Do you consider video games to be art? Experts on the subject certainly do.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum, New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London are only a few of the many distinguished institutions that have chosen to include video games in their art collections in the past decade.

And why shouldn’t they? Games are the joint result of tremendous artistic effort by illustrators, animators, screenwriters, composers, designers and directors, woven together by the skilled hands of programmers.

More importantly, they often have just as much to say about the world around us as any Coppola film or Dalí painting. Today’s game developers boldly tackle tough subjects from childhood cancer to gender inequality and strive to evoke deep emotion in their audiences.

“I’m very passionate about the idea that what we’re making is art. Our creative ambitions are high and artistic expression is an important focus point for all our projects,” says Sam Lake, born Sami Järvi (järvi means “lake” in Finnish), creative director of the Finnish game studio Remedy Entertainment.

Art comes in many forms, from masterwork paintings to music, but Lake’s personal specialty is storytelling. Remedy is globally known for narrative-driven games that purposely push the boundaries of the video game format.

“The way games tell stories is what makes them unique as a medium and an art form, because the player gets to be an active participant in them,” he explains. “A good story is a good story, regardless of the medium, but a video game involves the player in it.”

Early endeavours

When Sam Lake began his career at the turn of the millennium, the games industry was in a very different place.Photo: Remedy Entertainment

To some, the fact that video games even have stories may come as a surprise. In the space of only a few decades, games have evolved from simple tests of reflex to cinema-worthy experiences brought to life by near-photorealistic replicas of Hollywood stars.

Those who dismissed the adventures of Super Mario as child’s play in the 1980s might simply not have been paying attention to what’s been happening since.

When Lake began his career at the turn of the millennium, the games industry had barely graduated from Mario-style pixel graphics to rudimentary 3D. Back then, fully animated cutscenes and vivid storytelling were resource-intensive and hard to pull off.

“Audiovisually, video games were pretty clunky at that point in time,” he says. “We could attempt to tell complex stories, but the lack of artistic precision affected the emotional impact we could make on the player.”

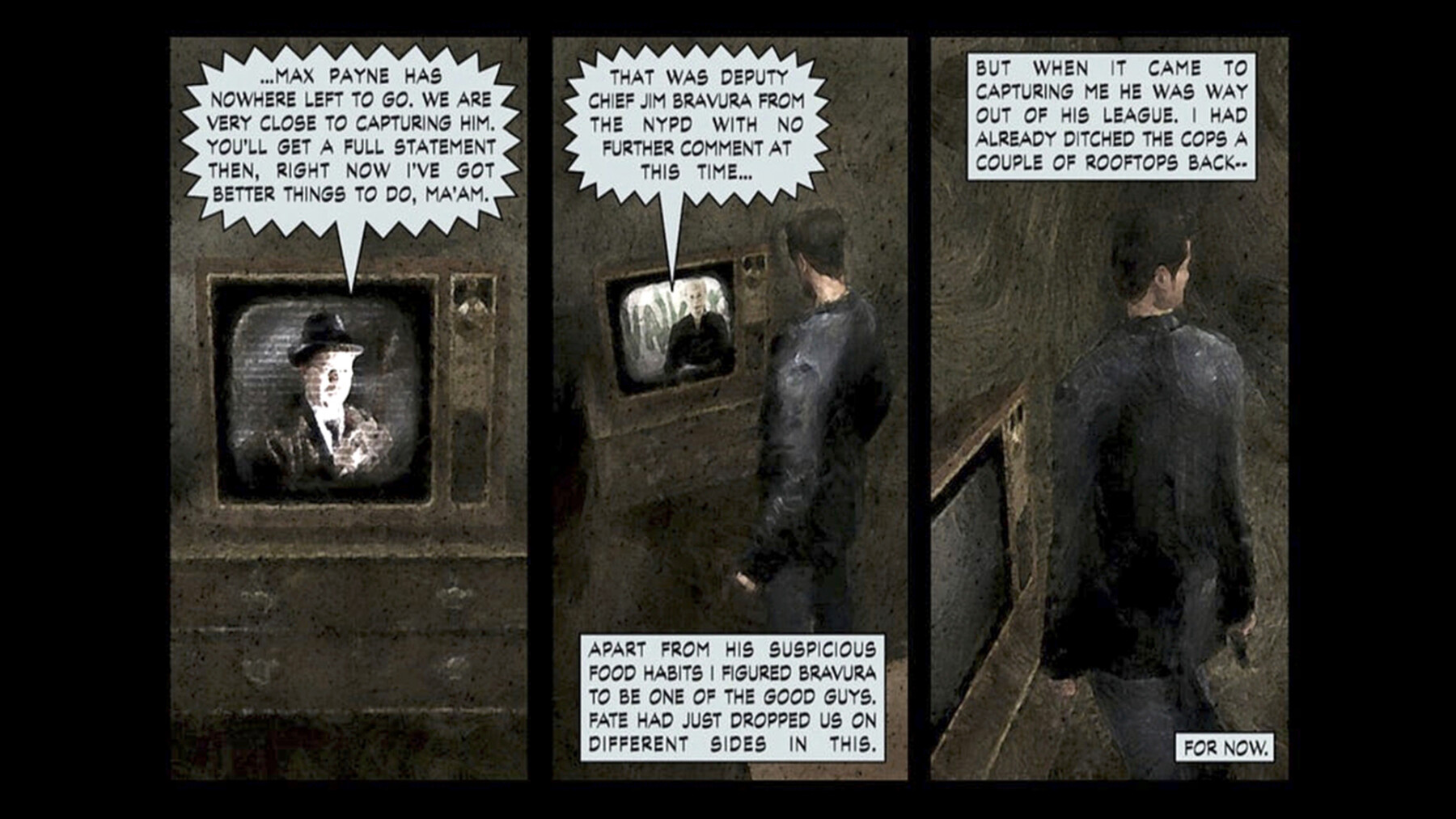

With Remedy’s first global hit, Max Payne, in 2001, Lake nevertheless wanted to find a way to weave a dark, adult tale about a detective out to avenge his dead family. In place of animation, the studio ended up using stylised comic book panels. This was one of Lake’s first forays into storytelling that deliberately oversteps the borders of different kinds of media – an approach Remedy still favours.

“I’ve always wanted to bring something new into the mix and shake up the industry a little bit. To me, that involves breaking the barriers between different forms of art,” Lake says.

High risk, high reward

This storyboard shows a scene from Max Payne, Remedy’s first global hit, released in 2001.Photo: Remedy Entertainment

The studio’s newest game, Alan Wake 2, tells the intertwining stories of the titular character, an author trapped in a dark nightmare dimension, and Saga Anderson, an FBI agent investigating odd occurrences linked to Wake’s disappearance.

On top of traditional action gameplay, it includes 90 minutes of live-action video material, songs that comment on the game’s plot, custom-made street art and photography, a choreographed musical sequence and snippets from two different novels.

“We worked really hard to bring together different forms of expression in the game. They all intertwine to create a virtual world that comments on the nature of art and how it affects reality,” Lake says.

Although technology has come a long way from the early 2000s, the undertaking still came at a cost. Released in October 2023, Alan Wake 2 is regarded as one of the most expensive cultural productions in Finnish entertainment history.

Thankfully, the game has drawn a feverish response from critics and gamers alike, with TIME magazine even naming it Game of the Year in 2023. Lake himself recently became the first Finn to ever be included in Variety magazine’s annual list of the 500 most influential people in the global entertainment industry – due in large part to his “penchant for narrative finesse.”

“The game has been received wonderfully, even by people who don’t really play games. All the way back in 2010, when the first Alan Wake came out, we heard from people whose non-gamer spouses would not let them play solo because they were so invested in the game’s story,” Lake says.

It’s all about the interaction

Telling a tale in the form of a video game is not as straightforward as simply drawing up a script and animating it. Tying a multilayered, labyrinthine narrative together with interactive gameplay mechanics is an art in itself.

“While interaction is what makes games so interesting, it is also their biggest hindrance. The hardest thing is making sure we’re telling a story that makes sense for interactivity,” says Molly Maloney, narrative designer at Remedy.

“A writer could come to me with a scene where two characters have an argument while the player watches. And that is not a game, that’s a movie! My job would be to figure out how to give the player agency,” she explains.

Maloney’s job description is still fairly new within the industry, but she sees it as a natural extension of the evolving role of storytelling in games.

“You no longer need to make the argument that story matters. We now have story modes even in football and racing games, because they allow people to roleplay.”

Games that make you cry

“One of the most exciting things about designing mysteries is that you can make some of the information hard to find,” says narrative designer Molly Maloney.Photo: Remedy Entertainment

In the early 2010s, Maloney worked at Telltale Games, an American game developer devoted solely to narrative adventure experiences. Their games were mainly based on popular entertainment licences, such as The Walking Dead and Back to the Future.

Telltale’s works were largely stripped of traditional mechanics like driving and combat, and focused instead on moral choices and character development. Through this approach, they managed to reach wide, unconventional audiences.

“They showed players that a video game could make you cry,” Maloney says.

While the player could directly affect the plot of Telltale’s games with their choices and actions, leading to different kinds of adventures and endings, many other video games tell stories that progress linearly from start to finish. That is where things get tricky for Maloney and her fellow designers.

“With a linear story like Alan Wake 2, we have to find other ways to give agency. In that case, it is all about designing the story from the ground up so it has a lot to unpack and keeps the player thinking. Mystery is a great genre for that.”

In Alan Wake 2, the player alternates between Wake’s and Anderson’s points of view, and many of the game’s mechanics are tied to these characters’ skills and strengths. As FBI agent Anderson, the player collects clues and interrogates witnesses. During Wake’s sections, the author can physically influence and shape his surroundings with his writing.

“When it comes to games, one of the most exciting things about designing mysteries is that you can make some of the information hard to find. Of course, there is a minimum viable experience that the player needs in order to not feel confused about the story, but we can reward them for exploring and investigating,” she says.

In other words, every player experiences the story slightly differently. The more effort you put into immersing yourself in the world of Alan Wake 2 – or any other video game – the more you get out of it. As Maloney puts it:

“Finding a hidden clue or catching on to information that could have just gone sailing by makes people feel special. Video games manage to do that in a way that film, television and books can’t really replicate, and that is part of what makes them so unique.”

| Finland is home to over 230 game studios, including global household names such as Rovio, Supercell, RedLynx and Housemarque. They employ over 4,100 people, 30 percent of whom are foreign employees. In 2022, the Finnish gaming industry’s turnover was 3.2 billion euros.

(Source: Neogames, 2023) |

By Johanna Teelahti, ThisisFINLAND Magazine, February 2025