“Husu” first came to Finland in the 1990s as a Somali teenager. After overcoming obstacles in integrating, he has become a spokesman for the immigrant population.

Journalist, interpreter, politician, social pedagogue – Abdirahim “Husu” Hussein is a man of many roles but there is one main reason that he gets out of bed each morning:

“To make the world a better place,” he declares. “I’m changing one person at a time. But before I change anyone, I change myself; it’s about being a better human being every day. If I find a piece of glass lying on the street I make sure I remove it, so it won’t bother people that are coming after me.”

This is an apt metaphor for the more than two decades he has lived in Finland.

Journalist, interpreter, politician and social pedagogue Abdirahim Hussein has gradually emerged as a spokesman for the immigrant population in Finland since arriving here from Mogadishu 22 years ago. Photo: James O’Sullivan

Hussein has gradually emerged as a spokesman for the immigrant population here since arriving from Mogadishu as a teenager. Not content with being a passive newcomer, he remains adamant that regardless of age, country of birth, religion, mother tongue or profession, everyone in Finland must be treated as individuals.

Overcoming obstacles

Back in 1994, settling into life in the Turku region posed a considerable challenge for Hussein. Then, Finland was emerging from an economic depression, with its homogeneous population ill-prepared for integrating the refugees that had begun arriving on its doorstep.

It didn’t help that society’s minority fringe began loudly channelling their misguided frustrations in the direction of these newcomers.

Yet, in the face of such adversity, Hussein saw his new country of residence as a land of opportunity.

Almost everything you needed was here, as long as you were a part of the system,” he recalls. “Coming from a place that never had this, it was a shock – studying for free, getting medical for free, having a house and rights, and being able to speak your mind without being prosecuted.”

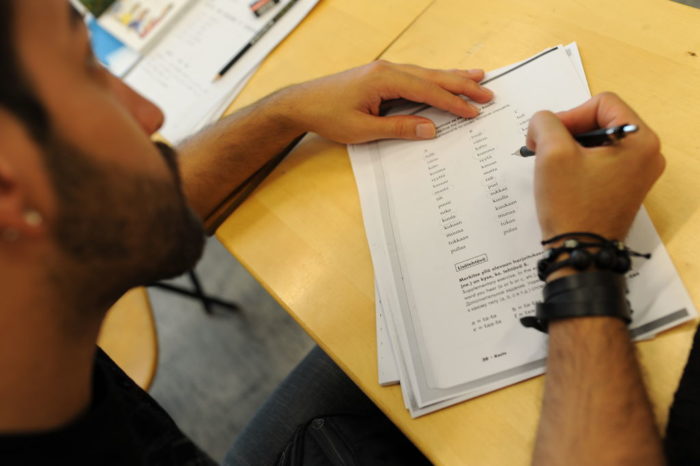

According to Abdirahim Hussein, the key to getting his own voice heard and landing his first job was to speak Finnish. It was not an easy path, but it was worth it.Photo: Emilia Kangasluoma

Hussein quickly realised he would first have to speak the local language before his own voice would be heard.

“I learned Finnish more by talking and having friends and reading books than going to class,” he recalls. “But it was a very hard process; it is still very difficult to master the language.”

Hussein’s linguistic skills helped him to land his first job, a summer post for students caring for the elderly. It was eye-opening for him to see society’s oldest members left in the care of others, in contrast to the family-orientated community that he grew up in.

Whilst some might find such cultural differences difficult to reconcile, Hussein nonetheless was determined to be an active member of society, eventually adding kitchen hand, waiter, cleaner, salesman and taxi driver to his resume, and going on to study social sciences at university.

Time to talk

Much of Hussein’s success is attributable to his headstrong approach. However, when looking at his fellow immigrants, it was clear that not all were integrating as well as he. Hussein recognised that he had to do something about this.

“If you want to make the world a better place, the first thing you have to have is some kind of political power,” he says.

Hussein entered the political arena in 2005 as a member of the Centre Party. Setting out to show that there was a place for everyone in Finland, Hussein emphasised that he, like his fellow “new Finns,” could also not be easily categorised. Alongside being an African, he was also a Muslim, a father, a heterosexual and a meat eater – not merely an “immigrant.”

Hussein subsequently found another prominent avenue for engaging the public in lively discussion, teaming up with comic Ali Jahangiri for the weekly radio programme Ali ja Husu (Ali and Husu). Approaching Finnish society and phenomena from the immigrant perspective, the duo filled the nationwide airwaves with humour and insight for 3 and a half years, before eventually stepping away from the mic in 2016.

Pure happiness

Meanwhile, Hussein has remained active in numerous community projects. Perhaps the most notable of these is Moniheli, the immigrant-run NGO he cofounded, which brings multicultural organisations together to further their interests.

The ways of integrating immigrants to Finnish society have changed a lot since Husu Hussein came to Finland in the 1990s. Here immigrant children are getting familiar with winter and snow by taking part in cross-country skiing lessons. Photo: Otto Ponto

He has also begun expanding his sphere of influence by helping to export Finnish knowhow, bringing local goods and services to East Africa as a junior consultant for Finnish Consulting Group.

And so, amidst this tireless trailblazing, one wonders what Hussein does to unwind, exactly.

“My family relaxes me the most,” he says without hesitation. “I don’t have the luxury of taking them around the world, but we are happy with what we have.”

By James O’Sullivan, June 2016

Seeking asylum is a long processThe amount of people seeking asylum in Finland increased enormously in 2015, from 3,651 in 2014 to 32,476 in 2015. In 2016 there were 2,628 asylum seekers between January 1 and May 1. In 2015, most asylum seekers came from Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia. Applying for asylum in Finland is a long process. In 2015, asylum applications were processed, on average, in 284 days. There are over 21,000 applications under way at the time of writing, so it is impossible to predict how long the processing will take in the future. In 2015, according to the Finnish Immigration Service, a total of 7,466 decisions were made concerning asylum seekers. 1,628 seekers were granted asylum, 251 other residence permit, 1,094 were refused. Thousands of asylum seekers have returned voluntarily, mostly to Iraq and Afghanistan. You may seek asylum if you have a well-founded fear of being persecuted in your home country. The Finnish asylum application procedure is explained here. If you are allowed to stay in Finland, you will receive a residence permit card and be placed in a municipality. If you are not allowed to stay in Finland, you must leave Finland and the Schengen Area. |