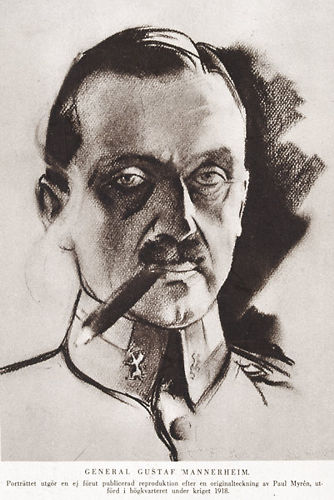

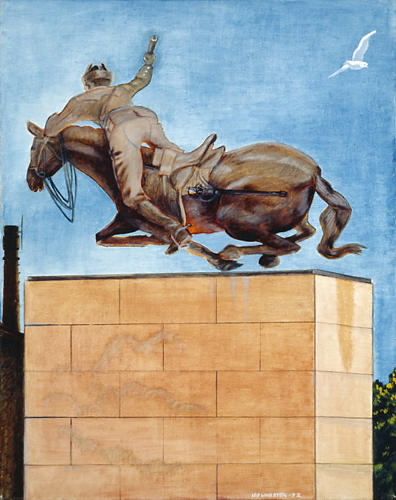

C.G.E. Mannerheim (1867–1951) charted the course of Finnish history and was voted greatest Finn of all time.

He served in the Russian Imperial Army for decades, and later became a war hero in his home country of Finland. He was the symbol of the Finnish struggle against Soviet Russia during the Winter War of 1939–1940. He was hailed as a champion of liberty throughout the Western world during those 105 days of stubborn resistance against a vastly superior enemy.

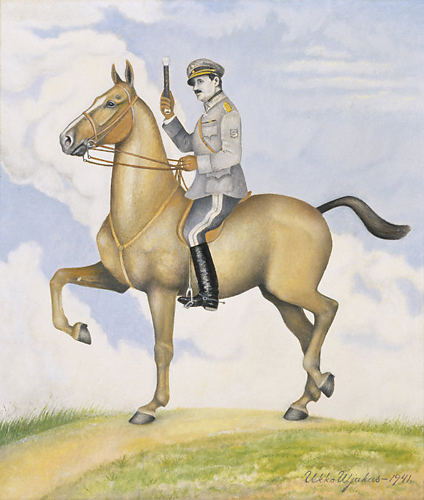

Colonel Mannerheim in his parade uniform as commander of the 13th Vladimir Regiment of Uhlans at Novo Minsk in 1909.Photo: Mannerheim Museum

This was not the first time that the stately representative of Finland’s Swedish-speaking aristocracy had been supreme commander in a war against Russia.

The War of Liberation in 1918 – later also called the Civil War – had been fought against Soviet Russia and against its allies, the Finnish “Reds.” And the Winter War was not the last war Mannerheim fought against Russia, either.

The period of combat known as the Continuation War, 1941 to 1944, during which German forces fought alongside the Finnish army, exacted a much heavier toll on Finland and Russia than the Winter War had.

Moreover, during the Continuation War, Finnish forces even advanced into Russian territory with the intention of annexing Eastern Karelia, a region which had never belonged to Finland.

Admittedly, Finnish policy towards the Russians and Finland’s methods of warfare substantially differed from those of the Germans. Finland declined to launch a ground attack or a bombing attack on Leningrad, despite German pressure to do so.

Remarkable career in Russia

Colonel Mannerheim in his parade uniform as commander of the 13th Vladimir Regiment of Uhlans at Novo Minsk in 1909.Photo: Mannerheim Museum

Mannerheim spent no less than 30 years in Russia, mostly in Saint Petersburg, serving in the Russian Imperial Army.

During this period he not only reached the rank of lieutenant general and was appointed commander of the Cavalry Corps of the Imperial Army, he was also known personally to the emperor and became a member of his suite.

The commander-in-chief with his generals and staff at the Rajajoki (Border River) in August 1941, observing Leningrad and the fortress of Kronstadt. Rajajoki had been the border of Russia and Finland, or more precisely Russia and Sweden-Finland, since the Treaty of Schlüsselburg of 1323.Photo: Gunnar Strandell, SA-Kuva

Mannerheim’s record as a soldier was impressive. He fought for Russia on the battle front in both the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 and in the First World War between 1914 and 1917. General Mannerheim was decorated with the St George’s Cross for gallantry and was famous for his military skill and efficacy.

Mannerheim was also an able sportsman whose horsemanship won prizes. This was evidently one of the reasons why he was chosen for the formidable task of undertaking a reconnaissance mission, on horseback through Asia, that lasted two years.

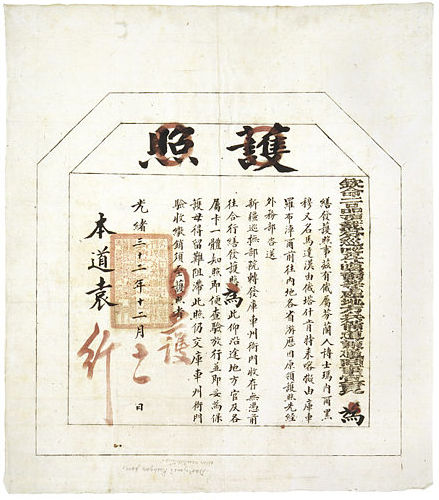

Mannerheim’s passport: “Order of the Imperially appointed minister to grant a passport. The Russian consul has stated that this man will come from the Russian-Chinese border to Xinjiang to visit certain localities and to see old monuments. He is to be given a passport and allowed to visit the places that he desires, and in addition he is to be protected. Given as a certificate to the Russian authorities. On the 27th day of the fourth month of the 32nd year of the reign of (Emperor) Guangxu (1906).”Photo: National Board of Antiquities

You could add courteous manners to the list of Mannerheim’s merits. This contributed to the progress of the young cavalry officer in high society and at the imperial court itself.

A non-Russian officer in the Imperial Army was no rarity. In fact, there were thousands of them. Many of these inorodtsy or “non-orthodox” subjects of the emperor serving in the Russian army came from the Baltic provinces, spoke German as their mother tongue and were Lutheran by religion, as was Mannerheim.

Distinctive background

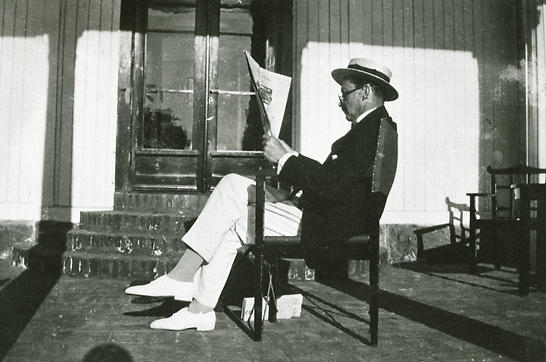

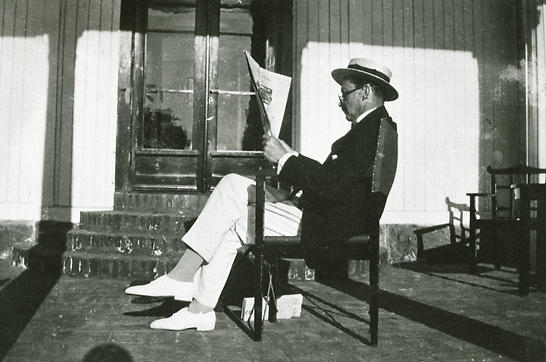

Mannerheim reads a newspaper on the porch of Stormhällan villa in 1926. In 1920, he rented Iso Mäntysaari, an island near Hanko in southwestern Finland. He later bought it and renamed it Stormhällan.Photo: Otava Publishers

However, Mannerheim’s background differed from that of his Baltic brother officers. He came from the Grand Duchy of Finland, which sent more than 4,000 officers to serve in the Russian army between 1809 and 1917. Almost 400 of them reached the rank of general or admiral.

Most of the officers from Finland spoke Swedish as their mother tongue, Finnish being used mainly as a second language, if they knew it at all. Mannerheim’s Finnish before 1917 was far from fluent.

However, in common with the Baltic German officers, the Finnish officers served the emperor impeccably. In fact, there are no records of disloyalty among the Finns, even during the period from 1899 to 1917 when Russia began to pressure Finland by undermining its juridical status. In lieu of disloyalty, some of the officers chose to retire from active service.

Mannerheim did not retire. He remained a faithful soldier even though he privately deplored the emperor’s policies, which he regarded as unwise. Even when his own brother was exiled to Sweden, Mannerheim’s loyalty to the emperor remained unshaken. His relatives understood his position.

Loyalties redefined

Mannerheim reads a newspaper on the porch of Stormhällan villa in 1926. In 1920, he rented Iso Mäntysaari, an island near Hanko in southwestern Finland. He later bought it and renamed it Stormhällan.Photo: Otava Publishers

It was only when the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 crushed the old order that Mannerheim realised his ties of loyalty to Russia had been cut. After the revolution he became a champion of the White Finnish cause.

His loyalty towards his native land was now total and he always respected its democratic institutions even though he was hardly a true democrat by conviction.

Mannerheim’s career in the service of two states is an intriguing story that excites curiosity. To Russians, Mannerheim is above all the cultivated young officer of the Chevalier Guards who stood by Nicholas II during coronation procession.

In Finnish eyes Mannerheim stands tall as the elderly marshal, a man of honour and a fatherly figure whose moral integrity and intelligence could always be trusted.

The author is a Finnish historian and professor emeritus of Russian Studies at the University of Helsinki.