Finland’s Parliament adopted a declaration of independence on December 6, 1917. Prior to that, armed “security” groups, which later became known as the Whites and the Reds, had already formed.

The Whites were politically conservative, while the Reds were associated with the labour movement. The long-established discord between the two camps meant that, even after independence was achieved, the way ahead for the new nation was unclear.

The Civil War lasted from January 27 to May 15, 1918. Out of some 36,600 deaths, approximately 9,700 were executions and 13,400 were due to appalling prison camps. Red casualties outnumbered White by around six to one.

Political reconciliation began almost immediately after the war was over. It would take longer for cultural and social reconciliation to begin.

Moving towards a more inclusive republic

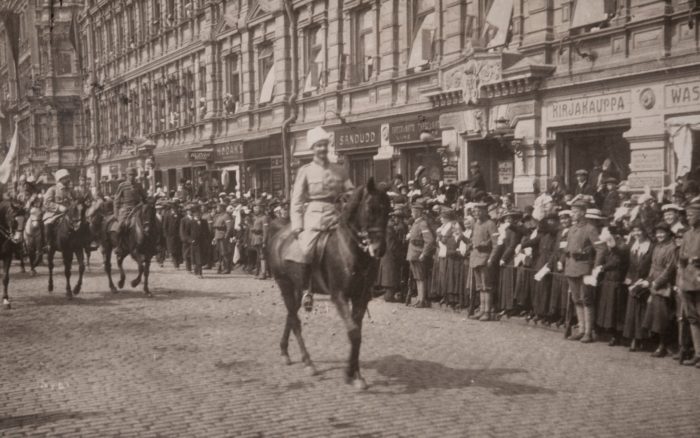

The White general, C.G.E. Mannerheim, leads a parade down the Esplanade in Helsinki on May 16, 1918 in honour of the end of the Civil War.Photo: cc by 4.0/Helsinki City Museum

The White victors had placed their hopes in a monarchy with strong ties to Germany, but that country’s eventual defeat in the First World War put an end to the idea. Finland chose a republican constitution in July 1919.

“It is hard to talk about republicans being more interested in compromise when many of them supported harsh measures against Red soldiers,” says Jason Lavery, permanent adjunct professor at Helsinki University and professor of history at Oklahoma State University. “Yet, those who wanted a republic saw it as a more inclusive form of government for both the moderate left and monarchists.”

Finland’s first president, K.J. Ståhlberg, was a believer in reconciliation, pardoning Red prisoners, allowing trade unions to negotiate and signing a law so tenant farmers could purchase their holdings at advantageous prices.

“Ståhlberg did try to unify the country, but within the parameters set by the anti-Marxist consensus,” says Lavery.

Post-war moderation

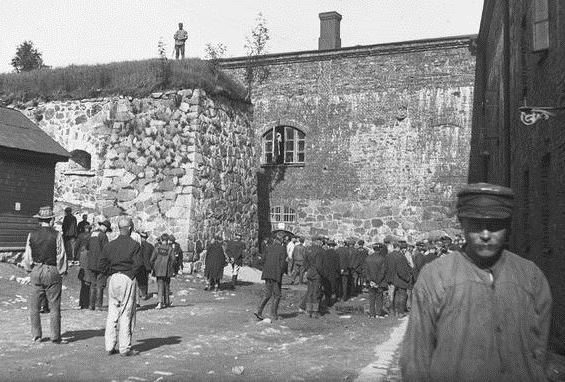

Helsinki’s island fortress of Suomenlinna, now a Unesco World Heritage site and tourist favourite, was the location of a prison camp holding captives from the Red side in early 1918.Photo: Niilo Toivonen/cc by 4.0/ Finnish Heritage Agency

The moderate Progressive Party and the Agrarian Union supported compromises and steps towards reconciliation during the early years of independence. The extreme left was excluded from the political process, but the Social Democrats were welcomed in local politics, and even became the largest party in Parliament under the leadership of Väinö Tanner.

“Tanner did what he could,” Lavery says. “As prime minister in 1927, he accepted the salute of the Civil Guard, the militia that formed much of the White Army, in the annual parade commemorating the end of the war.” The White general, C.G.E. Mannerheim, had begun an annual tradition of a parade on May 16 in honour of the end of the Civil War.

Tanner’s acceptance of the salute was particularly relevant, because the Civil Guard had been called butchers by the left because of their role in summary executions. When elements of the Civil Guard and a group called the Lapua Movement attempted a right-wing coup, in 1932, the majority of Finns rejected them and the uprising failed within days.

The late 1930s was a period of relative economic prosperity and continuing social reforms, which helped to contribute to a strong democracy and parliamentary system.

Bringing people together

Miina Sillanpää, who would become known for her ability to get parties with opposing viewpoints to converse, gives a speech as a member of Parliament in 1907.Photo: J. Indursky/cc by 4.0/Finnish Heritage Agency

Another politician who was influential in forming the future of the country was Miina Sillanpää, known as a bridge-builder who could bring together parties with opposing viewpoints. She was among the first women, 19 of them, voted into Parliament in 1907 after women gained the right to vote and to run for office, in 1906. During the Civil War she worked to help orphaned children, of whom there were many – 15,000 by some estimates.

In Tanner’s government (December 13, 1926 – December 17, 1927), she held the position of Second Minister of Social Affairs, making her the first female government minister in Finland. She came from a working-class background and helped drive social issues such as better working conditions for maids and other workers, and shelters for orphans and unwed mothers. Tarja Halonen, Finland’s president from 2000 to 2012, has remarked of Sillanpää that she “can be said to be one of the mothers of the welfare state.”

Sporting heroes, most notably distance runner Paavo Nurmi, also helped all Finns to root for a common goal. He won 12 Olympic medals – nine gold and three silver – over three Olympic Games between 1920 and 1928.

Together in the Winter War

In the Winter War of 1939–40, recruits from Vihanti, a village about 600 kilometres (375 miles) north of Helsinki, sit during a break in the fighting at Suomussalmi, near the eastern border. The Winter War became the unifying, unambiguous war that the Civil War was not.Photo: cc by 4.0/Finnish Wartime Photo Archive

In 1939 the Soviet Union attacked Finland, starting what is known as the Winter War, which lasted from November 30, 1939 to March 13, 1940 and united all elements of Finnish society in the defence of their country.

“The Winter War was the unambiguous and heroic war of national liberation that the Civil War was not,” Lavery says. “It was independent Finland’s first great collective achievement.”

Organisations representing employers and employees agreed to negotiate and cooperate. The Social Democrats encouraged their members to join the Civil Guard. Commander-in-Chief Mannerheim cancelled the annual parade commemorating the White victory, replacing it with a day of remembrance for the fallen. Finns were willing to unify for a common cause.

“One must also consider events after the Second World War,” says Lavery. “These include the legalisation of the Finnish Communist Party, the building of the universal welfare state, and the art and scholarship produced about the events of 1918.”

Reconciliation is never over

The Civil War brought destruction to many parts of Finland. In April 1918, only chimneys were left standing in Tammela, an area of the central western city of Tampere.Photo: cc by nd 4.0/Vapriikki Photo Archive/Tampere Museum

One of the most important literary works related to the Civil War is Väinö Linna’s trilogy Under the North Star, published in 1959, 1960 and 1962. It sympathetically explores the motivations of the Reds and unflinchingly describes what happened in the war’s aftermath.

It was the cultural reconciliation Finland had long awaited, but the process of reconciliation is never over. “Civil wars often never really end,” says Lavery.

Even today, Mannerheim remains a divisive figure. “Butcher” is sometimes spray-painted on statues of him, while the Mannerheim Museum uses the loaded term “War of Liberation” to refer to the Civil War.

A 2016 survey by Finnish national broadcasting company Yle shows how deeply the war affected people. Even nearly a century after Civil War ended, 22 percent of respondents said that it remained a “highly sensitive” topic in their families.

Yet Finnish society values a process of law, democracy and working together for the common good. This has helped heal, as much as possible, the scars from the Civil War.

“It took decades to gain full trust in democracy,” said Finland’s President Sauli Niinistö in a speech on January 1, 2018. “Participatory patriotism was born.”

One lesson that came out of the Civil War, he said, is that “there is diversity, people have different backgrounds, convictions and goals, and we have a right to disagree. This is something we must be able to respect, however differently we ourselves might think.”

By David J. Cord, May 2018

Partial list of sources consulted

|