Finnish mobile games have taken the world by storm, and there’s no end in sight for the growth of the local games industry, which is set to bypass the one-billion-euro benchmark in total turnover before 2020.

The national bird of Finland may be the whooper swan, but around the world a very different sort of Finnish fowl has become famous. The Angry Bird, created by Finnish developer Rovio Entertainment, has become one of the most internationally recognisable video game icons of the 21st century. The phenomenal success of Rovio’s franchise is far from a fluke however, as Finland hosts one of the most active and rapidly expanding video game industries in the world.

The amount of Finnish games companies has exploded in the last two years. Of the 150 companies active in the field in late 2012, as many as 40 percent are startups established in the last two years, according to figures released by Neogames, the Centre of Game Business, Research and Development. The total projected turnover of the industry in 2012 is 250 million euros, almost three times as much as three years earlier. If growth continues at the current rate, the projected total turnover for 2020 is a staggering 1.49 billion euros.

Pressure on the midfield

Developing large-scale titles “demands a very specific set of professionals and resources,” says Bugbear’s Joonas Laakso. Photo: Bugbear

The heart of the Finnish game industry is Helsinki and its environs, which are home to some 50 companies. Here are the developers of the largest games made in Finland, such as Remedy – famous for the international brands Max Payne and Alan Wake – and Bugbear, which recently completed the development of Ridge Racer: Unbounded for Playstation 3, Xbox 360 and PC.

According to Bugbear producer Joonas Laakso, the new Ridge Racer is the second-largest development project ever undertaken in Finland, involving 100 developers in Finland and other countries and lasting almost two years. Projects of this scale are rare for a reason, explains Laakso.

“The development of large-scale triple-A titles demands a very specific set of professionals and resources,” says Laakso. “Even for a studio of our mid-range size, it can be difficult to find capable people from within Finland.”

According to Laakso, developers of Bugbear’s size are feeling the squeeze from larger studios in the global market. “Major franchises such as Assassin’s Creed and Call of Duty are dominating both release schedules and marketing,” says Laakso. “The situation may change with the coming of a new generation of games consoles.”

Attack of the apps

This archer contributes to the melee in Clash of Clans. © Supercell

The engine of the Finnish games industry is found in the mobile games sector, as a clear majority of companies specialise in mobile platforms. The reasons for this are clear, according to the Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation (known by its Finnish abbreviation, Tekes).

“The cost of building a mobile game is often only a tenth of the budget of a triple-A production,” says Kari Korhonen, head of Skene, the Tekes programme aimed at supporting the games industry. “It’s been easier for small developers to invest in mobile development.”

A rising star is Helsinki-based Supercell Games, a 70-employee firm whose game Clash of Clans has ranked first of top grossing apps in Apple’s iOS Store in 77 countries. The financial success of the game is based on a free-to-play model, where revenue is generated from in-game microtransactions by the players.

“Our team wanted to create a strategy game that would be easy to pick up and play and attract wide range of players around the world,” says team leader Lasse Louhento. “We are really surprised about how popular the game has become and how passionate our fans are about it.”

App rep

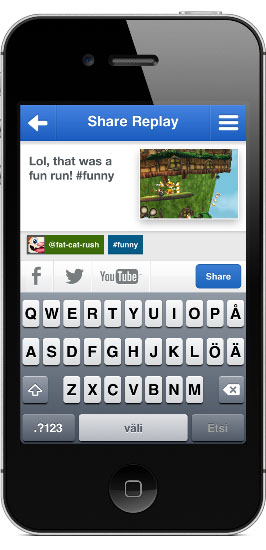

One of the functions of Applifier’s Everyplay service allows you to share replays of your games on social media.Photo: Applifier

Another upcoming firm in the field is Finnish startup Applifier, which aims to connect game developers for Facebook and mobile platforms to their audiences.

Olli Sinerma, producer of Applifier’s mobile game discovery service Everyplay, believes the reason for the rise of Finnish mobile developers is the spread of digital distribution services such as the App Store.

“Finland has a long standing in the global game industry, but the digital distribution revolution made it easier for us to get to the global market, something which was very difficult back in the old days of ‘bricks and mortar’ game shops,” says Sinerma.

He also names further reasons for Finnish success in the mobile market: a tech-savvy population, mobile know-how inspired by Nokia and a high level of national education.

Institutions change slowly

Big action: Bugbear’s new Ridge Racer: Unbounded forms the second-largest development project ever undertaken in Finland. © Bugbear

The growth of games as a medium has slowly garnered academic interest. According to Professor Frans Mäyrä, head of the University of Tampere Game Research Lab, a new gamer generation of researchers brought a boom of activity to the field in the early 2000s, but it did not last.

“After a few years people realised that institutions still change rather slowly and that there were still only a few paid academic positions available in game studies,” explains Mäyrä. “Finland is one of the countries at the forefront of this development, yet there is clearly need for more permanent funding and positions in this field.”

Universities have not been the only institutions slow to pick up on the significance of games, says Mäyrä. “The government has been slow to react to the possibilities of games,” says Mäyrä, “and several countries have gained a competitive advantage through systematic subsidies and other benefits to game companies.”

The future of Finnish games, Mäyrä believes, lies in the ongoing shift towards digital distribution and free-to-play models:

“The rise of mobile games and the growth of entire ecosystems where gaming experiences go beyond device boundaries are also trends that are going to change the landscape of gaming and game development in the future.”

By Lassi Lapintie, January 2013