Gender

One of the characters in Alexandra Salmela’s novel is a mother who wants to be the perfect enlightened woman and mother, with at-times tragicomic results. In recent years, depictions of family, everyday life, and gender roles have become more diverse in the hands of both female and male authors. These themes are linked to societal changes: the global economic recession, the stress on economic values in the greater societal debates, the increasing inequality of Finnish society, and the splintering values of our post-industrial world are all reflected in recent prose. For years, Pirkko Saisio has been one of the country’s premier literary commentators; her most recent novel, analysing contemporary Finland, is fittingly named Kohtuuttomuus(’Excess,’ 2008). And Anja Snellman, always sensitive to registering timely issues, has written about young Muslim women in Finland (Parvekejumalat, ’Balcony Gods,’ 2010).

Kari Hotakainen’s Juoksuhaudantie (’Trench Road,’ 2002) tells about a husband who, after being left by his family, decides to remodel his house, the veteran-built variety that symbolises a certain stoic masculinity, to get them back. He has done everything at home to please his wife and is at a complete loss. The setup is quintessentially Finnish: a man grits his teeth and undertakes, contrary to all voices of reason, to solve his marriage crisis through action. Hugely successful in Finland, the novel received the Nordic Council’s Literature Prize and was also made into a movie.Ihmisen osa (‘The Human Lot,’ 2009) portrays the downside of career- and status-focused ambition with Hotakainen’s characteristic laconic humour, and once again the woman and mother is often the ultimate fount of common sense.

Riikka Pulkkinen’s Totta (’True,’ 2010) is a structurally skilfully composed artistic novel in which the portrayal of the family is partially anchored in a depiction of the era of the 1960s. A grandmother and wife whose modern dedication to her career has been consistent from the start emerges as one of the novel’s main characters. Others have adapted to her ambition, and its effects on the family dynamics are deeper than she could have ever guessed. A nanny from the countryside who joins the family embodies the gap between rural and urban, which has only really been mediated by the boom generation born in the cities of the 1960s. Although a love triangle lies at the heart of the work, Pulkkinen at the same time hones in on the social ruptures of recent decades.

Mikko RimminenPhoto: Heini Lehväslaiho

One of the most heart-wrenching depictions of a middle-aged woman is Mikko Rimminen’sNenäpäivä (’Red Nose Day,’ 2010), a big success, in terms of sales and otherwise, the year it appeared. The main character is Irma, who, seeking companionship and friends, decides to masquerade as an interviewer conducting market research. Irma can be seen as a typical Finn who thinks more than she talks and whose shyness feels almost like rudeness. Yet Irma is the universal modern human: confused and lonely, groping for contact with others. Rimminen belongs to that generation of writers for whom the Finnish language is not simply a tool but itself an essential object of reflection: he originally debuted as a poet.

Markus Nummi’s Karkkipäivä (’Candy Day,’ 2010) is a depiction of a horrifying social case that results in the suffering of little girl. In this work, an overly highly-strung woman is the victim of her own ambitions. A central role in Nummi’s work is played by a young father and screenwriter baffled by his role both at work and at home. Uncertainty about others’ expectations drives him to near-paralysis.

Nina Paavolainen

Publishing in Finland in the 21st century

Brothers Touko (front left) and Aleksi (front right) Siltala of Siltala Publishing pose with some of their authors: Pirkko Saisio, Leena Lander, Kari Hotakainen and Hannu Raittila.Photo: Laura Malmivaara

In 2008, the brothers Touko and Aleksi Siltala founded Siltala Publishing, which publishes about 25 titles a year: slightly over half is literature and the remainder nonfiction, with about a quarter of all titles translations into Finnish. Both men have decades of experience in the publishing industry and agreed to respond to some questions about general developments in the field.

Nina Paavolainen: How have readers’ tastes changed? Is Finnish literature more popular than translated literature?

Touko Siltala: The situation has actually changed quite a lot over two decades. Total annual sales of books has remained more or less stable, but there used to be more room for translated literature. Translations of quality literature are read less often nowadays. Sales are steered more by publicity than literary criticism, and the fact that Finnish authors are of interest to the media and receive lots of exposure ends up having a significant effect on sales. Women’s and other periodicals do big pieces on authors.

Aleksi Siltala: These days, a lot of Finnish books are also made into movies, and they’re optioned quickly. That could also play a partial role in the interest in Finnish authors.

NP: What kind of nonfiction is published in Finland? What sells?

AS: Finns have always been interested in political history, especially the history of Finland and the surrounding region, as Sofi Oksanen’s success demonstrates. There appears to be a pretty solid group of readers interested in such topics. A lot of young people aren’t familiar with the Soviet Union, and they’re fascinated by the Cold War era. Many of the notable figures of the previous century, such as Finland’s long-term president Urho Kekkonen and marshal Mannerheim, continue to generate enthusiasm. On the other hand, I would say that earlier periods of Finnish history are reaching readers better, too. In addition, perspectives are gradually broadening; for instance, nonfiction works on China are on the rise.

NP: In recent years, a large number of authors have switched publishers. Allegiance to one’s publisher used to be, for all practical purposes, absolute. Does this say more about changes in the publishing field or about a shift in attitudes among authors?

TS: Authors born in the 1960s and ‘70s have a totally different concept of the relationship between author and publisher. Of course they’re still interested in a competent editor, but they want well-planned marketing and communications, too. The sale of foreign rights is an issue as well, but direct and immediate contact is the most important thing. Authors who debuted in the 1970s, for instance, had a completely different take on the matter: the relationship between publisher and writer was like a marriage, which for the most part meant being taken care of and getting sufficiently large advances. The fact that these days an author may have several publishers is a good thing. Independence is a positive thing for artists.

AS: Being accessible and present is important. Many authors want their publisher to act like a boutique publisher, where you get good service and answers and decisions rapidly.

NP: You two also have decades of experience with international book fairs and the international publishing field. Does it seem to you that interest in Finnish literature has grown?

TS: It has grown significantly. Finnish success stories, such as Arto Paasilinna and now Oksanen, have of course cleared the way, but the Nordic countries as a geographical area are also better known now. Foreign colleagues pick your brain for tips on Finnish literature, ask for new names and grill you for your opinions on prize-winners – this never used to happen. Now it feels completely realistic for a Finnish writer to be a really hot name.

AS: These days, as soon as you’ve covered what’s new at a fair, a foreign publisher might ask about Finnish authors in all seriousness. The interest is genuine, and it has grown wildly in recent years. The success of Nordic detective novels has sucked everyone else along in its wake.

Nina Paavolainen

Finnish poetry in the 21st century

Volumes of vital verses: Two hundred books of poetry are published each year in Finland.

At this particular moment, the most delightful domain of contemporary Finnish literature is our rich and vital poetry. For a language area of our size, almost two hundred works of poetry a year is an exceptional number of volumes. Important collections are published by small presses and various poetry collectives, as well as by established publishing houses. In addition, book-on-demand technologies and digital environments in general have made it economically feasible to produce poetry collections, specifically those of a collaborative nature.

In terms of their linguistic roots, Finns are a poetry people, and vaguely melancholic song is a classic self-portrait of Finnish self-expression. The Kalevala-style folk poetry still sung in cottages in the early 19th century is by no means a far-fetched forebear for many of the collaborative forms adopted in contemporary poetry. The rigidly formal evening recitals of the early decades of the 20th century have, in a hundred years, transformed into poetry sessions popular especially among the young: jams at which stage poetry – spoken, sung, or presented via multimedia – is seen and heard.

Poets also tour the country, presenting their poems themselves: for instance, Heli Laaksonen, who writes in the Laitila dialect, always attracts enormous audiences at her appearances, in addition to achieving print runs of up into the tens of thousands.

Television has picked up on poetry as well: a popular show called Runoraati (‘The Poetry Panel’) has held onto its programming slot for years. The format of the program is as Finnish as could be and completely unique. Poets present their freshest texts through well-produced poetry videos, and a changing panel of nonprofessional judges analyses and playfully awards points to what they see and hear. It’s almost impossible to come up with a better way introducing broad audiences to new works of low-circulation literature.

The poetry boom of the 21st century offers a fascinating glimpse into how the field of poetry has remained a home base for younger generations of Finnish writers and readers. It is also, in a way, the ‘introductory genre’ to getting published, the genre in which younger – these days, those born in the 1980s – authors often debut. Later they may pick up other genres as well, and it is common for Finnish authors of different generations to be concurrently publishing both prose and poetry.

The genres of contemporary poetry reveal how those most actively involved in its creation – those born in the 1970s and ‘80s – represent a generation that has been immersed in information technology. Various internet-facilitated methods and digital platforms are used as the basis for creating poetry, and the concept of found objects, familiar from the visual arts, is realized, for instance, through the use of search engines. Browsers gather material from the world of online speech and language for the poet to work with. The poets Henriikka Tavi, Teemu Manninen, and Harry Salmenniemi, for example, have all demonstrated this type of interest in the materiality of language.

It’s clear that many modernist conceptions about poetry have been hard pressed in the hands of 21st-century artists. As a matter of fact, the younger generation of the 1990s had already made a pronounced departure from the pure modernism of the 1950s: Helena Sinervo, Jyrki Kiiskinen, Jukka Koskelainen, Tomi Kontio and Riina Katajavuori forcefully foregrounded efforts in contemporary poetry to challenge the modernist tradition and its form, imagery, and notions of subject. Their generation also demonstrated a clear attempt to write out poetic concepts explicitly for debate, as well as to bring about the mutually supportive communities in which the youngest generation of poets now works.

Today, in the 21st century, most debate takes place online. High-quality literary journals are published in Finland, but there is no question that the most interesting discussions, those most eagerly seeking newness, can be read in the blogs of various writers and critics, the best of which embody demanding essayistics in terms of substance.

Saila SusiluotoPhoto: Pekka Holmström

American-influenced language poetry and post-structuralism have acted as an inspiration for many poets of the youngest generation. Yet many of the young poets of the 21st century continue to approach modernist expression through new perspectives, and at this moment the poetry field is dominated by a positive fragmentation and the spirited debate this entails.

Language is not thus, the only ‘theme’ of poetry; many of the issues of the postmodern world and lifestyle, from the individual perspective, emerge in poetic works. For instance, the pervasiveness of contemporary visual culture has been a motif in the poems of Eino Santanen: in his works, he has critically examined the way in which the media and advertising language have established themselves as a direct continuation of our senses.

An interesting perspective on 21st-century poetry also opens up from the poetry written by young women, whose relation to their own biological sex and, for instance, motherhood is seen, in contrast to the traditions of women’s history, through affirmation. As late as the 1980s, representations of women in Finnish literature were full of the biological burden and grievances of the second sex, but today Saila Susiluoto, Johanna Venho, Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen and Juuli Niemi write about being a girl and a woman boosted by a strong female identity. The title of one of Huotarinen’s collections, Iloisen lehmän runot (‘Happy cow poems,’ 2009), reveals that 21st century Finnish poetry resounds with the laughter of women as well.

Mervi Kantokorpi

Finland-Swedish literature

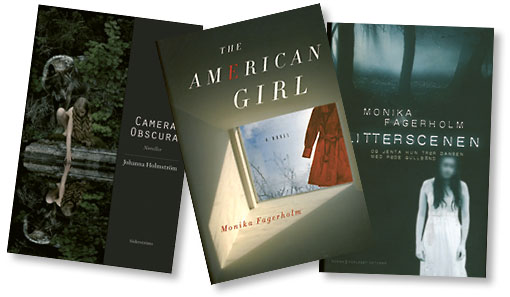

Eco-terrorism in Helsinki figures in Johanna Holmström’s Camera Obscura, while Monika Fagerholm’s Glitterscenen (The Glitter Scene, right) is a follow-up to The American Girl (centre). Fagerholm is one of Finland’s most translated authors.

Literature written in Swedish within Finland has a life of its own: only a small proportion of the 200 or so books published each year are translated into Finnish, and even fewer find their way into bookshops in Sweden. Literary fiction is published by a handful of publishers, while non-fiction has more outlets, both through professional publishing companies and highly localised organisations.

Literature written for a market of approximately 300,000 people is only in very rare cases commercially viable, which means that publishers are dependent on the sale of educational materials and on the financial support of various private foundations that between them have access to capital far in excess of that available to the Nobel Foundation.

The use of these funds to support literature written by and for a minority goes unquestioned: literature, together with Swedish-language radio and television and a large number of daily newspapers, is an important means of both protecting and developing the language that is the cement holding the minority together. This is one way of describing a small literary culture in sociological terms.

But there must also be other factors that enable it to retain its vitality. It has to have some sort of aura, a sense of self-awareness that makes it an attractive vehicle for the artistic ambitions of new generations. What follows is intended to give an outline of just some of the recurring characteristics that differentiate Finland-Swedish literature from the mainstream literature of both Sweden and Finland.

The joyous experiment

Hannele Mikaela TaivassaloPhoto: Cata Portin

Many people believe that the 1910s and 1920s were the golden age of Finland-Swedish literature, inspired by the experimental mood elsewhere in eastern Europe. The multilingual Edith Södergran, raised in cosmopolitan St Petersburg in the early years of the twentieth century, introduced passionate, Nietzschean poetry that eschewed rigid formality.

At the same time, she also introduced androgyny: ‘I am a neuter, a page, a bold resolve’, a declaration that continues to echo through the young women writers of the twenty-first century. In her novel Diva (1998), Monika Fagerholm introduced an updated and boldly boundary-transgressing young female character into Finland-Swedish literature, depicting a girl who actively pursues her own interests and refuses to be bowed by convention.

Similarly bold young women can be found, for instance, in the work of Hannele Mikaela Taivassalo (Fem knivar hade Andrei Krapl / The Five Knives of Andrei Krapl, 2007), Catharina Gripenberg (På diabilden är huvudet proppfullt av lycka / On the Transparency My Head is Completely Full of Happiness, 1999, and Ta min hand, det vore underligt / Take My Hand, It Would Be Strange, 2007), Eva-Stina Byggmästar (the ‘Happiness Trilogy’, 1992-97), Ulrika Nielsen (Mellan Linn Sand / Between Linn Sand, 2006,) and Mikaela Strömberg (De vackra kusinerna / The Beautiful Cousins, 2008).

Another characteristic shared by these books is that their form, whether narrative or poetry, is aesthetically driven: traces of realism are rare, cause and effect remain unexplained, and different time periods glide into each other. They also share an almost impudently curious attitude.

Reading these books is like being immersed in self-contained worlds, with their own laws, where deep-felt emotion is woven into the texts, and which manage the rare accomplishment of arousing strong feelings in their readers.

An absence of crime and love

Kjell WestöFinnish literature goes further than ever

Although there is a strongly expressive, emotional tradition running through the whole of modern Finland-Swedish literature, there is simultaneously also a striking absence of the established formats for emotionally charged literature.

Finland-Swedish literature rarely deals with murder, sex or love, common themes in literature the world over. There is very little crime-fiction in Finland’s Swedish-language literature, and sex scenes appear approximately once a decade. Even the traditional love-story and romantic fiction have failed to become established formats.

It is therefore hardly surprising that in 2011 one of the two big Finland-Swedish publishing houses announced a novel-writing competition in which they are specifically looking for novels with ‘intrigue’, and that a senior editor has gently pointed out in an interview that a novel is more than a linguistically intricate work of art, and that it is no bad thing if it also contains an enticing plot.

To put it rather more bluntly: the publishers need authors who can write books that merit large print-runs, because very few Finland-Swedish authors can be counted as bestsellers. The only author of the past few decades who has regularly delighted both critics and the book-buying public is Kjell Westö (b. 1961). It isn’t hard to see why: he sticks close to reality, creates long narrative arcs with interwoven tensions between characters, and he has a unique voice which helps his readers stay faithful from book to book.

For a great many readers he has become a highly appreciated chronicler of the changing face of Helsinki throughout the 20th century. Two other writers who have consistently succeeded in appealing to both critics and readers over many years are Ulla-Lena Lundberg and Lars Sund. They have both turned to the early twentieth century for points of tension in the development of society, as well as providing compelling characters for their readers to care about.

These three, together with Monika Fagerholm, are among the authors who would attract readers in any country. Monika Fagerholm is the first Finland-Swedish author to be awarded the prestigious August Prize in Sweden, and also the first to have been recommended by Oprah Winfrey. She is one of the most translated authors in contemporary Finland-Swedish literature.

A life alongside reality

At the start of the 2010s a new phenomenon is beginning to define itself: a form of text that blends experimentation with realism.

Some of the authors of the younger generation have started to create hybrid forms in which strict realism suddenly and unexpectedly opens out to encompass supernatural phenomena. The romance of Gothic horror, medieval creatures and spectres have been appearing in student flats, city apartments and cruise ships.

One of the strongest young voices belongs to Johanna Holmström, who, in her collection of linked short stories, Camera Obscura (2009), depicts young eco-terrorists in Helsinki, but allows the narrative to glide into obsessions that become almost archaic tropes: the wolf is a recurring motif, the beast that is dangerously and painfully attractive. Stefan Nyman’s debut novel, Anna är online (Anna is Online, 2008), also provides a realistic depiction of student life and young relationships, while black crows are portents of Edgar Allan Poe’s menagerie of horrors, or perhaps the limitless fears of a fragile mind.

Similar cracks between a comprehensible reality and a world tinted by messages from beyond the rational sphere can be found in the relatively small number of authors writing for younger readers in recent decades. Henrika Andersson (b. 1965) and Maria Turtschaninoff (b. 1977) have both used their books to show how different realities can affect each other. An inexplicable world speaks to the young protagonists, reflecting reality through figures drawn from a long history of folklore.

These books are perhaps reflections of the global boom in fantasy literature, but they also feel like natural successors to Tove Jansson’s tales from Moomin Valley and the gentle stories of grande dame Irmelin Sandman Lilius, where low-key characters in small towns set in an unspecified period experience astonishing things.

Realism is certainly not a word that can be applied to Finland-Swedish fiction – but perhaps that is the paradoxical strength of this minority literature: it creates its own worlds, worlds that are universal and deeply loved by a secret fan-club with members stretching from Uruguay to Japan.

Maria Antas, project manager and critic

Selection of literary links

Association of Finnish Non-Fiction Writers

Books from Finland

Booksellers Association of Finland

FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange

Finnish Book Publishers Association

Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature

Finnish Literature Society

Finnish Whodunnit Society

Helsinki City Library

Lahti International Writers’ Reunion

Modern Finnish Writers

National Biography of Finland

Swedish Literature Society in Finland

Union of Finnish Writers

Society of Swedish Authors in Finland (In Swedish)