More than two centuries after his birth, Johan Vilhelm Snellman remains one of the most influential architects of Finnish society. Philosopher, scholar, journalist and politician, he came to acquire towering importance for the genesis of Finnish literature, and, ultimately, Finnish national identity.

Johan Vilhelm Snellman was born on May 12, 1806 in Stockholm, Sweden, where his father was a sea captain. After the Russian takeover of Finland in 1808 and 1809, and the establishment of the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland, his family moved to the Finnish coastal town of Kokkola in 1813. When Snellman’s mother passed away only one year later, he was sent to school in Oulu, northern Finland, where his aunt lived.

Snellman matriculated from school at the age of 16. He then studied at the Academy of Turku, which was relocated to Helsinki in 1828 and became the Imperial University, and received his bachelor’s degree in 1831. During his studies, Snellman became friends with Elias Lönnrot and Johan Ludvig Runeberg, both of whom would have significant impact on his future endeavours.

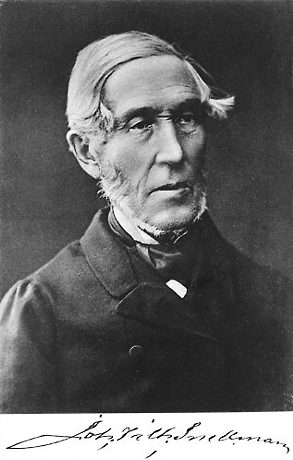

Fostering national consciousness

Snellman wanted to awaken Finnish national consciousness and stressed the importance of literature in promoting a sense of national identity.Photo: National Board of Antiquities

After finishing his doctoral thesis on Hegel, Snellman was appointed to the post of lecturer at the Imperial University in 1835. As an ardent opponent of Russian rule over Finland, he refused to take orders from the Russian-influenced university directorate on what and how to teach. Eventually, despite being highly popular among students, Snellman was temporarily suspended, in 1838, after a judicial action aimed at increasing the government’s control over dissent among academic personnel.

Consequently, Snellman voluntarily exiled himself to Sweden and Germany in 1839, and did not return to Finland until 1842. It was during these years that his ambitions in academic and political life began to crystallise: he wanted to awaken Finnish national consciousness.

In the mid-1800s, Swedish was the language spoken by the political and economic elite. Snellman believed that increasing the use of Finnish was a way for Finland to avoid assimilation by Russia. He stressed the importance of literature in promoting a sense of national identity.

Until the 19th century, however, there had been almost nothing published in Finnish apart from religious works. This void was eventually filled by the Kalevala, the Finnish folk epic and single most important work of Finnish literature. The book was compiled by Snellman’s friend Lönnrot. Another important publication was The Tales of Ensign Stål, a collection of poems authored by Runeberg. The first poem of the cycle, entitled Our Land, was soon set to music, and later became the national anthem of Finland.

Polemical periodicals

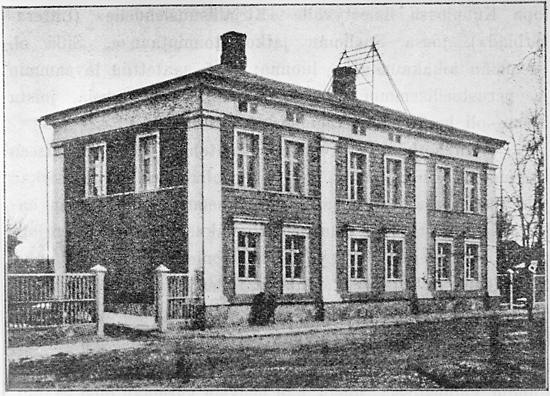

The school in Kuopio, eastern Finland, where Snellman taught.Photo: National Board of Antiquities

When Snellman returned to Helsinki, his popularity had increased further. Nevertheless, he quickly learned that his pro-Finnish opinions and aims did not please the Russian rulers. He was considered a radical extremist, and the political quandary prevented the university from employing him. Snellman thus moved to Kuopio, in eastern Finland, where he became headmaster of a school.

From Kuopio, Snellman began to publish two periodicals. Maamiehen ystävä (The Countryman’s Friend), the only newspaper published in Finnish at that time, was aimed at ordinary Finnish people, to strengthen their national identity and enhance their language skills. The other, Saima, written in Swedish, emphasised the duty of the educated classes to take up Finnish, spoken by 80 percent of the population at that time, and develop it into a language that could be used in academic work, fine arts, statecraft and nation-building.

Saima was regarded as highly controversial, especially by the targets of its criticism, and the government ultimately banned it in 1846. The views expressed in the paper nevertheless remained in public discourse, and Snellman received wide support for his views.

In 1849 Snellman returned to Helsinki, where he was again rejected, this time for a professorship at the University, leaving him and his family in economic hardship until the death of Emperor Nicholas of Russia in 1855.

Man of power

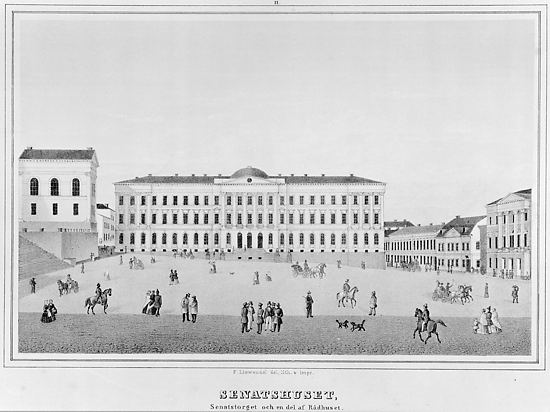

The Senate Building in Helsinki in 1851 (half-tone lithograph, F. Liewendal).Photo: Harald Malmgren/National Board of Antiquities

In 1856, Snellman was, to the great satisfaction of politically interested Finns, finally appointed professor. Seven years later, he was nominated for a cabinet post in the Senate of Finland, in effect as the Minister for Finance. As a senator, Snellman was able to pass a language decree that gradually gave Finnish a position equal to that of Swedish within the Finnish government, and thus effectively in the entire country. Moreover, Finland’s own currency, the markka, was introduced in 1865 mainly as a result of Snellman’s efforts.

However, Snellman, now a man of the government, was not able to retain his unparalleled popularity among all Finns. His uncompromising stand on the language issue also contributed to considerable opposition against him. Ultimately, Snellman’s inflexibility and position in the political debate, together with his old reputation as a radical agitator, accumulated too much resistance and antagonism against his person and policies. He was forced to resign from the Senate in 1868.

Eminent statesman

Despite his setbacks, Snellman continued to participate in political debate for the remainder of his life. He was made a nobleman in 1866 and thus acquired a seat in the Nobles’ Chamber in Parliament. Even though Snellman never lost his popularity among his pro-Finnish adherents, he had developed into a highly divisive figure in Finland’s political landscape.

Snellman died in July 1881. His statue stands in front of the Bank of Finland and his picture has appeared on Finnish banknotes. Given his colossal significance in Finnish nation-building, Johan Vilhelm Snellman is regarded by some as the greatest statesman in the country’s history.

By Otto Utti, January 2006